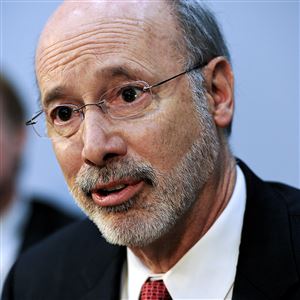

The Pennsylvania Supreme Court on Tuesday agreed to take a case filed by the Philadelphia district attorney’s office challenging Gov. Tom Wolf’s moratorium implemented last month on capital punishment in the state.

District Attorney R. Seth Williams asked the court to take up the matter involving a defendant named Terrance Williams, who was scheduled for lethal injection today.

Although Seth Williams asked that the court take the case on an expedited basis, the court refused, and it will be heard on a standard calendar, which means that both sides will file briefs and replies over the next several months, and oral argument will be scheduled at a date in the future.

It will probably be more than a year before any decision is reached, and University of Pittsburgh law professor John Burkoff said it could be even longer if the court decides it wants two new justices, who will be elected later this year, to consider the case as well.

Mr. Wolf announced on Feb. 13 that he was instituting a moratorium on the death penalty in Pennsylvania, saying that it was not an “expression of sympathy for the guilty on death row, all of whom have been convicted of committing heinous crimes.” Instead, he continued, it was “based on a flawed system that has been proven to be an endless cycle of court proceedings as well as ineffective, unjust and expensive.”

He cited nationwide statistics that show 150 people have been exonerated from death row, including six in Pennsylvania.

A bipartisan commission was asked in 2011 to review the effectiveness of capital punishment in Pennsylvania, and Mr. Wolf said the moratorium will be in place until recommendations and concerns from that are addressed.

Because of the governor’s actions, Terrance Williams, who was sentenced to death for killing a man with a tire iron on June 11, 1984, received a temporary reprieve from his execution warrant, signed by former Gov. Tom Corbett.

But in his filing, Seth Williams argues that Mr. Wolf’s action was lawless and unconstitutional.

“Merely characterizing conduct by the governor as a reprieve does not make it so,” the prosecutor’s filing said.

Instead, it continued, “At all times in Pennsylvania history a reprieve has meant one thing and only one thing: a temporary stay of a criminal judgment for a defined period of time, for the purpose of allowing the defendant to pursue an available legal remedy. The current act of the governor is not a reprieve. Nor, indeed, could it be. There is no remaining legal remedy available to defendant. He received exhaustive state and federal review. He sought pardon or commutation and it was denied. There is nothing legitimate left to pursue and no remedy to wait for.”

To halt the imposition of the death penalty on a defendant, the district attorney’s office continued, the sentence must be commuted, which can be done only with unanimous agreement by the state Board of Pardons.

Seth Williams accused the governor of usurping judicial function.

But in the governor’s response, his attorneys said what he was doing is temporary — a reprieve — and requires no input from the Board of Pardons.

“The governor has ‘exclusive authority’ and ‘unfettered discretion to grant a reprieve after imposition of sentence and on a case by case basis,’ ” they wrote, quoting an earlier court case.

The response also notes that there is no time limitation included in the Constitution for how long a reprieve might last, meaning the governor may issue it as he sees fit.

Cameron Kline, a spokesman for the Philadelphia district attorney’s office, said he was pleased the Supreme Court took the case. Even though no one has been executed in Pennsylvania since 1999, Mr. Kline said, it is an important question.

“The district attorney has said his job is to enforce the laws on the books in Pennsylvania,” he said. “Regardless of how infrequently the death penalty is used, it is still the law, and that is why he challenged the governor.”

Mr. Burkoff said that the full importance of the case — and how the court ultimately rules — is probably more for the long term than the short.

“In the long run, it makes a big difference. Governors change. Attitudes change.”

First Published: March 4, 2015, 5:00 a.m.