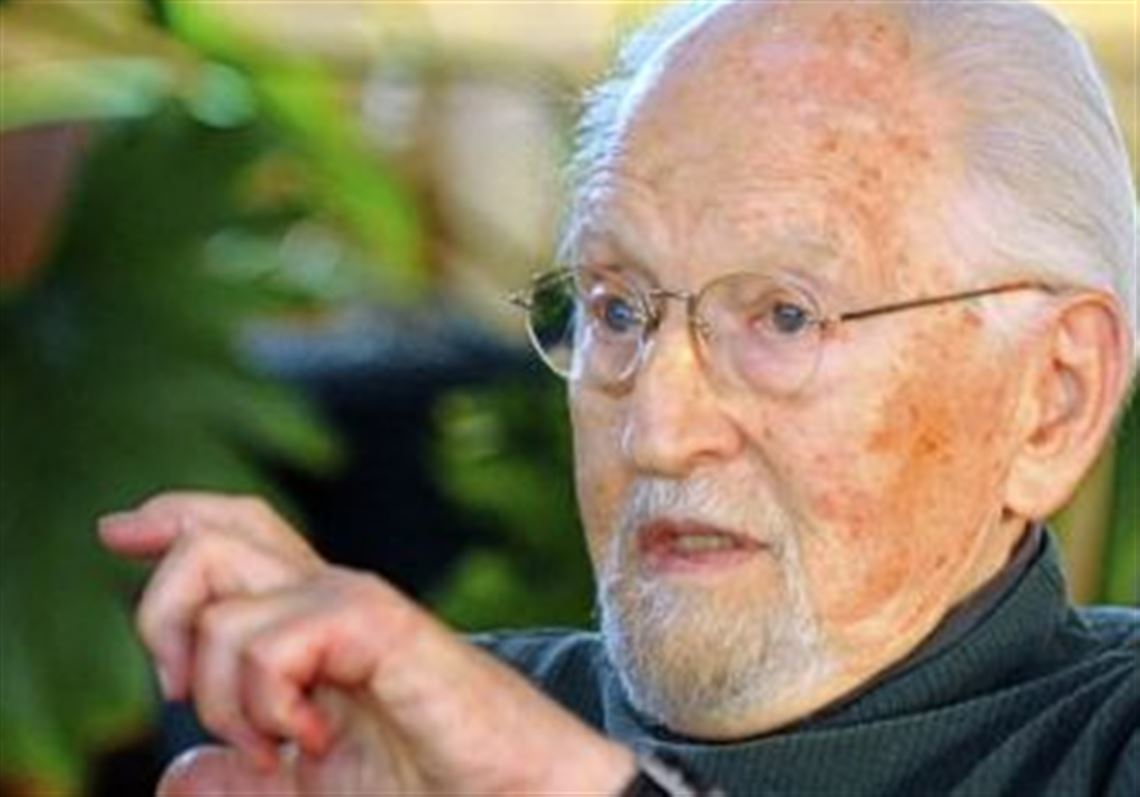

As the last surviving member of the team that developed the Salk polio vaccine in the 1950s, Julius Youngner was justifiably proud of his contribution to that landmark effort.

“Dr. Youngner made monumental contributions to the field of virology,” Vincent Racaniello, Higgins Professor of Microbiology and Immunology at Columbia University, said in a statement. “For most, simply working with Jonas Salk on the development of the polio vaccine would be enough for a career; he also made important contributions to our understanding of the antiviral roles of interferon, cell culture and other vaccines.”

But Mr. Youngner, who died Thursday at the age of 96, never forgave Jonas Salk for his failure to acknowledge Mr. Youngner and the other members of the research team that created the vaccine against the crippling disease.

In a revealing oral history done by the local chapter of the National Council of Jewish Women in 1992-93, Mr. Youngner described what happened. Dr. Salk’s announcement of the success of the polio vaccine in field trials in 1955 created a sensation, he said, and the group that had funded the effort, then known as the National Foundation for Infantile Paralysis, knew that “it was much easier to continue raising money when you have a hero, and they had an enormous public relations department that took up Jonas’ name as the hero, which he deserved.

