Whatever happened to the Zika virus?

The virus, mostly spread by mosquitoes, triggered alarming headlines in 2015-16 as cases climbed throughout South America, the Caribbean and South Florida — leaving hundreds of newborns with severe birth defects in its wake. The National Institutes of Health called it a pandemic.

But when mosquito season returned in 2017, Zika had largely fizzled.

In addition to dramatic drops in Pan American countries, the number of reported symptomatic cases in the U.S. plummeted from 5,102 in 2016 to 185 in 2017. In Pennsylvania, the number dropped from 175 symptomatic cases in 2016 to 4 in 2017 — likely all acquired when people were traveling abroad in affected areas. Allegheny County has not confirmed a new case of Zika since January.

A British study last summer predicted the virus would burn itself out — meaning enough people would develop antibodies against Zika to stem its spread — in three years. It hasn’t disappeared, but reported cases this year are far down.

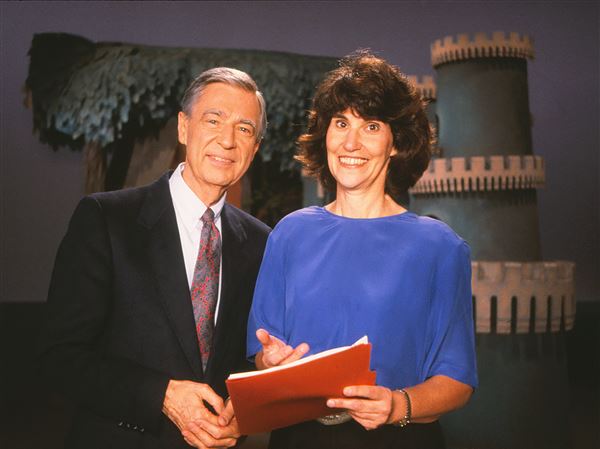

Despite the trend, concern remains, especially for pregnant women, said Kristen Mertz, a medical epidemiologist at the Allegheny County Health Department. Infected women are 20 times more likely to have children with deformities than women without Zika, according to a CDC report.

The fact that the virus infected fetuses signaled to Carolyn Coyne, a University of Pittsburgh researcher who studies immunology, that “something is different about Zika.”

To harm the fetus, the Zika virus must cross the placental barrier that separates the mother and the fetus. Most viruses are unable to do that, she said, and scientists still don’t know how it happens.

A study published Monday in the PNAS journal by Pitt and UPMC researchers shows advancements in understanding how Zika crosses this barrier.

But first the team had to create a new lab model of the placenta.

“Lab models of the human placenta have always been lacking,” said Ms. Coyne, an associate professor in the Department of Pediatrics at UPMC who co-authored the study. She said that this is because the placenta is a very complicated organ.

Earlier work primarily used flat cell line models that didn’t account for the movement of blood and other shear forces that occur in the human body, particularly in the placenta.

“In the human body, our cells are not static,” said Ms. Coyne, who holds a Ph.D. in pharmacology and completed her post-doctoral study in microbiology. “Cells in the lab respond very differently when you expose them to these shear forces.”

Using the new model, researchers studied Zika infection during the second trimester, an earlier stage of pregnancy than they’d looked at before, when infection would more likely cause fetal disease.

Earlier stages of pregnancy are more important to study because the risks of infection are greater then, Ms. Coyne said. This could be because the fetuses are more vulnerable, or because the placental barrier is weaker, she said.

In 2016, according to a CDC report, 10 percent of women in the U.S. with a confirmed Zika infection had a baby with a birth defect. For women who were infected during their first trimester, 15 percent had children with birth defects.

Previous studies by Pitt researchers demonstrated that, in later stages of pregnancy, cells on the placental barrier continuously release type III interferon, an immune cell that helps to prevent infection by Zika. The research team wondered: did that happen earlier in pregnancy? If not, the absence of that type of immune cell could be a weakness in the placental barrier that allowed Zika virus to infect the fetus, Ms. Coyne said.

The study found that during the second trimester, the placenta does continuously release type III interferon, which rules out the hypothesis.

Ms. Coyne said that her team’s work is to create a road map of how Zika crosses the placental barrier. This finding rules out one route, but “there must be other roads,” and the lab model of the placenta that Ms. Coyne and her colleagues developed will be vital in studying them.

Dr. Mertz said that her greatest concern is possible future risks to infants with mothers infected by Zika: “We still don’t know the long-term impacts.”

She said that she doesn’t know whether Zika is coming back again, and she doesn’t have a complete explanation for the sudden drop in infection, but immunity plays a role.

After an individual is infected with Zika, they develop lifelong immunity — meaning that they cannot become infected or transmit the disease again, Dr. Mertz said. In areas with high rates of infection, this means that there are fewer individuals susceptible to the virus.

Ms. Coyne said that the importance of the PNAS study goes beyond Zika, because it reveals new information about how the placental barrier works.

Going forward, she has new questions on her mind: If type III interferons are being continuously released throughout pregnancy, what impact does this have on the mother? And how do these findings apply to other viruses that cross the placental barrier?

Catherine Cray, a rising junior at Yale University, is a former Post-Gazette summer intern. Health@post-gazette.com.

First Published: August 7, 2017, 7:14 p.m.