With the exciting news that the prestigious Danish architecture firm Bjarke Ingels Group has been hired to design parts of the former Civic Arena site, we think it is worth looking back at other famous architects who have presented design proposals for Pittsburgh.

Of special interest are those that never took wing. Some were large-scale visions conceived by the biggest names of the era. Had these proposals materialized, several neighborhoods, including Downtown, the Lower Hill and Oakland, would be unrecognizable today.

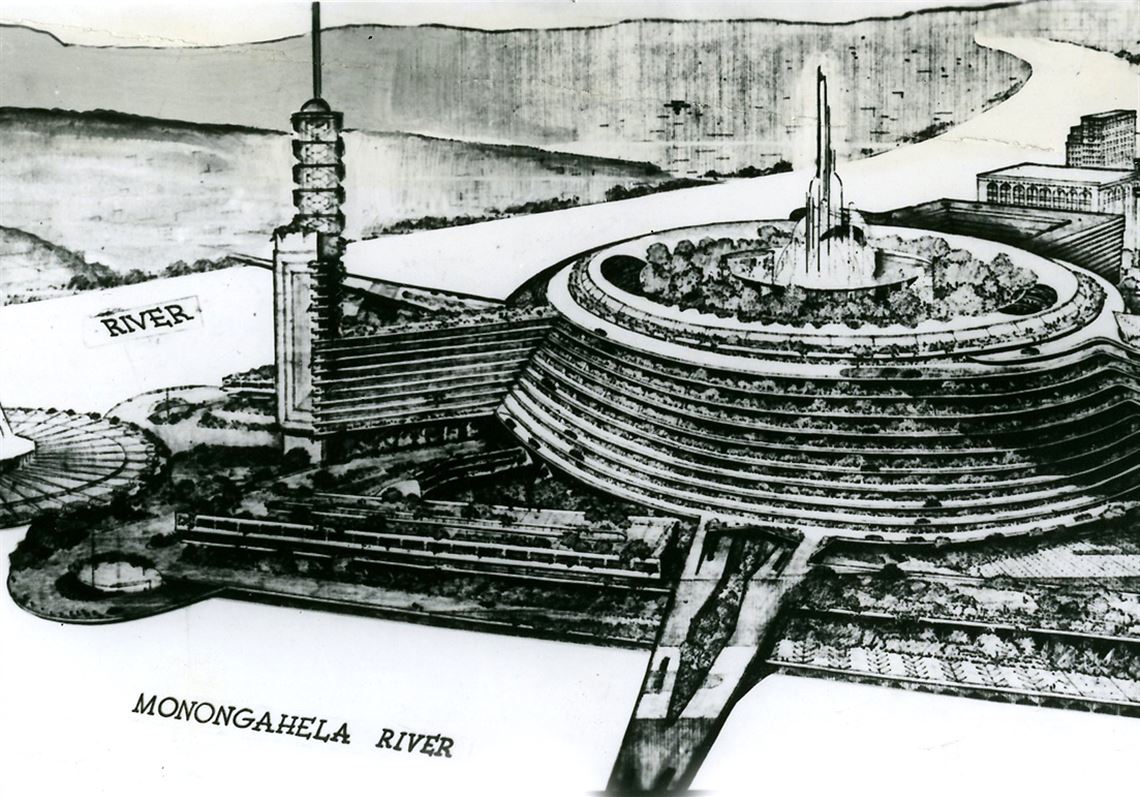

Frank Lloyd Wright and the Point Park Civic Center

Wright was behind two of the unrealized designs.

In the late 1940s, at the behest of businessman and booster Edgar Kaufmann, Pittsburgh approached the celebrated architect to design a civic center complex at the Point. It was to have an urban feel, but Wright was supposed to minimize vehicular congestion and restore the French and Indian War-era fort that gave the city its name.

In characteristic form, Wright did neither, proposing instead an enormous corkscrew ramp, nearly a quarter-mile in diameter, that would provide access to a number of ambitious venues, including an opera house, planetarium, aquarium, exhibition halls and a sports arena. The complex was to be connected via two multi-level bridges to the North Side and the South Side, with a third connection leading to a 500-foot tower at the confluence of the three rivers.

