The U.S. Supreme Court ducked the chance to rule on the issue of partisan gerrymandering Monday, returning two meaty cases to lower courts on narrow procedural grounds. By not taking up the broader question of when partisan gerrymandering violates the constitution, the justices left the status quo in place.

“This was the ultimate in punting,” said Joshua A. Douglas, a law professor at the University of Kentucky and expert on election law.

However, the court’s ruling in the Wisconsin case, Gill v. Whitford, provided some clarity on what types of cases people can bring, saying that individuals may largely challenge partisan gerrymandering in specific districts rather than based on the statewide map. Because partisan gerrymandering is meant to skew a statewide map to give one party an advantage overall, this will limit cases that can be brought in federal court. The state case that overturned Pennsylvania’s congressional map this year, for example, challenged the entire state map and not an individual district.

The second case, Benisek v. Lamone out of Maryland, did challenge an individual district — but the Supreme Court returned that case to a lower court as well Monday on procedural grounds.

Lawyers, advocates, politicians, and others have been anxiously awaiting the Supreme Court opinion for months.

What were the two cases?

Both cases alleged extreme partisan gerrymandering at the hands of lawmakers, saying voters were discriminated against because of their partisan affiliation in an attempt to dilute their vote. Gill v. Whitford accused the Wisconsin state Legislature of drawing state district lines to favor Republicans. Benisek v. Lamone accused Maryland’s Legislature of drawing a U.S. House of Representatives district to favor Democrats, flipping the seat from a safe Republican seat to a safe Democratic one.

The Maryland case argued that drawing lines to favor Democrats effectively punishes Republicans for their political speech and affiliations, falling afoul of the First Amendment. The Wisconsin case also used the First Amendment, along with a Fourteenth Amendment claim that the partisan gerrymandering violated the voters’ constitutional right to equal protection under law.

Both cases essentially laid out a three-part test for gerrymandering: partisan intent, partisan effect, and lack of neutral reason for the map. Basically, the plaintiffs tried to prove that lawmakers meant to draw a skewed map; that the map did in fact skew votes and election results; and that no other reason, such as the “political geography” of how voters are distributed, could explain the map’s skew.

Gill v. Whitford was argued in October, and Benisek v. Lamone was argued in March.

What did the U.S. Supreme Court rule today?

“The court decided it didn’t want to decide,” Mr. Douglas said. “That’s essentially what happened.”

In Gill v. Whitford, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that the plaintiffs did not have standing because their suit challenged the entire state map and did not show it had injured them.

“To the extent the plaintiffs’ alleged harm is the dilution of their votes, that injury is district specific,” Chief Justice John Roberts wrote in his opinion. The other justices joined his opinion or concurred in part; none dissented. “An individual voter in Wisconsin is placed in a single district. He votes for a single representative. The boundaries of the district, and the composition of its voters, determine whether and to what extent a particular voter is packed or cracked.”

In Benisek v. Lamone, a district court had denied the plaintiffs’ request for a preliminary injunction, staying the case while the Supreme Court ruled in Gill v. Whitford. The plaintiffs appealed that decision to the Supreme Court.

On Monday, the court said that the district court had appropriately denied the preliminary injunction request.

Both the Wisconsin and Maryland cases can now continue at the lower courts, but the Supreme Court took no actions Monday that would set guidelines for redistricting.

“We have no standards, we have no answers. Partisan gerrymandering claims live on potentially in theory, but we don’t know how the court will view them or how to proceed,” Mr. Douglas said. “We’re basically at the same place we were before the cases.”

The difference, he said: “We know partisan gerrymandering claims have to be brought district by district.”

Does this change anything in Pennsylvania?

Not immediately. The state’s congressional map is set for the 2018 elections, and there is almost no chance it could change. The maps for the state House and Senate districts have not changed.

OK, how does this affect Pennsylvania in the future? Does it affect other states?

Nothing massive changes right now, given that the court did not rule on the actual issues of partisan gerrymandering. But by ruling in Gill v. Whitford that individuals generally can’t challenge an entire state map, the court has limited the types of cases that can be brought.

“It’s a fairly big deal at this point,” said Michael McDonald, a political science professor at the University of Florida who is an expert witness in the Maryland case. “Up until now, partisan gerrymandering claims have been made by individuals making these claims against the districts as a whole. So if you’re going to have individuals make claims, the Supreme Court is saying basically, they can only make claims against the district they reside in. They can’t make a claim against the entire plan.”

In recent years, political scientists, lawyers, and mathematicians have sought to create mathematical tests that would allow a political map to be measured for partisan skew. These measures, including the “efficiency gap” used in the Wisconsin case, work at the statewide level by analyzing vote counts. After all, many political scientists and lawyers point out, the point of partisan gerrymandering is to give a party an advantage in the number of seats — if a map is skewed far enough, a party can win more seats in Congress or a state legislature than they would under a neutral map.

Those tests for gerrymandering are now less useful in federal cases, though they remain useful tools for lawmakers and at the state level, McDonald said.

Who can challenge an entire statewide map?

