He first became immersed in Jewish worship as a boy soprano in his synagogue choir. By his mid-teens, he was leading that choir as his voice evolved into the resonant tenor that in recent days has been heard throughout the world — a voice whose trembling yet resolute lament expressed and soothed the broken heart of his newly adopted Pittsburgh.

Rabbi Hazzan Jeffrey Myers — the two ordained titles refer to his dual role as spiritual teacher and worship song leader — spent decades in quiet ministry in Long Island, N.Y.; New Jersey and now Pittsburgh, comfortable in front of his congregation but little known outside the circles of his Jewish denomination.

Then came the horrific morning of Oct. 27, when a heavily armed gunman who police say had been pouring anti-Jewish hatred into the internet turned words into deeds, beginning a murderous rampage in the Tree of Life / Or L’Simcha synagogue building during morning Sabbath services.

All three congregations sharing the Squirrel Hill space — Congregation Dor Hadash, New Light Congregation and the merged Tree of Life congregation, which Rabbi Myers has led for just over a year — lost members.

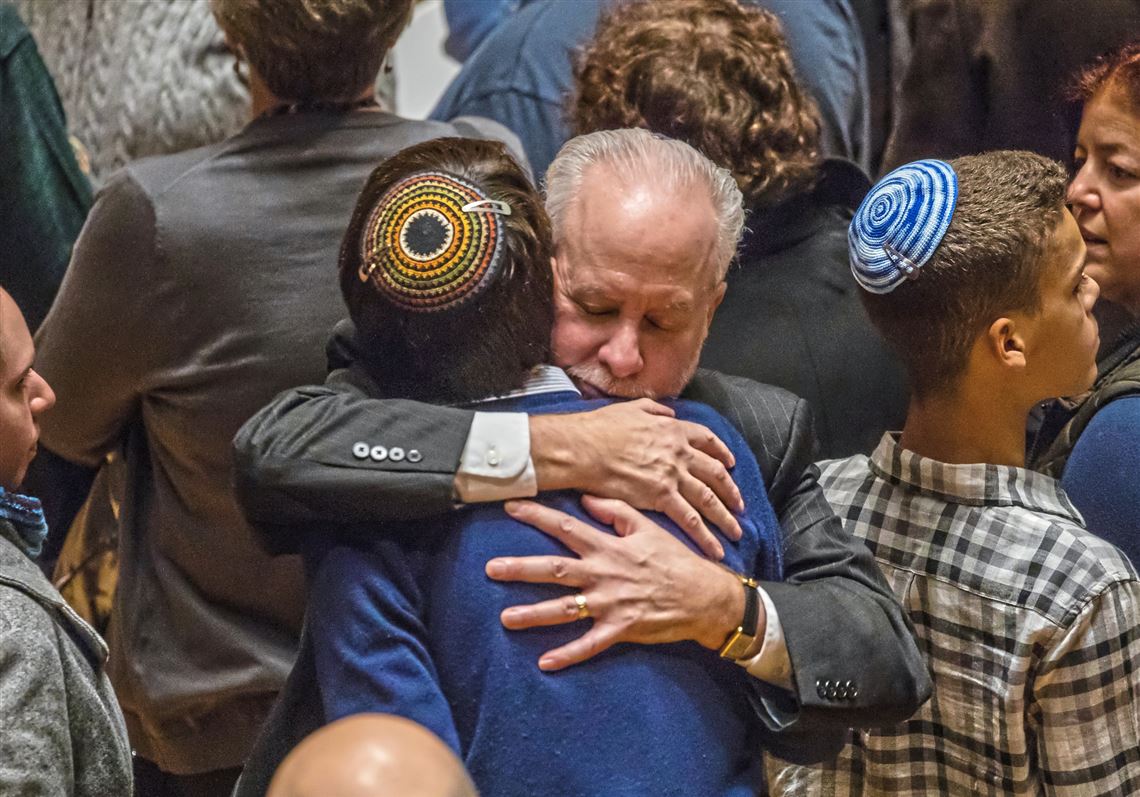

Three sets of rabbis, lay leaders and loved ones spent the ensuing days reeling from shock and grief, planning funerals and consoling the bereaved who turned out by the thousands at vigils and memorials.

