WASHINGTON — He wanted to put the Pittsburgh Diocese on the map.

That’s what Donald Wuerl, now a cardinal, said when he became bishop of the diocese that baptized him and shaped his earliest views of what it meant to be faithful, to be moral, to be Roman Catholic, and to be good.

Thirty years later, everyone is talking about the diocese, but not for any of the reasons he envisioned. Pittsburgh is on the map now because of a sex scandal involving 99 priests accused of abusing hundreds of young parishioners over seven decades.

Cardinal Wuerl had become known as a gutsy but introverted leader who saved the diocese from financial disaster, elevated women in the church, created a well-read adult catechism, withstood downturns in Catholic school enrollment, held his flock together through tumultuous parish mergers, engaged with parishioners in ways predecessors had not, and handled delicate assignments.

Now, though, the cardinal is facing a crisis after a grand jury report revealed a horrifying culture of sexual abuse partly under his watch as bishop of Pittsburgh, where priests are accused of unthinkable abuses — mostly against young boys who were raped, groped, photographed nude, whipped and otherwise abused by men they called “father.”

Cardinal Wuerl, now archbishop of Washington, was not implicated in the abuse itself but is facing intense criticism for not doing enough to protect his flock or to warn other dioceses where wayward priests were reassigned.

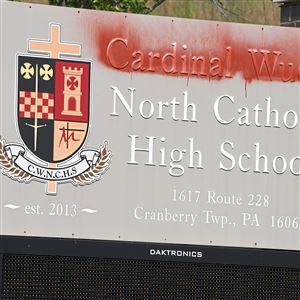

Catholics and others across the country are calling for his resignation while locally people have expressed their derision by vandalizing a sign at Cardinal Wuerl North Catholic High School and circulating petitions calling for the school’s renaming, which the diocese swiftly approved on Wednesday with the agreement of the cardinal and Bishop Zubik.

“It is time to restore justice to the wounded and regain the trust of the faithful by removing all tainted clergy from positions of leadership in the church,” wrote organizers of one online petition drive that has collected more than 60,000 signatures.

Also last week, the cardinal canceled a planned trip to Ireland during Pope Francis’ visit where he was to deliver a speech at the World Meeting of Families, and Ave Maria Press indefinitely postponed the planned October release of his latest book, “What Do You Want to Know: A Pastor’s Response.”

That’s just the start of the fallout from a scathing grand jury report that accused Cardinal Wuerl of allowing a known child molester to remain in ministry, reinstating another after he received psychiatric treatment for pedophilia, presiding over a settlement agreement that required two brothers to keep quiet about their abuse by a third priest, and arranging payments from the diocese for that priest after his release from prison.

Those allegations, which emerged in the scathing Pennsylvania grand jury report issued Aug. 14, describe the same church leader who cultivated a public image as a reformer who prided himself on his work to right the church’s course when it came to sex abuse like the kind that plagued Boston, where diocese leaders were more interested in protecting clergy from prosecution than seeking justice or care for victims.

When sex abuse cases did arise in the Diocese of Pittsburgh — the first just a few months after he became bishop — Cardinal Wuerl met face-to-face with victims, led the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops to create guidelines for accountability and prevention of future abuse, launched a Diocesan Review Board to address accusations, and risked his future in church leadership by fighting an order from the Vatican’s highest court to reinstate the Rev. Anthony Cipolla after he was accused of molestation. Earlier this summer Cardinal Wuerl — he was elevated to the College of Cardinals in 2010 — proposed that the conference instate a panel to investigate rumors of sexual misconduct by its own members.

Is Cardinal Wuerl a villain who turned his head while children were abused? Or is he a hero whose courage in fighting the Vatican emboldened other bishops to remove suspected abusers from their parishes?

Timothy Bendig believes he could be both. Mr. Bendig was one of three boys who have said they were abused by then-Father Cipolla in the 1970s and 1980s.

Cardinal Wuerl “fought to have this perpetrator removed, and that gave all the bishops the strength and the power to remove bad priests,” Mr. Bendig said.

For that, he will always be grateful.

But, he said, it would be unforgivable if the allegations laid out in the grand jury report turn out to be true.

“Do I think he should be held accountable for any criminal wrongdoing after my case? Yes. If there was any cover-up, he should step down,” said Mr. Bendig, now 49. “At this point I don’t know if there’s credible information to say that. Because of what he did for me and how he fought Rome to get this perpetrator removed, how can I personally say he did wrong when we don’t know?”

Mr. Bendig said Father Cipolla molested him numerous times when he was 12 to 17. He said he was aware that other priests in the diocese also were molesting boys and said Father Cipolla protected him from their abuses.

“I remember Cipolla telling them, ‘Don’t touch him. He’s mine,’” Mr. Bendig recalled in an interview.

Mr. Bendig ultimately sued the diocese and received a settlement in 1993 that he described as sizable although he declined to disclose the amount.