“But in the meantime, Jonas was, how shall I say, not very generous to his colleagues and he made sure that nobody else was ever mentioned.”

To add insult to injury, Dr. Salk’s wife later called Mrs. Youngner and said, “You know, we’re really disappointed in your husband, because he hasn’t called Jonas and congratulated him.” Mrs. Youngner responded with a brusque reply, and the two couples, who had once been close, never socialized again.

Years later, Dr. Salk’s son, Peter, made efforts to recognize Mr. Youngner’s contribution — as well as the contribution of many others — to the creation of the polio vaccine.

“The really important thing to recognize is that the development of the polio vaccine at the University of Pittsburgh was a team effort. Everyone who took part in that had a role to play, and Dr. Youngner had a significant and primary role in what was undertaken,” the younger Dr. Salk said Saturday. “I think my father recognized the importance of the team, and if there were circumstances in which that wasn’t adequately expressed, I would feel that it needs to be expressed now and very clearly so.”

Speaking at Pitt’s School of Public Health in January, Peter Salk again gave credit to Mr. Youngner. “If I’m remembering correctly what I said,” Peter Salk recalled, “I think it’s absolutely fair to say that had it not been for Dr. Youngner the vaccine would not have come into existence.”

While Mr. Youngner’s name was always associated with the polio vaccine breakthrough, he went on to have a distinguished career as a research scientist at the University of Pittsburgh. He helped discover a key immune system component known as gamma interferon, and later, his team developed a vaccine for equine influenza, saving the lives of horses around the world.

“Dr. Youngner is best known as a pioneer and member of the Polio Vaccine team in the 1950s. However, as with anything, lifetime achievement supersedes even monumental success like those realized by the Salk Team. In the 60 years since the polio vaccine launched, Dr. Youngner became one of the seminal figures in contemporary virology, making a positive impact on millions of patients each year, and on science for decades,” Christopher Molineaux, president and CEO of Life Sciences Pennsylvania, said in an email.

“He loved science — the scientific method and research — he loved it. That was one of the energies that guided him,” Mr. Youngner’s son, Stuart, said Friday. “And I think he was also dedicated to … helping people.”

According to a statement released by Pitt, Mr. Youngner published about 200 papers and mentored dozens of students, “many of whom went on to make great contributions to the field themselves.”

“Something he was very proud of was he was a great teacher and mentor,” Stuart Youngner said. “He gave to his students and he spent a lot of time with his junior faculty and Ph.D. students, many of whom went on to very, very successful careers.”

He continued to operate a lab at Pitt into his 80s, and even in his 90s, and he occasionally came into his office to work, lab staffers said.

“Juli’s infectious curiosity has fueled his own research and influenced all who had the privilege to work with him,” Arthur S. Levine, Pitt’s senior vice chancellor for the health sciences and John and Gertrude Petersen Dean of the university’s School of Medicine. “As a direct result of his efforts, there are countless numbers of people living longer and healthier lives.”

When he was asked in the Council of Jewish Women interviews why he had gone into infectious disease research, he said it was partly because he had been ill so much as a child, nearly dying of pneumonia at the age of 7.

When he contracted lobar pneumonia in the late 1920s, Mr. Youngner recalled, there were no antibiotics. Instead, patients would go through a critical period called “the crisis,” after which they died or recovered.

“I remember calling my mother to my bedside and saying, ‘I’m going to die now,’ but in a couple of hours I was well.”

Still, the pneumonia had given him a secondary infection that ate through his chest wall and infected a rib. Doctors decided he needed surgery, but they were afraid to give him anesthesia because of his weakened lungs.

“So they strapped my legs to table, and two nuns held my arms and another held my head and they prayed while they operated on me. To this day I can remember the feeling of the saw on that rib. Later in life when I had to have some minor surgery, I put it off for years because I was so affected by this episode.”