In many ways, Rabbi Myers became the face of the tragedy, beginning with the stunning photo seen worldwide, showing him still in his prayer shawl as a police officer rushes him to safety during the shooting rampage.

He appeared again and again in public in the ensuing days, willingly giving live interviews to morning news programs, physically being pulled into other network TV interviews and hosting the controversial visit of President Donald Trump and the first family to the violated synagogue.

“America’s rabbi,” was how Tree of Life’s Rabbi Emeritus Alvin Berkun described his successor’s gracious response. “He handled himself very, very well.”

Rabbi Myers said he has been willing to step forward partly in gratitude to Pittsburgh in general for its support, and to its police officers in particular who rescued him and others at risk to their lives. Six officers were injured, four by gunfire.

“If it wasn’t for Pittsburgh’s finest, I wouldn’t be standing here, addressing you today,” he told a Friday rally for peace at Point State Park.

Rabbi Myers also wants to help Americans learn from this calamity.

“It’s not about me,” he said. “It’s about hate. How tragic it was that people without an ounce of hate had hate inflicted on them.”

“This can be a watershed moment in our country if people choose to because we have a choice every minute of the day what comes out of our mouths,” he continued. “As easily as we spew hate, we also can spew love. To me, if that can begin to happen, then the deaths of these 11 people will not be in vain. If there’s no change whatever, then it confirms our worst fears about the path we’re heading down, and it’s the wrong path.”

And although the New Jersey native has been in town barely a year, Rabbi Myers’ voice also became a voice of Pittsburgh — gracious, consoling, heartbroken and resolute.

Less than 36 hours after the murders, he chanted the El Maleh Rachamim, the traditional Jewish mourner’s prayer, at a community vigil before thousands at Soldiers & Sailors Memorial Hall and Museum. His voice soared, echoed, quivered but never cracked. And he chanted the lament again and again at funerals over the coming days.

Each time, Rabbi Myers added a line commending the victims as martyrs, using a line he had never used at a funeral before and that is rarely heard on American soil outside of Holocaust commemorations: “They gave their lives in the sanctification of your holy name,” he sang in Hebrew.

“Each time I’ve done the El Maleh, I felt it takes a piece of my soul,” he said.

After the final funeral he conducted, for 97-year-old Rose Mallinger, as the pallbearers were bringing the casket to the hearse, he followed beyond, reciting biblical Psalms as is the custom. He found a bench by a garden.

“I just sat down and lost it,” he said. “I’m a human. I lost it. I’m not sure how long I was there. I was partly embarrassed — how could I not be, because I’m the rabbi? But I’ve been foisted into this. I didn’t elect for it. And it’s sometimes that burden can be unbearable. Your shoulders can only carry so much weight. And people were really kind to just walk by and put their hand on my shoulders for a moment. I just had to continue my grieving, because I’m a mourner, too.”

Yet he did get up. That was a week ago Friday, and there was more to be done. Sundown brought the first Shabbat since the massacre. Tree of Life met in a chapel space offered by Rodef Shalom Congregation.

He led the prayers before a crowd greatly swelled by well-wishers, and Rabbi Myers could find humor in the unusual situation of having so many attendees that people had to share prayer books.

He mixed biblical quotations with an earthy paraphrase of the Cowardly Lion of “The Wizard of Oz”: “Not now, not no how, not never. They ain’t chasing us out of our house!”

He has spending much of his time now with the congregation, tapering back his public appearances, as he tends to individuals’ emotional and spiritual wounds.

