This year above all, our Independence Day commemorations and introspection ought not to conclude on the Fourth of July. Indeed, in a year like this — in our national moment of reflection and rebellion — we require one more day of contemplation on our national character and our national purpose.

This year, we should not conclude our national self-assessments on July 4.

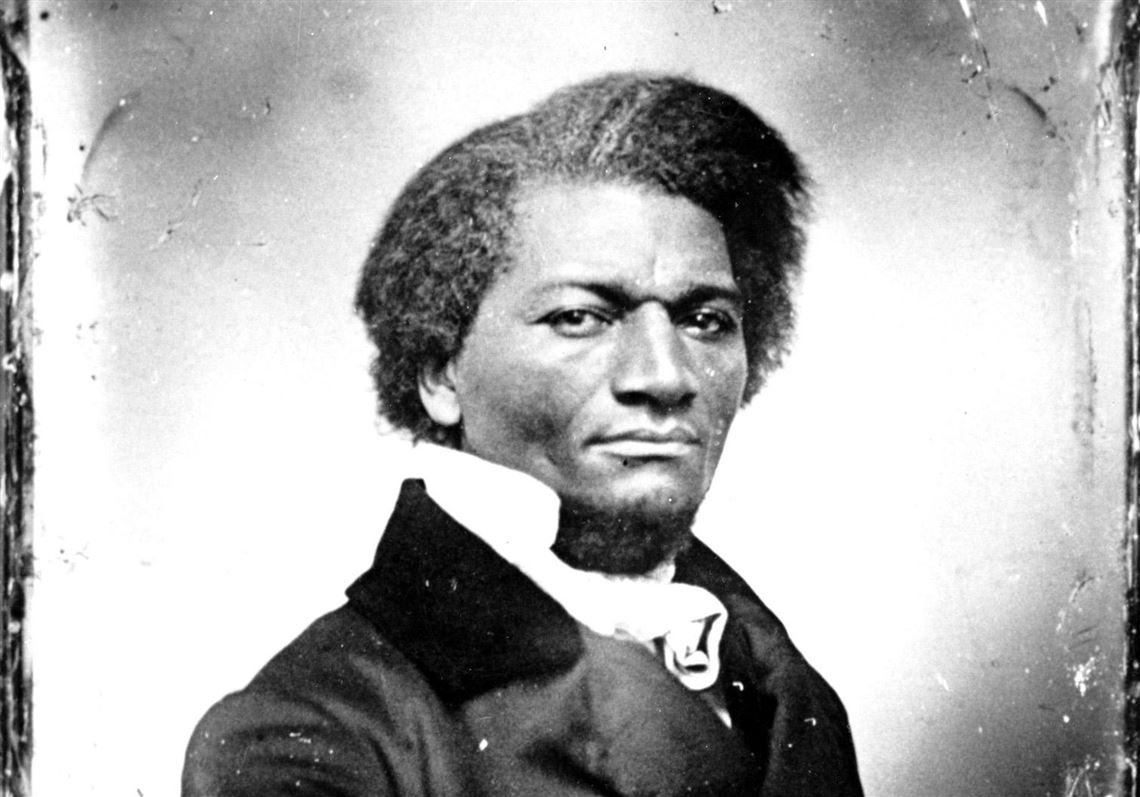

This year, let us lengthen our observations to July 5, and not to prolong our holiday merriment but instead to extend our holiday meditations. We should do so because 168 years ago, on July 5, 1852, Frederick Douglass delivered an Independence Day speech in Corinthian Hall in Rochester, New York. The great abolitionist, perhaps the preeminent orator in American history, vowed never to celebrate Independence Day on July 4 until the enslaved were freed.

And so, in 10,496 remarkable words in a speech that bears as its title his searing question “What to the Slave is the Fourth of July?” — Douglass spoke about the American Constitution and the American conscience. Here are some excerpts that resonate in our time:

The papers and placards say, that I am to deliver a 4th July oration ... The fact is, ladies and gentlemen, the distance between this platform and the slave plantation, from which I escaped, is considerable — and the difficulties to be overcome in getting from the latter to the former, are by no means slight. That I am here today, is, to me, a matter of astonishment as well as of gratitude.

