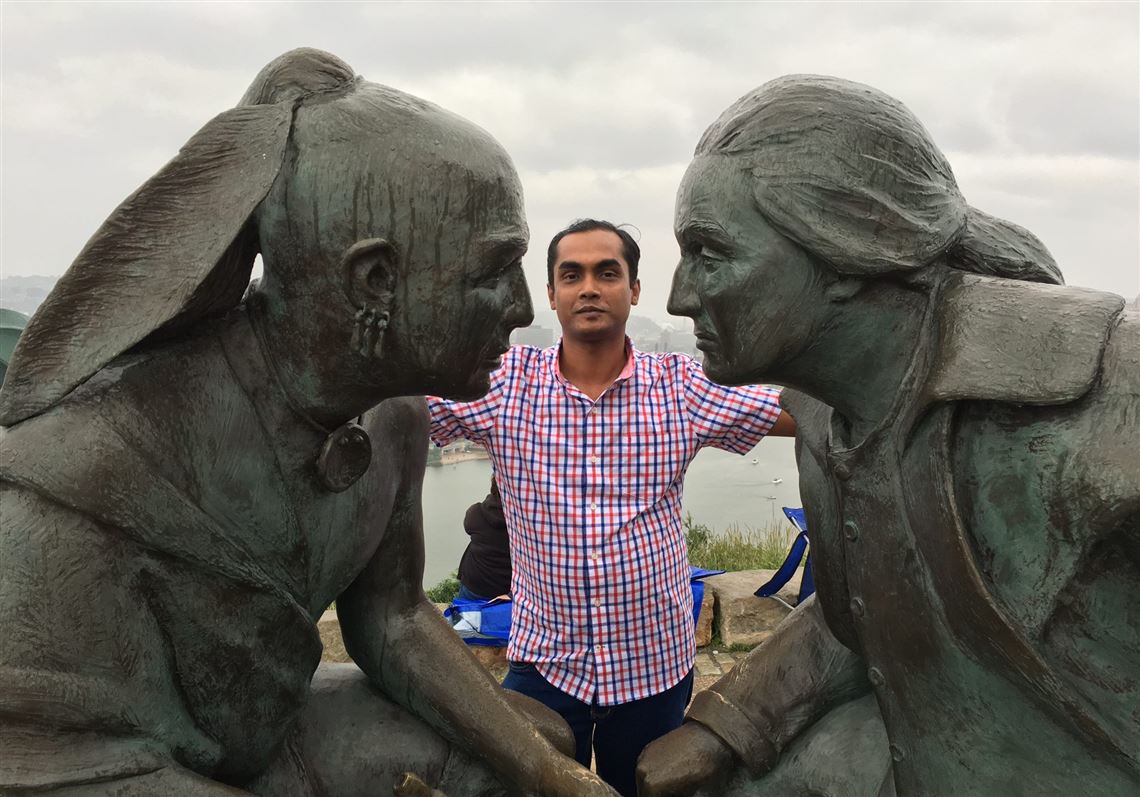

In 2015, al-Qaeda issued death threats against me in my home country because of my writings about religious persecution. I was raised in a Hindu family in Bangladesh, which is a majority Muslim country. I decided to leave in order to live.

Due to security precautions, I lived in hiding for many months in different cities. My father was able to come to Dhaka, the capital city, in order to see me off at the airport, but I was unable to say goodbye to the rest of my family in person. On the morning of my departure my father’s glasses broke, leaving him unable to see clearly. I was concerned about him accompanying me without his glasses, but he said he wanted to be beside me when I was leaving the country, so I called a friend who is a painter and left my father in his care. My friend gave me a farewell gift he painted, which I have hanging in my study room here in Pittsburgh.