Rabbi Myers, 62, wearing a neat brown suit and a yarmulke with a Pirates “P” logo in a nod to his adopted city, spoke in an interview at the kosher Dunkin Donuts in the heart of Squirrel Hill, the diverse neighborhood that is the hub of Jewish Pittsburgh.

He likes to patronize the shop for its accommodation of those who observe kosher dietary rules, such as himself. He also began coming here regularly in recent days by necessity: with his own office inaccessible while Tree of Life was cordoned off as a crime scene, he set up shop each day at a high table at Dunkin Donuts, where he fielded phone calls and frequent condolences from fellow customers.

He was born in Newark, N.J., and raised in the nearby town of Roselle. His father was a lawyer turned prosecutor turned judge, his mother a homemaker before returning to the workforce when the children got older.

Rabbi Myers was drawn to synagogue worship early, mentored by an older hazzan, or cantor. One year, shortly before the high holidays of Rosh Hashana and Yom Kippur — red-letter dates for synagogue worship — the hazzan suffered a stroke.

“Part of it paralyzed his vocal chords, which was a painful thing,” Rabbi Myers recalled, causing him to ask, not for the last time: “God, really?”

Members of the choir met and chose young Jeffrey to take over. No one else knew the synagogue’s unique repertoire so well.

“I was a kid,” he said. “I was 15, I think. I can say I just somehow had a natural affinity for it. I knew all four parts of every piece, memorized.”

If he had any nervous butterflies, they dispersed whenever the music began. Then he would inhabit it.

He continued to lead worship at his synagogue through high school and beyond. He started a pre-med course of study at Rutgers University, but his heart wasn’t in it. He majored in Jewish studies instead.

He planned to become a rabbi, but with his gifts for music and worship leading, was steered toward years of study at Jewish Theological Seminary in New York City to become a cantor, or hazzan in Hebrew. Rabbis and hazzans are distinct types of ordained ministers.

He became a cantor in the Conservative movement of Judaism, long considered a moderate stream of Judaism, adhering to religious law in the context of modern circumstances and learning.

He led worship as well as education programs at Conservative synagogues in the greater New York region for decades.

More recently, he studied for ordination as a rabbi, partly to have more prospects for work that could sustain his family. Like many historic religious denominations, Conservative Judaism has seen congregations shrinking, merging and often unable to afford more than one clergy member on staff.

The dual ordination enabled him to follow opportunity to Pittsburgh and become rabbi and hazzan at one of those merged congregations, Tree of LIfe / Or L’Simcha. Under what’s known as a “metropolitan” model, that congregation further opened its doors to New Light and Dor Hadash, sharing in space and activities.

“I’d never been to Pittsburgh, ever,” he said, other than maybe an airport layover. He and his wife live near the synagogue with their adult son and keep in daily contact with their adult daughter, a teacher in New Jersey.

Until Oct. 27, his work was mainly that of getting to know his small but dedicated congregation. In a recent blog post about the lull of activities following a series of holy days, he urged members to think of new ways to get involved: maybe suggest an adult-education class, come more regularly for daily prayer, even consider a bar or bat mizvah if one never had such a ceremony at the usual age of 13.

“I am your Jewish tour guide on the journey called life,” he wrote. “How might I make your journey more meaningful? Call me.”

That tour has an unexpected new itinerary.

Now he has begun helping those members wrestle with the deepest questions of their lives, going “literally one by one to each congregant. ‘How are you doing, what do you need?’ There are no doubt a lot of emotional wounds.”

As he tends to his own, he draws on the ancient prayers, praises and laments in the biblical Psalms.

“All of us have those moments of raw emotions,” he said, “and you say, well, how did the Psalmist deal with those raw emotions? What guidance can I get that can help me move forward? I can’t say that they’re infallible, that they always give me what I need, but the vast majority of time they have, so I keep going back to them every time I need to refill my tank.

“I don’t blame God,” he added. “To me, God’s not the one sitting in some divine control room, pushing buttons and levers and switches and saying, ‘Now I’m going to make this happen.’

