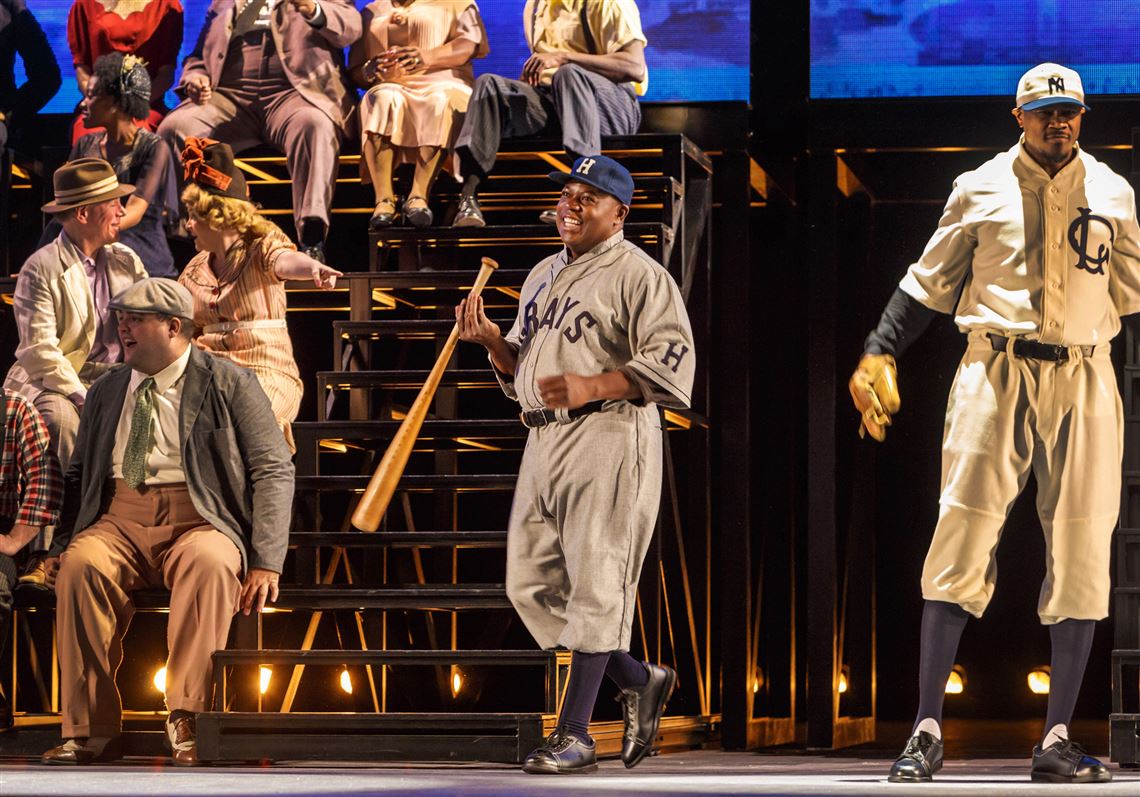

Josh Gibson, the greatest slugger of his day, who was denied the chance to play on baseball’s biggest stage, has arrived at long last in a forum worthy of his epic story.

I was among the Benedum Center crowd that rose to its feet at the conclusion of Pittsburgh Opera’s performance Tuesday of “The Summer King,” having been swept up by the sound and spectacle. Opera is not generally an art form I find easily accessible, but this plot hinged not on tuberculosis in 19th-century Paris or a hunchbacked jester in 16th-century Italy.

This was about athletic greatness and moral skimpiness in 20th-century America. I was hooked from the opening scene in a 1950s Brooklyn barbershop to its tragic ending in Pittsburgh. This is the opera company’s first world premiere in its 78-year history, and the performers knocked it out of the park.

On the long walk home, I wondered how much of an impact this production was having in the small fraternity of American opera composers — and I knew just who to call.

“It’s a very big deal,” Tommy Cipullo said.

Actually, he’s Tom Cipullo now, and his opera, “Glory Denied,” about America’s longest-held prisoner of war, has been staged from Anchorage to New York City. But we met in Cherry Lane Elementary School in suburban Long Island and graduated high school together 43 years ago. He was Tommy Cipulllo since I knew him and so “Tom’’ will take some getting used to.

Turns out Mr. Cipullo (which is even harder to type) knows Daniel Sonenberg, who composed “The Summer King,” and knew this opera to be more than a decade in the making.

“It was a great piece from the beginning, and it’s so different,” Mr. Cipullo said. “You can work for years [on an opera] and get no payoff, not financial and not emotional. Now it’s on the fast track to a great success and, hopefully, entering the repertoire.”

I reached Mr. Sonenberg Wednesday afternoon at LaGuardia Airport, where he was changing planes with his 8-year-old triplet sons en route from their home in Portland, Maine, to Pittsburgh. It was the boys’ first flight, so he had his hands full but was gracious enough to share what he could.

Some of the music in “The Summer King” goes back to 2003, so to finally see a full production “is very, very intense,” he said. “I had never heard singers of this level sing through the opera.’’

He loved that set designer Andrew Lieberman and director Sam Helfrich had conceived of using bleachers as the backdrop pretty much throughout the production. That conveyed the sense “that Josh’s life is trapped in this ballfield.”

Mr. Sonenberg, also from Long Island, said he grew up a Yankees fan and a history buff, and he was interested in Josh Gibson’s story long before he had any interest in opera. This giant of the Negro Leagues played a grueling schedule for the Pittsburgh Crawfords and Homestead Grays, but it was a game the man loved, and Mr. Sonenberg believes opera to be the only medium large enough to do justice to “a story of American heroism.”

Long before the curtain came down, I was persuaded. Unfamiliar singers shared voices that sat me up in my chair. To use that old ballfield cliche, they left it all on the field. The program listed past credits that stretched out like the PNC Park foul lines, but lending their pipes to such an epic American, and particularly African-American, story had to be a rare chance.

“There aren’t enough certainly,” when I asked Mr. Cipullo what other operas besides “Porgy and Bess” had many African-American roles. But he said casting has gotten more blessedly colorblind and opera companies have come around to composers exploring contemporary themes.

“As an art form,” Mr. Cipullo said, “opera is the dumbest thing in the world. You have to suspend disbelief to a crazy degree. But when it’s good, there’s absolutely nothing like it for communicating with people. It’s really the most fun thing you can do.”

His dad had been a jazz bass player and his brother a rock drummer, so “my teenage rebellion was being stodgy and going into classical music.” His opera “Glory Denied,’’ about Col. F. James Thompson, who spent nine years as a Vietnam prisoner of war and came home to a country he no longer recognized, was staged in Nashville in November, where Mr. Cipullo met the late colonel’s four children.

Mr. Sonenberg has gotten to know Sean Gibson, Josh’s great-grandson and executive director of the Josh Gibson Foundation, in writing this opera. Mr. Gibson has been to every performance.

The student matinee today is sold out but there are also shows at 7:30 p.m. Friday and 3 p.m. Sunday, with tickets as low as $12. The last show will be followed by a celebrity-studded reception at the August Wilson Center. (Reservations for the $150 reception only can be made by calling 412.589.1906 or at www.joshgibson.org.)

Seventy years after his untimely death, Josh Gibson has reached center stage.

Brian O’Neill: boneill@post-gazette.com or 412-263-1947 or Twitter @brotheroneill

First Published: May 4, 2017, 4:29 a.m.