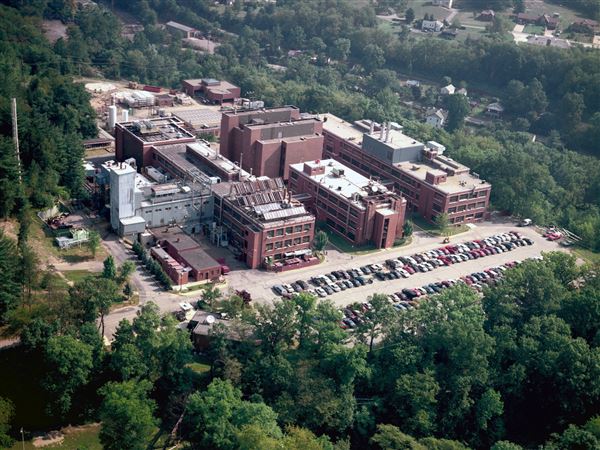

So what goes on over the winter on major highway construction projects when the weather has been bitter cold for weeks and the ground is frozen? A lot, actually.

The Pennsylvania Turnpike’s 13-mile, $800 million Southern Beltway project to connect Route 22 with Interstate 79 has been staged to allow work to continue most days through the winter on projects such as installation of drainage and water lines, placing steel bridge components, clearing brush and staging equipment for the next major excavation project. Crews even are using heaters and building small tents to allow them to pour concrete for the toll road extension despite winter’s wrath.

“Basically, we pay [contractors] for completed projects,” said John Dzurko, engineering project manager for the turnpike. “Many of these projects have milestone dates where they have to have a certain amount of work done by a certain time. How they get to that is up to them.”

For example, if weather interrupts the work schedule one week, a contractor may assign crews to work weekends or work two crews a day to catch up.

Despite many days of bitter cold weather since early December, a crew installing a water line near Beech Hollow Road hasn’t missed a day’s work. Those doing concrete and drainage installation work were shut down for a week earlier this month when temperatures sunk below zero overnight and barely reached double digits during the day.

“[Two weeks ago], concrete wasn’t able to be supplied because it was too cold for the contractor,” so they didn’t work, Bob Kohlmyer, construction supervisor for CDR McGuire, the turnpike's construction manager for this project, said during a tour of construction sites along the Washington-Allegheny County border Wednesday.

“We’re getting it now, so we’re back to work.”

Another factor that encourages work: “When [the contractors] decide not to work, [the crews] don’t get paid.”

Cold is better

In reality, this winter with subfreezing temperatures is better for road construction crews than last year’s relatively mild, wet weather. That’s because heavy machinery can break through frozen ground, rock really doesn’t freeze and mud is the devil in disguise.

“A lot of the crews would rather have it 15 to 25 degrees rather than 35 to 45 degrees,” Mr. Kohlmyer said, because cold is easier to deal with than rain and mud.

“It’s easier to sometimes work with frozen ground,” said Dale Rosinski, project manager for CDR. “Rain just slows everything down. It’s tough.”

Mud, in particular, interferes with working efficiently. It’s hard for workers to move their own legs let alone maneuver equipment.

“Just walking around in mud is miserable,” Mr. Dzurko said. “It puts an extra one or two pounds on each foot. But when the ground freezes, everything is hard. It helps with mobility.”

Jason Hartly, foreman for the crew from Independence Excavating in Cleveland that was installing drainage near the west end of the Findlay Connector, said he’s worked construction for about 13 years and learned to deal with the cold. There are days when he’s crawled out of a trench with frozen pantlegs.

“If you keep moving, you’re OK,” he said. “When it’s 10, 12 degrees, you just layer up. If you get too hot, you just start taking it off.

“I’d rather have that than 95 degrees any day.”

Managing concrete

To the layperson, pouring concrete seems like a warm-weather project. To the road construction industry, winter weather is a challenge, but not an insurmountable one in the right circumstances.

For concrete to cure, it needs a constant temperature between 50 and 110 degrees for a week. In the winter, that means taking special steps to make sure that happens, including using hot water, heaters, tents, warming systems, insulating blankets and thermometers.

Last week, crews poured concrete made with warm water as part of the piers that will support a bridge over Little Raccoon Run. A portable system heated the concrete once it was poured and the site was wrapped with insulation and plastic to hold the heat in.

But crews can’t just pour the concrete and forget it. Someone monitors the thermometer to make sure the temperature stays in the right range and removes some aspects of the warming system over time because a chemical process in the concrete creates its own heat source.

“You try to keep it in the range because if you have to start [the seven-day curing process] all over again, it’s tough to catch up on a project,” Mr. Kohlmyer said.

The turnpike officials and private construction managers keep track of progress through monthly meetings with contractors and subcontractors on the project. The key is for the contractors to meet completion schedules so the next part of the project can begin at the scheduled time.

On this project, the turnpike has done its best to schedule excavation and drainage work in the winter and bridge construction and pouring concrete in warmer months.

“If they are behind schedule, we ask how they are going to catch up,” Mr. Dzurko said. “That gives us a hammer to say you need to speed this up. You don’t want to get to where you have six months of work left and one month to finish it.”

Installing drainage

Overall, Independence Excavating will install 43,000 linear feet of drainage pipe and 436 concrete inlets, manholes and other structures in the 4-mile segment of highway it is building between Quicksilver Road and Route 22. The pipes range in size from 18 to 96 inches in diameter and usually drain into a series of massive stormwater ponds built last year.

Crews on Wednesday were working at three different sites in Robinson Township, Washington County: One end of the new Beech Hollow connector road and the spot where the new road will connect with the west end of the Findlay Connector still were slightly frozen, but the other end of Beech Hollow where a diamond interchange will connect to the new highway was, in Mr. Kohlmyer’s words, “a sloppy mess” with 6-inch deep thin mud.

Regardless, the crews trudged on, six to 12 workers at each site, some using excavators to dig trenches through dirt or rock and others working inside of trench boxes to install the pipe. The steel and concrete boxes are placed in the trenches to prevent them from collapsing and crushing workers.

And despite temperatures below freezing, the crews did precise, delicate work.

At the Findlay Connector site, crews used a tricky method to install the final connecting piece of a 36-inch-diameter drain.

After operator Keith Randolph used the bucket of his excavator to lower the 12-foot piece of pipe into the trench, Mr. Hartly joined two other workers in the trench box to help guide the piece of corrugated high-density polyurethene into place. But because it was the last piiece, it overlapped on each end.

To make it fit, Mr. Hartly, whose only visible body part was his gloved left hand, used hand signals to direct Mr. Randolph to use the bucket to push the pipe and compress it so it would fit in place. At times, the bucket was a foot or less from Mr. Hartly’s head.

“I won’t work in that hole with everybody [operating the excavator],” Mr. Hartly said. “I’ve worked with him for years. You have to make sure that guy doesn’t want to hit you.”

localnews@post-gazette.com or 412-263-1601

First Published: January 30, 2018, 4:02 p.m.

Updated: January 30, 2018, 4:02 p.m.