Following a muted reaction from the Point Park Committee, Wright proposed a second, slightly more subdued version: two cable bridges hanging from a 100-foot tower. The mammoth ramp remained in the plan as a parking podium.

Failing to gain traction, the project was shelved in favor of Charles Stotz’s landscape proposal and the modernist towers of Gateway Center.

SOM and the Pittsburgh Center for the Arts

Building on the success of Gateway Center and other Downtown projects, Pittsburgh’s civic leaders set their sights on the renewal of the Lower Hill.

In an attempt to redefine it as the city’s “cultural Acropolis,” land was cleared for construction, displacing thousands of largely African-American residents and hundreds of businesses. The Civic Arena was the first project built on the site, and it was to be followed by a Center for the Arts with a museum of art (relocated from Oakland) and a new symphony hall (supported by an $8 million grant from the Howard Heinz Endowment).

In 1961, Skidmore, Owings & Merrill was hired to design the project. The firm’s team was led by Gordon Bunshaft, known for the Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library at Yale University; 1 Chase Manhattan Plaza, now 28 Liberty, in New York; the elegant Point State Park portal bridge; and H.J. Heinz Co’s Vinegar Plant and Warehouse on the North Side, among other projects.

Bunshaft addressed the sloping site by designing an enormous plinth with the art museum and the symphony hall at opposite ends of a landscaped plaza, affording dramatic views. The symphony hall was to be wrapped in a monumental glass box and flanked by oversize travertine columns supporting a waffle-slab roof. The three-story art museum was to be enlivened with a crenelated roof structure.

However, within a few years, the coalition formed to support the project fell apart in the face of opposition by Hill residents, who grew increasingly suspicious of the project, and by Oakland institutions that did not want to see the art museum relocated. H.J. Heinz II invested in a Downtown symphony venue, the art museum remained in Oakland and the Hill waited decades for additional development.

Harrison & Abramovitz and Panther Hollow

In the 1960s, Oakland was developing at a rapid pace, in large part due to the energetic leadership of University of Pittsburgh Chancellor Edward Litchfield.

Litchfield retained the New York firm Harrison & Abramovitz (known for the Empire State Plaza in Albany, N.Y., and the U.S. Steel Building and the old Alcoa building, Downtown) to consult on campus growth. Among the many projects overseen by Max Abramovitz was the exceedingly ambitious mega-structure to fill Panther Hollow: the “first 21st century city.”

Designing for the Oakland Corp., a jointly owned, Pitt-dominated consortium of seven institutions, Abramovitz proposed a structure to fill the entire ravine straddling Pitt, the Carnegie Museums and Carnegie Mellon University. Envisioned as a research city linking Oakland’s academic and cultural institutions, the mile-long complex would have filled the hollow to the brim, expanding Schenley Park with a series of rooftop terraces and gardens and culminating in a hanging garden at Panther Hollow Lake.

The city would have provided its own services and amenities and supported a series of residential developments. Portions were to be replaced periodically so the overall city remained up to date.

When presented with great fanfare by the Oakland Corp. in 1963, the project was initially estimated to cost more than $250 million, or about $2 billion today. Although the Oakland Corp. continued to promote the project for a few years, it was quietly shelved by 1965, the year Litchfield resigned amid a financial crisis engendered by the university’s rapid growth.

While these projects failed to materialize, they were nonetheless important. First, the national attention they garnered helped position Pittsburgh as an important urban player in the post-war era. Second, they provided the architects with opportunities to think about large-scale solutions for modern cities. Third — and perhaps most important — the discussion surrounding these projects helped galvanize support for, and refine, other projects that did come to fruition.

Chris Grimley, Michael Kubo, Ann Lui and Rami el Samahy are with over,under, a Boston architecture and design firm. Mr. el Samahy also is an associate teaching professor at Carnegie Mellon University School of Architecture. The four curated “HACLab Pittsburgh: Imagining the Modern,” an exhibit of architecture and urban planning in post-war Pittsburgh that runs through May 2 at the Carnegie Museum of Art. The projects mentioned in this story are part of the exhibit.

Correction (posted Nov. 12): The cutline for the illustration displaying a 1952 cover of Charette magazine has been updated. The cover shows the Alcoa building Downtown, not one of the Gateway towers.

First Published: November 8, 2015, 5:00 a.m.