“My God is someone I turn to at a time like this to say, ‘God, give me strength to get through this, what are the right words to say when I don’t know what I should say?’”

He doesn’t question why God would create a man who one day would be the killer who invaded his sanctuary.

“All human beings have choices,” he said. “This was a choice this person made. I don’t use his name. I won’t use his name. To use a name gives a person an infamy that is not deserved. One day, he’ll have to answer to God. Yes, of course, the American people and the American justice system, but also to God one day.”

Three days after the massacre, Rabbi Myers hosted the U.S. president and his family at Tree of Life.

The visit was controversial, and some in Pittsburgh said Mr. Trump was unwelcome so soon after the tragedy, given that people still were grieving and the presidential motorcade was blocking their way to console families sitting shiva.

And many protested the anti-immigrant rhetoric the president had been voicing in pre-midterm campaign speeches.

While the synagogue gunman depicted Mr. Trump as a tool of Jews, he also voiced hostility to the same groups of foreigners that the president has, such as refugees and the Central American migrant “caravan.”

Rabbi Myers said he got hate mail amid a “whole range of responses” to his agreeing to host Mr. Trump and his using the visit to call in general for an end to hate speech.

The rabbi took his cue from a Torah passage that he said was scheduled but never read Oct. 27 at Tree of Life, of how the biblical Abraham and Sarah rushed to provide hospitality to three strangers.

“Jewish tradition teaches the commandment to be hospitable to all guests,” he said. “So I was hospitable to the president and the first lady because they were my guests.”

They did not visit the rooms where worshippers were murdered. They did visit Tree of Life’s unscathed main sanctuary, which is only used on major occasions and was vacant Oct. 27.

“The president put his hand on my shoulder and said, ‘Rabbi Myers, how are you doing,’ accent on you,” he said.

It was a compassionate side of the president, he said, that America doesn’t normally get to see.

So Rabbi Myers told what he has told publicly elsewhere, how he and others thought the first gunshot was the sound of a falling coat rack, and when they realized what was happening, he and others closer to the front of the chapel escaped through a door to where they could try to get outside or hide in other rooms.

He returned in hopes of helping rescue the eight hiding in the back of the chapel, but by then the gunman was approaching, and Rabbi Myers hid inside an upstairs bathroom, called 911 and held the door tightly until he eventually was rescued by police. But in that time he could hear the gunfire that would kill seven of those congregants and wound the eighth.

“After sharing this story, much to the horror of the entire [first] family, I then shared my concerns with the president about hate speech, and that hate speech leads to hate actions, such as the massacre in my congregation,” Rabbi Myers said.

“I’ve never made my political persuasion known. That’s my business,” he said. “But this isn’t about politics. Hate doesn’t know red or blue, or purple.”

The group then lit 11 candles in the back of the main sanctuary in memory of the victims and then Rabbi Myers chanted the same memorial prayer he has sung at each funeral and vigil. They then paid tribute at the memorial to the 11 outside the building.

“The only way to change the world is to show love, not hate,” he said. “Hate can never beat hate. And that has been the guiding force for me throughout that.”

In hatred, “you don’t get how you become part of the problem, not part of the solution. It’s corrosive. It rots you from the core out. So you reach a point where you don’t even know you’re showing hate. It takes hold of you.”

At one point in the interview, he paused, looking through the window diagonally across Shady Avenue to the Starbucks, which had heart signs on its windows, with Jewish stars inside them. He hadn’t noticed them before.

“Wow,” he said. “The love of Pittsburgh has been beyond measure. It makes me speechless. Obviously I’ve never experienced this horror [before], and God willing no house of worship ever experiences this again, but it leaves me speechless, yet hopeful, that love will yet win out.”

Peter Smith: petersmith@post-gazette.com or 412-263-1416; Twitter @PG_PeterSmith.

First Published: November 12, 2018, 10:45 a.m.