Mr. McDonald also noted that there is a line in Justice Roberts’ opinion that suggests political parties may be able to bring statewide claims.

Marc Elias, a high-profile Democratic lawyer, took notice of that line almost immediately.

If political parties or other statewide groups can challenge a political map as a whole, that would mean the efficiency gap and other measures can still be used — just with different plaintiffs bringing the challenges.

“It’s a point of clarity,” said Michael Li, a redistricting expert at the Brennan Center for Justice at New York University. “Those claims can continue going forward; they will just be brought by different people. They won’t be brought by individuals, they’ll be brought by organizations.”

Justice Elena Kagan’s concurrence in Gill v. Whitford also demonstrates how statewide tests can be useful for district-level challenges, Mr. Li said, if statewide intent to gerrymander can be proven to be carried out at the district level.

“You prove that there’s a statewide intent and then you say, ‘OK, was this statewide intent executed at the individual district level, look at Goofy-kicking-Donald-Duck?,’ and the answer is yes,” he said.

Wait, didn’t Pennsylvania already fix this?

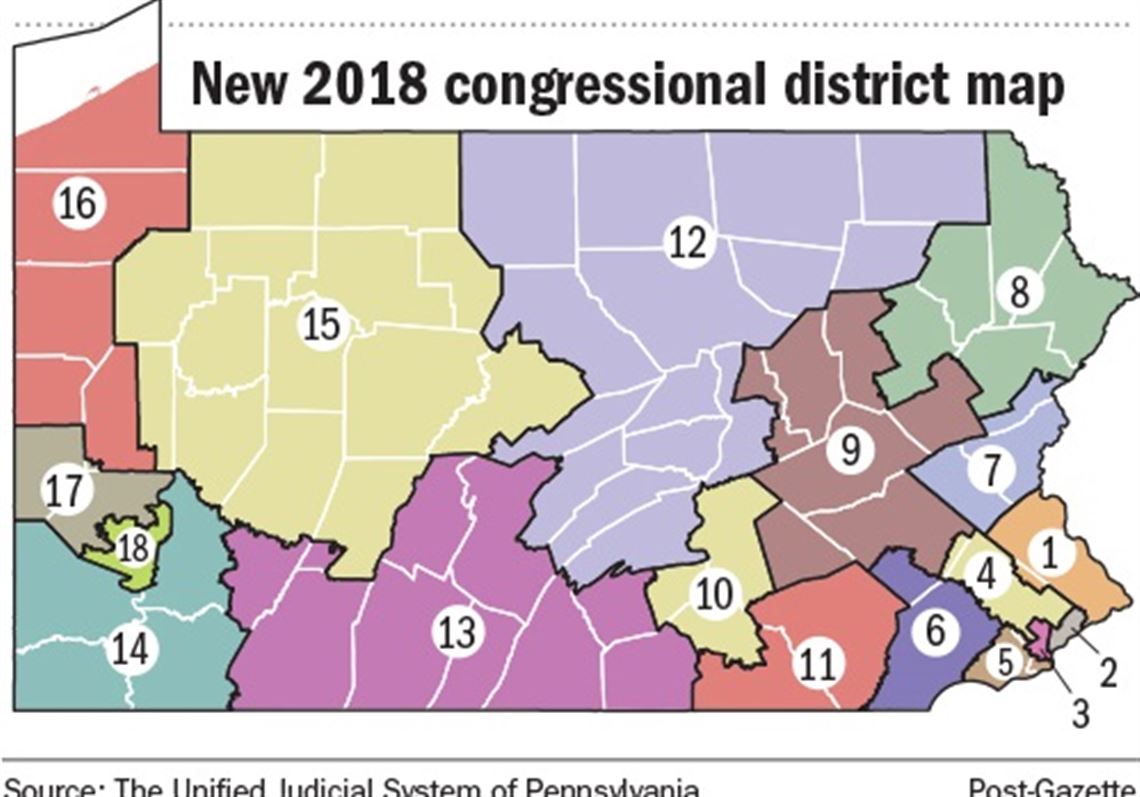

Not exactly. The congressional map Pennsylvania adopted in 2011 was considered one of the worst in the nation’s history as an extreme partisan gerrymander. Under the map, which was drawn by a Republican-controlled General Assembly and signed by Republican former Gov. Tom Corbett, three election cycles ended the same way: Republicans won the same 13 out of the state’s 18 seats in a battleground state where statewide votes are split evenly between the two major parties.

The League of Women Voters of Pennsylvania sued last year in state court, saying the map unfairly discriminated against Democrats. In January, the Pennsylvania Supreme Court overturned the map and then imposed its own. That’s the map being used for the 2018 congressional elections. A nasty legal and political fight ensued, but ultimately the map was set.

So Pennsylvania no longer has the map that was infamously skewed toward Republicans. But no one is exactly happy with the way the new map was delivered: drawn by a well-known Stanford University professor for a state Supreme Court made up mostly of elected Democrats. Even reform advocates agree that this process was not transparent and is not the change they have been fighting for.

First Published: June 18, 2018, 6:17 p.m.