I left Bangladesh in April 2016 with $300 (U.S.) in my pocket. On my way from Bangladesh to Pittsburgh, I transferred through four airports. I was thirsty waiting at Chicago O’Hare, so I spent $3.50 to buy an orange drink; I was shocked at the high expense because this would have cost about 20 cents in my hometown. I was afraid of running out of money, though I knew in Pittsburgh there were good people waiting for me.

I had been invited by Carnegie Mellon University to be a short-term scholar in the english department’s creative writing program. I had also been invited to join the writer-in-residence program with Pittsburgh-based nonprofit City of Asylum. That fall, I applied for asylum with the U.S. government because I was afraid to go back home. I knew more writers had been murdered by Islamic fanatics since I had left, adding to the dozens who had already become victims of al-Qaeda.

Prior to the 2016 presidential election, I asked a colleague, “Who will win? Hillary Clinton or Trump?” She replied, “She will be first woman American president. We are seeing history in the making.” On Election Day, I watched TV with a bunch of people because I was told this was something Americans do. In the middle of the night, their faces became discolored as they were drinking more and getting upset. I then understood Hillary Clinton would lose. I walked home and went to bed.

The next morning, I woke in a new America. In the days that followed, everywhere I went — a jazz club, a bar, a restaurant, a bookstore, a church — people offered me safe shelter. One person offered to put me up in a summer house; another gave me a paper with instructions about what to do if Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) came to find me. I became anxious. I had come to this country legally, and I was inspected by an immigration officer, but their concerns caused me to worry, so I limited my social activities.

In 2017, I gave my asylum interview and submitted all the necessary paperwork. I waited for the result. 2018 and 2019 passed. I wanted to see progress, but nothing was happening. No matter what I tried to do, people asked me to remain patient. I kept busy with writing, editing, publishing and presenting my life story in universities, schools, theaters and galleries.

In March 2020, I was invited to read my poetry at a writer’s conference in San Antonio. The night before my flight, I felt nervous about going after learning about a cruise ship in Texas with passengers infected with COVID-19. I decided not to go. Soon after, we were notified the pandemic had arrived.

Prior to this, I had been doing great in America, improving my English, making friends and gaining job experience. Suddenly, I felt trapped. Life came to a standstill during the pandemic. We all experienced isolation during this time, but for me, it seriously intensified my feelings of exile. I was nervous about getting sick, but I had to work to pay my bills and to support my family back home. Also, I was drinking and smoking a lot. I couldn’t stop.

I distracted myself by collecting Bangladeshi stamps from sellers from all over the world; I became a philatelist. At first, I was afraid of catching the disease from the paper, but this went away. This pastime calmed me down; collecting these stamps became a physical connection to my homeland, allowing me to have something tangible that belongs to Bangladesh. I also began doing simple pen drawings of shapes, bodies, birds and other animals. These surrealistic drawings are a form of therapy for me that enables me to express myself when the words do not come.

In early 2021, I reached out to my attorney about the progress with my asylum case, but complications due to the pandemic delayed the process. This felt like an eternity. I was sad, exhausted and in despair. It was difficult to concentrate on writing. I know a writer from my hometown who has been living in America for 15 years and still has not received asylum. I was not prepared to face this kind of fate.

Then, just before Thanksgiving, I received my gift from America: I learned that I was granted asylum! I appreciate all the support I have received from so many people and organizations, including City of Asylum, Literacy Pittsburgh, Jewish Family and Children Services and All for All. I will close by sharing a poem that will be included in my forthcoming book of poetry:

In exile I often cannot sleep,

I remember my homeland.

On those still-dark dawns

I would walk along the alleyways

of the city down to the river.

Dangling from a corner of the sky,

the clouds would smile at me.

I used to think there was

a distant country beyond those clouds.

That’s where I’ve arrived today.

Telling myself, if only my eyesight

could go a little farther,

perhaps I would see

my unforgotten country once again!

Tuhin Das is a writer-in-residence at City of Asylum in Pittsburgh.

First Published: January 23, 2022, 11:00 a.m.