It’s easy to indulge ourselves over the holidays when we’re eating, drinking and being merry among friends and relatives. But when the Champagne glasses are shelved and the New Year’s Eve confetti is swept away, many minds turn to a fresh start the morning of Jan. 1.

Enter Dry January — a 31-day, alcohol-free challenge that promises clarity, better health and perhaps a bit of redemption after the excesses of December. But beyond hashtags and mocktail recipes, what benefits does this abstinence impart?

Local psychologists and doctors say those who will benefit most from Dry January aren’t the social drinkers among us, but instead the moderate drinkers who may be starting to consider whether their drinking is negatively impacting their health, relationships and overall life.

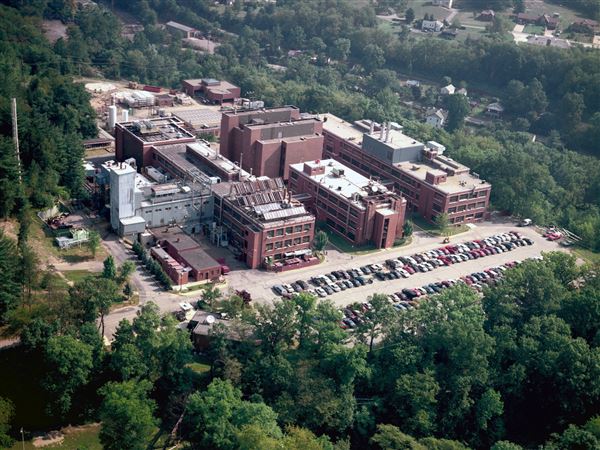

“A lot of people reflect on Dry January as a way to figure out if they want to take a break from alcohol for a month … and not go back to it,” said Antoine Douaihy, professor of psychiatry and medicine in the University of Pittsburgh’s psychiatry department.

“If you stop drinking for a month, casual drinkers or social drinkers don’t think much of it. They’re not going to care.”

But for those who have realized “maybe I’m consuming too much alcohol,” Dry January presents opportunities to reflect and identify the reasons why they drink excessively, what the underlying causes are — whether it’s simply social drinking, using it as a coping method for stress or anxiety, self-medicating for pain, to forget about financial issues or other reasons, Douaihy explained.

Dry January can activate one’s self-regulatory processes to observe, understand and change the way they use alcohol.

“When people step back and take that look … it kind of helps them also to realize that, ‘Maybe I don’t want to drink at all after that. I’m feeling better physically, I have more energy, more drive to do things, a better quality of life, I’m saving some money.’”

What started it all

Dry January officially launched as a 2013 campaign under the organization Alcohol Change UK, although the practice has roots that extend as far back as 1942, when Finland had its own Sober January to help in the war against the Soviet Union, according to Time magazine.

Many who practice Dry January achieve heightened awareness or insights that could help them to make more informed, deliberate drinking decisions in the future, said Kasey Creswell, associate professor of psychology at Carnegie Mellon University.

“People often gain a lot of insight into their alcohol habits by taking a break from alcohol. Setting an intention and stepping back for a defined period — January — can really help people look at their patterns of use from a fresh perspective,” Creswell said.

When people alter their drinking routines, they naturally become more aware of “when they drink, why they feel inclined to drink,” she said. Specific cravings can alert a person to their previous drinking patterns.

“For instance, they could notice that stress or certain social situations or even particular times of the day prompt these cravings. Or they might notice how things like their mood and their sleep quality and their energy levels change on days when they're not drinking alcohol and the day after.”

Health perks of Dry January vary and can include anything from weight loss, lowering blood pressure and better sleep quality to relieving anxiety, depression and overall mental health, Creswell said.

The most influencing factors on potential benefits are how often and how much the person imbibed in the past, and whether their future drinking habits remain the same, diminish or disappear altogether, she said.

