For years, a hardcore group of U.S. national security hawks have warned about the threat of electromagnetic pulse weapons that could wipe out satellite communications, take down the electrical grid, and create what one nuclear physicist called a “continental-scale time machine.” Those fears have been revived in recent weeks amid an escalating war of words with North Korea, yet no plan has emerged for dealing with the threat, according to those following the issue.

On Sept. 30, the Congressional Commission to Assess the Threat to the United States from Electromagnetic Pulse (EMP) Attack shut its doors after 16 years of operation.

Former Speaker of the House Newt Gingrich, R-Ga., who has been one of the most vocal proponents of taking the threat of EMP seriously, said he decided not to fight the commission’s closure after consulting experts. “People I trust who are very concerned [about the EMP threat] thought that we needed a fresh start,” he told Foreign Policy in an interview.

Concerns about EMP weapons date back to the 1962 Starfish Prime test, when a nuclear weapon detonated 250 miles above the Pacific knocked out street lights in Hawaii. Scientists realized nuclear weapons set off in the upper atmosphere released “killer” electrons that can fry electronics, which today would include satellites in low-Earth orbit.

Gingrich has repeatedly cautioned about EMPs, including in testimony before the Senate Committee on Energy and National Resources in May, and in a FoxNews.com editorial in June. The former speaker’s fascination with EMP led Michael Crowley in 2009 to mock it as the “Newt Bomb” in the New Republic.

While critics have long derided such fears as the stuff of tin foil hat conspiracy, last month, North Korea’s state news agency claimed the country had developed thermonuclear weapons specifically capable of detonating at high altitudes to create an electromagnetic pulse. The EMP commission shut its doors a few weeks later.

Though the administration’s “instinct is to take all this very seriously,” the slow pace of political appointments has made addressing EMP nearly impossible, according to Gingrich.

The Donald Trump administration has been notoriously slow to fill positions across government.

James Mattis, the Pentagon chief, has been forced “to make decisions that are three levels below the secretary of defense,” Gingrich said. “You don’t get much strategic planning when that’s what you’re doing.”

Still, Gingrich said that he is comforted that Department of Energy head Rick Perry is focused on national security. (Others may be less comforted by that; a New York Times article from January claimed Perry didn’t realize at first that his new role included stewardship of the country’s nuclear arsenal.)

Yet the commission’s closure is only the latest in a series of steps retreating from plans to protect against EMP. Since the end of the Cold War, the military has pulled back from hardening electronics against the effects of EMP, except for some specialized equipment, such as Air Force One.

In fact, the only Pentagon program looking at ways to mitigate the effects of an electromagnetic pulse weapon was shut down some eight years ago, according Dennis Papadopoulos, a professor of physics at the University of Maryland’s departments of physics and astronomy.

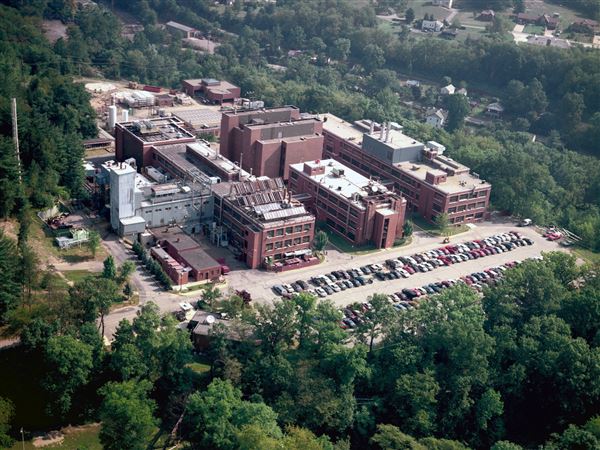

For several years during the George W. Bush administration, the Pentagon’s Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency had a program involving HAARP, an ionospheric research facility based in Alaska, to see if it was possible to clean up the killer electrons created by an EMP weapon. That experimental program was shut down around 2009, however.

Politics drove the Pentagon to close the program, Papadopoulos said. “It was ridiculous,” he told FP. “The excuse they used was ‘politically it might disturb Chinese if we find the solution to that problem.‘”

As for any new research programs looking to mitigate the effects of EMP, “there is nothing,” Papadopoulos said.

While some may worry about this neglect, others have long dismissed the threat of an EMP attack as unlikely.

The EMP commission “had plenty of time to make their case,” said Nick Schwellenbach, director of investigations at the Project on Government Oversight, a nonpartisan watchdog group. “Enough taxpayer dollars were spent on the commission.”

The Department of Energy’s national lab infrastructure and research labs at the Department of Defense should be able to address the issue in the commission’s absence, Schwellenbach argued.

While experts agree an electromagnetic pulse would be devastating in theory, scientists have argued for years about how difficult it would be to create a weapon that maximizes those effects. For Schwellenbach, fear of such a hypothetical attack “rests upon a large number of sketchy assumptions.”

A major EMP attack would need specific conditions for success, according to Yousaf Butt, a physicist and a senior research fellow at National Defense University. An EMP bomb “needs to be detonated at a particular altitude,” he told FP, “It needs to be launched in a specific way.”

While the EMP commission is finished, its proponents aren’t giving up. In congressional testimony last week, the EMP commission’s former chief of staff, Peter Vincent Pry, urged lawmakers to take the threat seriously, repeating an earlier warning that an attack that took down the U.S. electricity grid could kill 90 percent of Americans.

“North Korea has the capability to make an EMP attack. Right now,” he said.

The enemy dictatorship could launch an attack with a single weapon affecting all of North America, taking down electrical grids, transportation, and communications, he said.

Critics of the EMP commission point out that even if terrifying, such an attack from Pyongyang would be unlikely, because the United States would then retaliate with a nuclear attack against North Korea. “It’d be suicide to launch an EMP attack,” said Schwellenbach.

But that level of retaliation isn’t realistic to Gingrich. “We’d react with a direct nuclear weapon?” he said. “That’s a pretty big escalation.”

While some experts have questioned the likelihood of a North Korean EMP attack, arguing the concern should be a solar storm that could wreak similar devastation on the electrical grid. Steps to harden the electrical grid and other vulnerable infrastructure against a solar storm would also help protect against an EMP attack.

North Korea “is just inherently unpredictable,” said Butt, the physicist. However, “if you want to worry about something, you should worry about the sun.”

First Published: October 17, 2017, 2:15 p.m.