In this passage, Douglass speaks of his own escape from enslavement and converts it into an American passage. He often remarked upon that great journey, and he employed it as a metaphor for the American journey — a road a later American voice might describe as a road not taken, yet.

This ... is the birthday of your National Independence, and of your political freedom. ... This celebration also marks the beginning of another year of your national life; and reminds you that the Republic of America is now 76 years old. I am glad, fellow-citizens, that your nation is so young ... There is hope in the thought ... May (I) not hope that high lessons of wisdom, of justice and of truth, will yet give direction to her destiny?

We sometimes think of America as young in the family of nations, but in 1852, it was truly young. It had begun its national life with much growing up to do, but with great promise. Here Douglass beseeches America to realize that promise, and its potential.

(T)he Declaration of Independence is the ring-bolt to the chain of your nation's destiny. ... Stand by those principles, be true to them on all occasions, in all places, against all foes, and at whatever cost. ... Your fathers have lived, died, and have done their work, and have done much of it well. You live and must die, and you must do your work.

In this passage, Douglass reminds Americans of the virtues the nation spoke of in its birth and bids it to listen to its own voice.

What have I, or those I represent, to do with your national independence? Are the great principles of political freedom and of natural justice, embodied in that Declaration of Independence, extended to us? ... I am not included within the pale of this glorious anniversary!

Here Douglass traces what he called “the immeasurable distance between us” and suggests the immeasurable distance America must travel to extend its high moral purpose to those who have been deprived of its gifts.

The blessings in which you, this day, rejoice, are not enjoyed in common. The rich inheritance of justice, liberty, prosperity and independence, bequeathed by your fathers, is shared by you, not by me. The sunlight that brought life and healing to you, has brought stripes and death to me. This Fourth July is yours, not mine. You may rejoice, I must mourn. To drag a man in fetters into the grand illuminated temple of liberty, and call upon him to join you in joyous anthems, were inhuman mockery and sacrilegious irony. Do you mean, citizens, to mock me, by asking me to speak today?

This speech was delivered two years after the Compromise of 1850, nine years before the outbreak of the Civil War and 11 before the Emancipation Proclamation. The Dred Scott decision asserting Blacks were not citizens was five years away. The tinder of the great reckoning with human bondage had been laid.

Fellow-citizens; above your national, tumultuous joy, I hear the mournful wail of millions! whose chains, heavy and grievous yesterday, are, today, rendered more intolerable by the jubilee shouts that reach them. If I do forget, if I do not faithfully remember those bleeding children of sorrow this day, "may my right hand forget her cunning, and may my tongue cleave to the roof of my mouth!"

By invoking Psalm 137 and pairing it with the "mournful wail of millions," Douglass elevates the slavery question from the politics and the economics of the day to an enduring principle enshrined in the Bible. David Stowe, a Michigan State University professor of English and religious studies, said this passage, referring to the Babylonian exile when the ancient Jews were held captive, had “long served as an uplifting historical analogy for a variety of oppressed and subjugated groups, including African Americans." One of those who employed this psalm — which opens “By the rivers of Babylon, there we sat down, yea, we wept” — was C.L. Franklin, the father of the singer Aretha Franklin.

I do not hesitate to declare, with all my soul, that the character and conduct of this nation never looked blacker to me than on this 4th of July! Whether we turn to the declarations of the past, or to the professions of the present, the conduct of the nation seems equally hideous and revolting. America is false to the past, false to the present, and solemnly binds herself to be false to the future.

These words might be uttered this weekend by those who, in Douglass’ words, are left “crushed and bleeding" in our time. The anti-slavery newspaper Douglass published from Rochester was called The North Star. Americans of all races have a North Star from which to navigate our national passage. That North Star is the Declaration of Independence, issued 244 years and one day from July 5, 2020.

David M. Shribman is executive editor emeritus of the Post-Gazette and a nationally syndicated columnist. He is scholar-in-residence at Carnegie Mellon University (dshribman@post-gazette.com).

First Published: July 5, 2020, 8:15 a.m.