“There’s no lead in our water.’’

You can’t be clearer than James Good, executive director of the Pittsburgh Water and Sewer Authority, when I pressed him after some statistics last week left me wondering.

What he meant, though, was there is no lead in the PWSA’s source water or the 930 miles of main lines. What might happen between those lines and the customer’s tap can be a different story.

With more than half the homes in the city at least 75 years old, and many blocks of homes built in the 19th century, I can’t be the only one curious about what exactly is spewing from ancient plumbing.

Tests by the PWSA three years ago, largely targeted at those older homes most likely to leach lead, found that five of the 50 homes had lead levels of 14.7 parts per billion or higher.

That’s well below what was found in Flint, Mich., where 10 percent of the homes tested had levels of 27 parts per billion or higher, and at least one had a reading of 397 ppb.

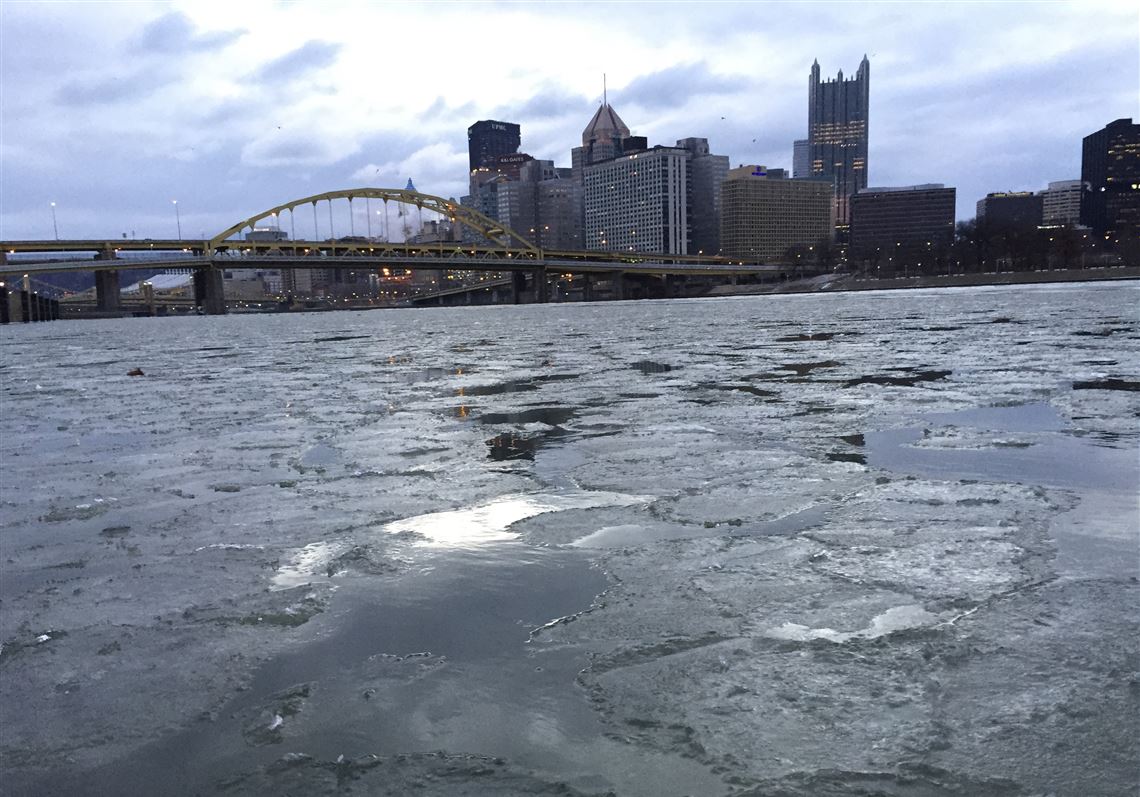

The Allegheny River, from which the PWSA gets its water, is not the foul stream the Flint River is. But 14.7 parts per billion is nonetheless uncomfortably close to the federal Environmental Protection Agency’s “Action Level” of 15. If that lead level is surpassed when the PWSA initiates its next series of required tests between June 1 and Sept. 30 this year, the feds would require annual testing and notification of affected customers.

Why wait for those tests? The PWSA stands ready to test its customers’ water free of charge. Now.

I called the number — 412-782-7554 — Wednesday afternoon, identifying myself only as a customer, not a newspaper columnist. I got straight through. A lab worker took my name, address and phone number, promising to mail me a couple of bottles that I could put under my cold-water tap. I could then contact the PWSA to set up a time for pickup of those samples for testing.

The authority will do that for any customer.

In the meantime, the PWSA began using a chemical last week that should make the water less corrosive and form a film within all these household pipes to prevent lead from leaching into the water. It’s a switch from soda water to soda ash and, if it’s successful, it should result in better readings when tests commence in June.

I’ve long considered the purchase of bottled water one of the great unnecessary expenses of our time. I drink tap water at home, in restaurants and at work. Those who would rather pay much more for water that has been carried in a plastic bottle through all kinds of temperatures — I’ve never been entirely sure why that’s a better bet.

The new numbers do give me pause, though. The PWSA had the highest lead level readings of any of the public water suppliers in Allegheny County. Some of that can be attributed to a higher percentage of older homes, but Braddock has old homes, too, and its reading at the critical 90th percentile was less than a third of the PWSA’s.

Mr. Good said 75 percent of the tested PWSA homes were under 5 parts lead per billion. More than half were around a half-part per billion, “trace level.’’ The PWSA has used additives to limit the corrosivity of its water at least since 1991, he said, and water quality “is job No. 1 for us.’’

So it’s doing a little more. And I expect some readers of this column, if they’re concerned enough to have read this far, will also be concerned enough to make a call for a free test — particularly if they live in a house older than “The Wizard of Oz.’’

The test is free, but freeing the pipes of lead won’t be. That could cost a homeowner thousands of dollars. Still, it’s better to know what you and your family are drinking, and I’m told the PWSA has contracted with an outside lab in the event there’s a huge spike in calls.

I left its offices with one of its “PGH2O’’ bottles. The label says the water was “purified by carbon filtration, UV light and ozonation.’’ It tasted good, maybe even a little better than what I’ve been drinking at home, but I hope I’m imagining that.

Brian O’Neill: boneill@post-gazette.com or 412-263-1947.

First Published: January 28, 2016, 5:00 a.m.