Mr. Youngner was born in New York City. A brilliant student, he graduated from high school when he was 15, and then went on to get his bachelor’s degree at New York University and a master’s and doctorate in microbiology at the University of Michigan. He met his first wife, Tula Liakakis, in Michigan, and they married in 1943.

During World War II, after he was drafted into the Army, Mr. Youngner worked for the Manhattan Project, testing the effects of uranium salts and plutonium on lab animals at the University of Rochester. During those years, he and his colleagues speculated that they were working on some kind of nuclear propellant for missiles.

“We never dreamed it was a bomb; that didn’t occur to me until the day the [atomic] bomb was dropped.”

After a brief stint at the National Cancer Institute, Mr. Youngner came to Pittsburgh in 1949 to continue his work on learning to grow viruses in live cell cultures, and that is where he met Dr. Salk, who told him he would fund Mr. Youngner’s research, as long as one of the germs he grew was the poliovirus.

Mr. Youngner made three key advances in the vaccine research. He first figured out a way to break down monkey cells so that the team could grow large amounts of poliovirus in the lab. Then, after the Salk group began to work on a vaccine, Mr. Youngner developed a way to inactivate the virus so it could safely be injected as a vaccine, and then developed tests to see how effective it was in the first human patients. He never intended to remain here, but “I got so involved in [the polio vaccine effort] that I decided to stay in Pittsburgh.”

“Julius Youngner once told a reporter that he intended to stay at the University of Pittsburgh for only a short time following his work on the Manhattan Project. But he soon fell in love with Pitt and the research opportunities here. I am grateful he stayed and that his work, with Jonas Salk and others, led to the polio vaccine. He was one of the world’s preeminent virologists and our University community will miss him immensely,” Patrick Gallagher, chancellor of the University of Pittsburgh, said in a statement.

As the vaccine project moved forward, Mr. Youngner said, “I was Mr. Inside and Jonas was Mr. Outside. He went out and got the money and built the lab.” The success of the Salk vaccine was quickly evident. The number of polio cases went from an average of 35,000 a year before the vaccine to fewer than 2,500 two years later.

By now, polio has been virtually eradicated in the United States, except for occasional outbreaks among groups that don’t get the vaccine. Today, only three countries in the world, Nigeria, Pakistan and Afghanistan, have not stopped transmission of polio, according to the World Health Organization. Asked years later to describe his impressions of Dr. Salk, Mr. Youngner said he was “smooth, glib, dynamic and self-absorbed, and a man who believed his own press notices.”

In the end, he concluded, “there was some merit for me in not having the kind of adulation Salk did because I was able to keep working and being productive and actually, he never did another thing scientifically in his career.”

Dr. Salk, with funding from the paralysis foundation, which had become known as the March of Dimes, went on to head his own research institute in La Jolla, Calif., while Mr. Youngner stayed on in Pittsburgh for the rest of his career. His first wife died in 1963 after suffering from Hodgkin’s disease for nearly 20 years. A year later, he married his current wife, Rina Balter, who went on to become an expert in the use of industrial imagery in art. He has two children from his first marriage, Stuart, a psychiatry and bioethics professor at Case Western Reserve University in Ohio, and Lisa, a ceramic and computer graphics artist in Albuquerque, N.M.

Reflecting on his long career in Pittsburgh, Mr. Youngner said: “I’m not one to have regrets, because my desires have been fulfilled. The things I had no control over, like disease that killed my wife — I regret that was out of my control. What was in my control, I always managed to make the right decisions in my career. I was not one of these people who planned ahead. Opportunities, when I was ready for them, appeared for me.”

Donations in Mr. Youngner's name can be made to the Pittsburgh Hebrew Free Loan Association. No service is planned.

Former Post-Gazette science editor Byron Spice and staff writer Andrew Goldstein contributed to this article. Mark Roth, a former Post-Gazette enterprise reporter, retired in 2015.

First Published: April 28, 2017, 10:33 p.m.