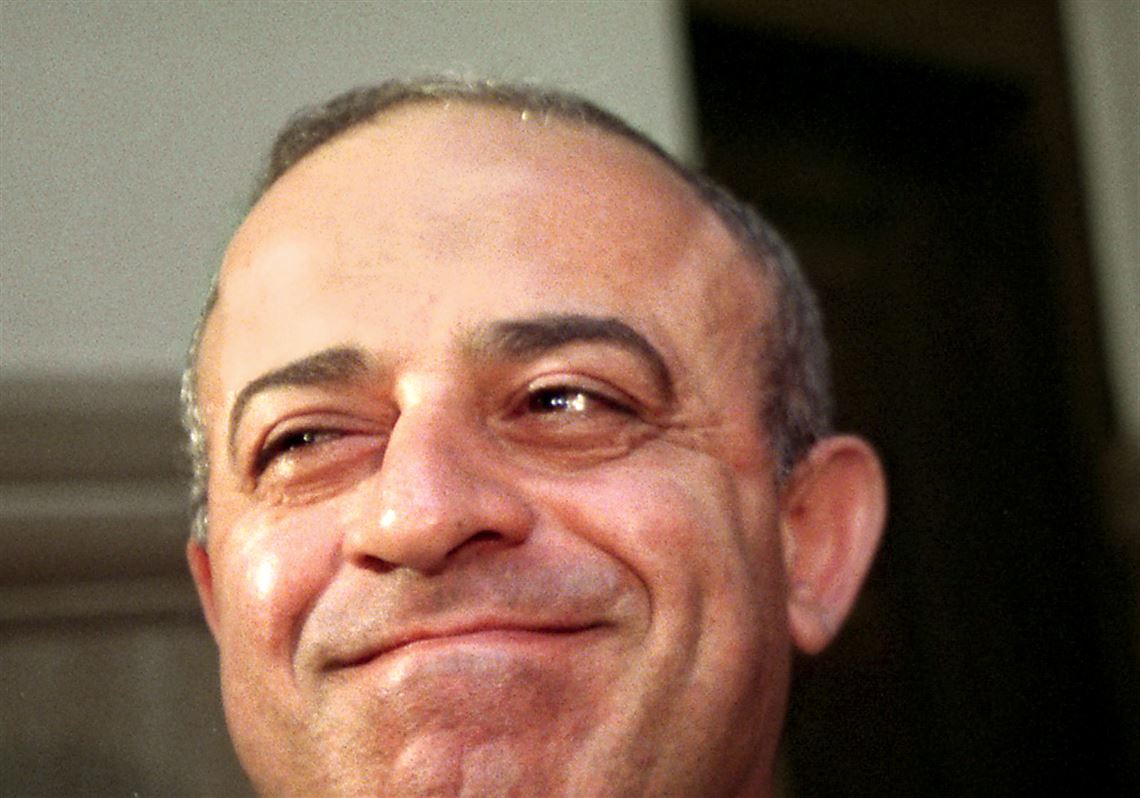

Sherif Abdelhak, the former CEO of what was once the largest health system in Pennsylvania who was blamed for its spectacular collapse in 1998, died quietly seven months ago in Florida.

Despite nearly two decades having passed since the demise of the Pittsburgh-based Allegheny Health, Education and Research Foundation — commonly known as AHERF — one of Mr. Abdelhak’s sons, John, said his father still carried a burden from what happened in Pittsburgh.

“He was a loving father, but he never really recovered after that ordeal with the hospital,” John Abdelhak said Friday.

He said his Egyptian-born father, who was 68, died Aug. 2, 2014, after an 18-month battle with cancer.

Mr. Abdelhak’s death had escaped public notice until now and was intentionally quiet. Neither his sons from his two divorces, nor his more recent third wife, took out obituaries for him.

In addition, he appears to have changed his last name to Abel, which is how it was listed on his Certification of Death — something his son was not aware of. His third wife, Anna, goes by the last name Abel.

His son said he returned a call to a reporter to talk about his dad despite knowing that his father “probably wouldn’t want you to write anything about him.”

