The world we live in today is a world dominated by degenerative capitalism and its monotonic metric of “profit maximization.”

What else should we call an economic system that continuously degrades our oceans, soils, lakes, rivers, forests and atmosphere, while leaving billions of our fellow human beings unhealthy and impoverished?

Degenerative capitalism functions as it does because of an insidious twist in the rules economists use to calculate costs and benefits from our actions in the natural world. In a sleight-of-hand that would make a three-card Monte dealer proud, economists define these environmental costs as “externalities,” and remove them from the books. Refusing to put these costs on the books allows economists defending this system based on extraction and exploitation to claim that we are living in the best of all possible worlds.

“Capitalism” is, of course, not a monolithic, universal, never-changing system. There are no stone tablets with a 3,000-year-old set of immutable rules. To the contrary, one of capitalism’s greatest strengths has been its malleability, as governments and corporations have continually altered the rules of capitalism in response to challenges that appeared to threaten the survival of the system.

Some of the most important of those challenges have come from social movements struggling to ameliorate the worst impacts of capitalism on workers. Those struggles have not been easy. Even simple changes like the abolition of child labor or the adoption of the eight-hour workday required the power of massive social mobilization and the willingness of people to die.

If we want our grandchildren to have a livable planet, it’s time to stop fetishizing “economics” as a God-given set of rules and get on with the political process of eliminating rules that aren’t working and enacting rules that better serve the coming generations.

We are quite aware that our increasingly sclerotic electoral and legislative processes have engendered deep feelings of cynicism, feelings that in turn depress all efforts for political change.

However, even a quick look at history shows example after example of huge changes that took place even as prognosticators of the status quo had insisted for decades that nothing could change.

U.S. intelligence agencies and academics alike failed to predict the collapse of the Soviet Union. Apartheid in South Africa would never end. Ten years ago, who would have predicted that same-sex marriage would be so widely accepted today?

Our challenge is to invent and adopt an economics of stewardship that embraces the concept of continuous environmental improvement. Call it regenerative capitalism.

It’s really not that difficult to think of some straightforward laws that would push us in this direction. All we have to do is leverage the creative energies at the core of the market-economy model to kick off a virtuous cycle of improvement.

To take a simple example, we know that one of the reasons the investment banks almost took down the global economy was because the Glass-Steagall Act that limited their activities was repealed in 1999. Restoring it would not, by itself, restore the system that existed in 1999, but it would create the kind of inhibition on unprincipled risk-taking we want our financial system to have.

To take another long-discussed example, Nobel-Prize-winning economist James Tobin started calling decades ago for a tiny tax on all financial transactions, which would both restrain traders and generate more than enough money to provide every human being with decent food, housing, health care and education.

Or we could adopt the more recent proposal to put a tax on carbon to correct the marketplace’s abject failure to account for the little “externality” of climate change in the price of fossil fuels.

We can hear the groans coming from those who say that even such simple changes cannot possibly happen with a Republican Congress, with the billionaire Koch brothers funding so many political campaigns, and on and on.

But history holds hope even in the face of the darkest despair. No Congress is forever.

What we hope for most of all is that we the people will be able to force the changes we advocate to come about as soon as possible, so that we can start regenerating our world from the strongest possible base.

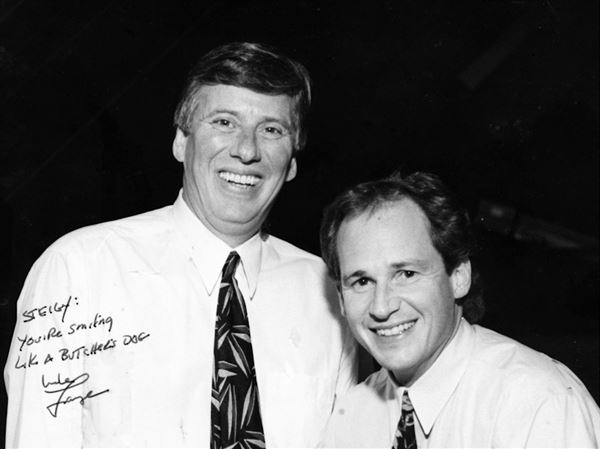

Jock Gill, an Internet communications consultant, served in President Bill Clinton’s Office of Media Affairs. Richard C. Bell has worked in journalism, national electoral politics and environmental research and activism. He is a co-author of the book “Nukespeak: Nuclear Language, Myths and Mindset” and a recipient of the George Orwell Award.

First Published: May 31, 2015, 4:00 a.m.