There is nothing older than yesterday’s newspaper.

That’s an old saying in more than one language, but there is something even older: a government report. Generally, they get churned out only so politicians have something for their shelves. They don’t want their offices looking barren. That could screw up the next photo op.

So I was stunned when Chris Zurawsky of Squirrel Hill told me he’d gone to the Pennsylvania Room of the Carnegie Library of Pittsburgh to find the city’s 2001 master development plan for Hazelwood and Junction Hollow. I mean who does that?

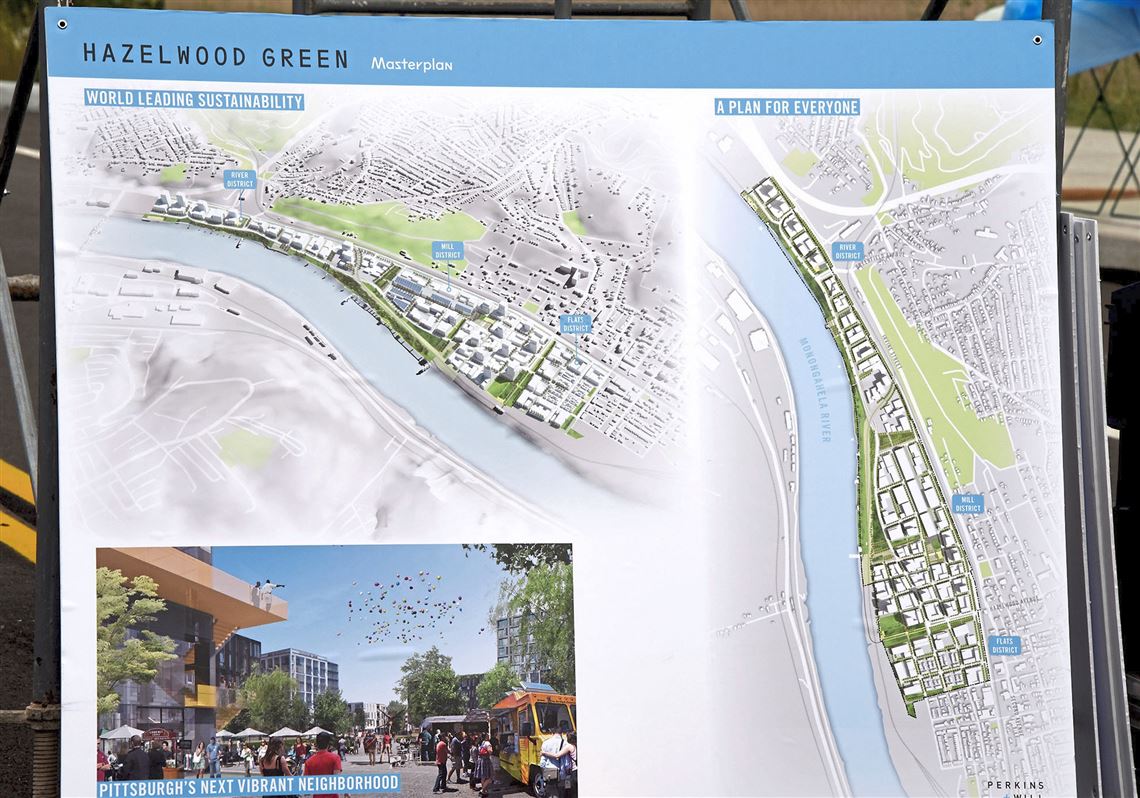

Mr. Zurawsky, vice president of the Squirrel Hill Urban Coalition, was seeking historic context for ongoing arguments about a driverless shuttle service planned for the roughly two-mile stretch between the Oakland campuses and the sprawling Hazelwood Green development. That’s where Uber has a test track.

I’d written last Sunday that this story has taken plenty of twists and turns these past couple of years, and Mr. Zurawsky suggested I ride that hypothetical road back further. In 2001, participants in a day-long workshop unanimously endorsed the idea of using light rail to connect the Hazelwood site to Oakland, following the railroad line that’s already running eight trains a day.

Participants unanimously rejected a new full-access roadway, even if it had a strong pedestrian element, but unanimously supported a busway. Then, as now, there should be “a desire to retain the tranquil setting in the hollow” and improve connections to Schenley Park.

Now here’s the funny quote in the study: “This process has ensured [emphasis mine] ... that the kinds of development and transit connections being considered will be sensitive to the quiet natural setting of the neighborhoods in and near Junction Hollow, including Boundary Street and Four Mile Run.”

Nothing is ever ensured by a non-binding report. Residents of Four Mile Run, the quiet slice of Greenfield astride the planned route, know that and so do those living in even smaller and quieter Panther Hollow.

Let me pause here to address those readers who inevitably tell me I should be calling that latter neighborhood “Junction Hollow,” despite what residents have called their neighborhood for more than a century. These critics and their official maps remind me of an old copy editor who once insisted we say that Central Catholic is in Squirrel Hill because he had a city neighborhood map showing that Fifth Avenue was Squirrel Hill’s northern border.

He backed down only after I suggested he call an assembly to inform all Central students and faculty they’d been taking the wrong bus. Neighborhood boundaries are the most democratic on Earth, so if residents of a hollow say it’s Panther, it is.

Anyway, Jackson/Clark Partners, hired by the Greenfield Community Association with funding from Heinz Endowments, surveyed residents of Four Mile Run last year and found a stable community, largely made up of homeowners who like where they live and don’t want to move. But at that point, they mostly hadn’t felt as if the city was addressing their concerns. Some 27 percent of respondents reported flooding in their homes and 13 percent had persistent mold.

Their priority isn’t this shuttle service, even if it would be free. It’s that 37 of respondents had sewage in their basement and flooding their yards, and it generally happened more than once.

The city is paying attention now, both to the flooding and the residents’ desire for minimal impact from the proposed shuttle. A smart card or app so only residents and nobody else could board the shuttle in Four Mile Run is one potential outcome. Maybe that won’t come to pass, but the Peduto administration clearly is listening.

For such a seemingly quiet part of town, the Run, as it’s commonly known, is pretty good at punching above its weight. Sol Gross, 95, called last week to remind he once owned 28 acres just outside the neighborhood. He parked cars there until the city revoked his permits, while it also blocked Mr. Gross’ plans to build student housing. When the dust cleared in 2000 after a decade-plus legal battle, Mr. Gross was awarded $14 million for his land, and the city was able to put in what must be the world’s most expensive youth soccer field.

Some stories never get old.

Brian O’Neill: boneill@post-gazette.com or 412-263-1947 or Twitter @brotheroneill

First Published: March 11, 2018, 11:00 a.m.