The bankruptcy of AHERF — which at its peak had 30,000 employees, two medical schools and 14 hospitals stretched across two states — was at the time the largest nonprofit insolvency in U.S. history, and continues to impact health care in the state.

That impact included the presence of the state’s first for-profit hospitals after Tenet bought AHERF’s Philadelphia hospitals out of bankruptcy and the creation of the West Penn Allegheny Health System, the precursor to today’s Allegheny Health Network, after AHERF-owned Allegheny General Hospital merged with West Penn Hospital. Perhaps most resoundingly, AHERF’s death paved the way for the rise and ultimate hospital market dominance of UPMC in the Pittsburgh area.

And, in a Post-Gazette story in 2007, Mr. Abdelhak made it clear AHERF’s collapse still was impacting him as well.

"I don't have a life," he said then. "They managed to destroy it 10 years ago."

The spectacular flameout of AHERF, and the blame that ultimately fell on Mr. Abdelhak, left former colleagues uncomfortable commenting on his death.

Four former AHERF employees who were reached Friday said they did not want to comment publicly about Mr. Abdelhak. None had stayed in touch with him.

“The last time I talked to him was the day they fired him,” said one former colleague who worked closely with him at AHERF but asked to remain anonymous.

It was still difficult to talk about Mr. Abdelhak, the colleague said, because: “It was so bloody ugly in the end. It just turned everyone’s life upside down.”

“It’s a shame, too,” the colleague added, “because there is no doubt that he had a great idea to create an academic medical center health system across the state. He just went a bridge too far in Philadelphia.”

Philadelphia was where AHERF had bought two medical schools and eight hospitals and stretched itself too thin — something Mr. Abdelhak would not acknowledge until it was too late.

The expansion was too fast and the system began to bleed red, with losses of nearly $1 million a day. Creditors were owed nearly $1.5 billion.

“He just let his sense of impunity get the best of him, and maybe his ego,” the colleague said. “But he was a dichotomy: He could be a hard [head] but he could also be real sensitive.”

After being charged with more than 1,500 counts related to the collapse of AHERF, Mr. Abdelhak pleaded guilty in 2002 to a single misdemeanor of misusing charitable funds. He was sentenced to 11½ month to 23 months in jail, which he was allowed to serve in alternate housing.

Mr. Abdelhak would later complain that he was fired without being paid what he was due by AHERF.

His troubles continued after he served his sentence. He divorced his second wife, Marlynn Singleton, a former KDKA-TV anchor and now a physician. At one time, she was AHERF’s director of public relations. Dr. Singleton did not return a call for comment.

Mr. Abdelhak’s first wife, Mervat Abdelhak, also a physician, said Friday she did not want to comment.

“It just opens up a lot of old … I’d just prefer to not talk about this,” she said.

In the years after he got out of jail, Mr. Abdelhak had other business problems, including a failed oil-buying venture in which he was accused of trying to buy oil illegally from Iraq or Iran, in violation of a presidential order banning such purchases from those countries. He filed for personal bankruptcy in 2004 and was later ordered by U.S. Tax Court to pay $500,000 in back taxes.

His Pittsburgh associates lost touch with him. “He really just fell of the face of the Earth,” attorney Judith Olson, who once represented Mr. Abdelhak, told the Post-Gazette in 2007. Asked if there were anyone in Pittsburgh still close to him, she said, "He didn't have a lot of friends. ... I never learned anything personal about him at all. He was very quiet.”

But Mr. Abdelhak did seem to find some happiness later in life.

After bouncing around and settling for a time in Kentucky — a place he told a reporter in 2007 he chose because “it’s not Pittsburgh” — Mr. Abdelhak lived the last years of his life in Palm Beach, Fla.

He married again. His wife, Anna Abel, a primary care physician in Palm Beach, Fla., did not return a call Friday seeking comment.

He reconnected with his family. Mr. Abdelhak had become distant from relatives after the fall of AHERF. But his son, Sherif Jr., said that “over the last year we started talking more once we found out he was sick.”

The family had a private, quiet service for Mr. Abdelhak, his son said.

“We’re happy with our memory of our father,” he said. “We miss him very much.”

First Published: March 28, 2015, 4:00 a.m.