Alcohol can kill

Excessive drinking is one of the leading causes of preventable deaths, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Excessive alcohol use causes about 178,000 deaths each year in the U.S. and shortens the lives of those who died by an average of 24 years, resulting in a total of approximately 4 million years of potential life lost, per the CDC. Alcohol-related deaths include chronic conditions caused by long-term drinking, such as cancer, heart and liver disease, and more, and binge-drinking or drinking too much on one occasion, including alcohol poisoning, vehicle crashes and suicides.

An average 6,600-plus Pennsylvanians die of causes related to excessive drinking every year, per the CDC. Binge-drinking in the state is slightly higher than at the national level, at 18% of adults versus 17%, respectively.

The CDC estimates that there are more than 488 deaths each day in the U.S. from excessive alcohol use — about 20 people every hour. A majority of alcohol-related deaths are among those ages 35 and older.

Heavy drinkers — especially those classified as having an alcohol use disorder — should never attempt a complete cessation of alcohol intake on their own, said Mark Guy, a doctor at Allegheny Health Network's Center for Recovery Medicine. He specializes in addiction medicine and substance use disorder.

“The risk needs to be made very, very clear. People, in general, do not have life-threatening changes when stopping opioids. It’s horrible, but generally not life threatening. Same for stimulants. Benzos and alcohol cessation for those who have developed a dependence can result in death. At any given time, we have several patients in our ICUs being managed for this,” Guy said in an email. Benzodiazepines are a class of depressants used to treat anxiety, insomnia and seizures.

This “complicated withdrawal” can have symptoms that range from agitation, anxiety and sweats to nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, confusion, seizures and full-blown encephalopathy, which could include amnesia, agitation, delirium, hallucinations and more.

“So, it is not the duration of the month, but the abruptness of the cessation,” Guy said. “And people cannot ‘feel’ their way through — a generalized tonic-clonic seizure can blow in out of nowhere within six to 12 hours after the last drink.”

“[Dry January] is a really good idea in general — it is good for folks to take a breather from the use of alcohol and reflect on what they want their relationship with alcohol to be going forward, seeking their most healthy self. It can be a bit tricky, and health care folks are glad to support their desires on their journey into 2025,” Guy said.

Calling it quits

It might seem counterintuitive, but the more often a person tries to quit increases the chances that they will quit successfully one day, said Creswell, adding that studies have shown that people who have successfully kicked a nicotine habit try an average of seven times before making the change permanent.

In addition, Dry January adherents should be vocal about their goals. Research has shown that when you voice your intentions to your friends and family, it strengthens your resolve to follow through, Creswell said. “People who do share it often report feeling more committed and their peers often can be supportive or provide encouragement or even join the effort.”

One of the best ways to approach Dry January is as a part of a group, Douaihy advised.

“When a lot of people are doing it together, they can motivate each other, similar to a buddy system. It increases the likelihood of people making this behavioral change” and completing the entire month of abstinence, he said. “When you have 15 people who come together and decide to stop drinking together … that can have such an impact and facilitate behavior change.”

The best self-control or self-regulation strategies are anticipating situations and scenarios that could be troublesome.

“If you're on a diet, it's not having the bag of Oreos out on your counter for you to see. If it’s your intention not to drink, maybe you plan to order that mocktail at the bar,” Creswell said.

Taking a thoughtful break can also help someone “be more assertive and more capable of saying no to alcohol” in the future, Douaihy said. It can help create that inner monologue to deal with people who, in the past, may have been pushed by their friends and family to overindulge.

Some Dry January participants may also find that outright avoiding alcohol-centered gatherings works better for them than mimicking drinking behaviors via mocktails and other non-alcoholic beverages.

“You can decide that [going to bars] is not going to be something that you participate in and you organize something else that doesn't revolve around alcohol,” Creswell said. “If I feel stressed out at work, then I'll unwind by taking a walk or calling a friend instead of opening a bottle of wine.”

It can be helpful to plan activities that naturally discourage alcohol use, like going to a fitness class or museum with a friend or hosting a game night with non-drinking buddies. And then the social support is huge: your family members, your online communities.

First Published: December 29, 2024, 10:30 a.m.

Updated: December 29, 2024, 6:00 p.m.