What he really wants now is the one thing he can’t have: an apology to his mother, Rita, who died in 2015 still feeling guilty that she had allowed Father Cipolla into her son’s life.

Michael Sean Winters, who writes for the National Catholic Reporter, said Cardinal Wuerl made mistakes, but that those should be viewed in the wider context of the reforms he achieved, the courage he had as a young bishop fighting the Vatican over Father Cipolla’s status, and his later mandate that abuse within the church be reported to civil authorities.

Wuerl spokesman Ed McFadden said his boss took the lead on an issue that other bishops were ignoring. His effort was imperfect,but it was more than anyone else in the church was doing, Mr. McFadden said.

Academics who study the church struggle to reconcile the contents of the grand jury report with the reputation of the man behind the Dallas Charter.

“I know for a fact that in Rome he has been a strong advocate for measures to tighten up procedures within the church for handling abuse cases, and there’s the well-known example of Father Cipolla where it’s quite clear he even bucked the Vatican to do what was the right thing. I respect him for all those efforts,” said Stephen F. Schenck of the Institute for Policy Research and Catholic Studies at The Catholic University of America. “On the other hand, I have to say that from the point of these awful allegations … I’m dumbfounded.”

Mr. McFadden said Vatican procedures made it very difficult for bishops to remove priests at the time.

That became easier after the passage of the Charter for the Protection of Children and Young People — better known as the Dallas Charter — which Cardinal Wuerl persuaded the U.S. Conference of Bishops to pass in 2002. It set standards for responses to allegations that now include cooperation with police, discipline for offenders and help for victims.

The Diocese of Washington declined to make Cardinal Wuerl available for comment for this story, but in an interview last week with Fox 5 Washington he defended his response to sexual abuse allegations in Pittsburgh.

“How do you deal with an allegation? Remember, when an allegation comes forward that allegation oftentimes ends up being one word against another,” the cardinal told Fox 5. “I think I did everything I could” including establishing an internal review board to investigate allegations.

That’s not how grand jurors saw it.

“Priests were raping little boys and girls, and the men of God who were responsible for them not only did nothing; they hid it all,” they wrote in their report.

Cardinal Wuerl told Fox 5 that isn’t true, but he acknowledged that the church has to be better at addressing sexual abuse by clergy.

His defenders say he responded in accordance with standards of the time that called for removing offenders from the situation, providing counseling to them and protecting victims from the further trauma of police inquiries. Wuerl allies say the standards of today are much different and, likewise, the church’s response to accusations have evolved.

Judy Jones doesn’t buy that. Sexual abuse of children has always been morally and criminally reprehensible, she said in a phone interview from her home in St. Louis, where she is the Midwest Regional Leader of SNAP, the Survivors Network of Those Abused by Priests.

“They keep saying, ‘We are learning.’ They’ve always known it was wrong to sexually abuse a child.”

She holds Cardinal Wuerl personally responsible for the abuses in Pittsburgh in the ’80s and ’90s. His work on the Cipolla case and the Dallas Charter shouldn’t absolve him of responsibility, she said.

Mr. McFadden said he understands the outrage and that Cardinal Wuerl is a natural target of it because he is the most senior church leader named in the report.

“The anger is righteous. People are devastated, and rightly so,” the Wuerl spokesman said. “It goes to breaches of trust in the most painful way possible because you have men that you entrust in some cases literally to the salvation of soul who would prey on children and breach that trust in just an incredibly ghastly, horrendous way.”

But, he said, the abuses would have been worse if not for the efforts of Cardinal Wuerl.

“We have a man who, in my mind, did something during his years in Pittsburgh that virtually no other bishop in America was undertaking at the time,” Mr. McFadden said. “And his record reflects, by and large, that he was successful in doing what he set out to do, which was remove priests from the ministry so that they could not harm children again. It’s that simple.”

By his count, 32 names of suspected abusers came to light on Cardinal Wuerl’s watch.

Fourteen of those cases involved priests who either had died or who had already been removed from the ministry by the time Cardinal Wuerl arrived, Mr. McFadden said. Cardinal Wuerl addressed the other 18 cases either by removing them from ministry entirely or restricting their roles, he said. In a few of those cases, which he said the cardinal now regrets, offenders were returned to the ministry.

“There are cases that should have been done differently and we absolutely agree with that. His eminence has made clear that there were mistakes,” Mr. McFadden said.

One of those mistakes was in the well-publicized case of the Rev. Ernest Paone, a known serial pedophile whose transfer to Nevada was approved by Cardinal Wuerl. Mr. McFadden said the late Father Paone had been living in California for 25 years by then and that old files were so disorganized that Cardinal Wuerl hadn’t seen reports of his abuse until 1994 when a new accusation surfaced, which he brought to the attention of bishops in California and Nevada.

Critics say the cardinal fell far short of his responsibilities in Pittsburgh. Catholic conservative commentator Hugh Hewitt called him “the most skilled co-conspirator” in the effort to cover up the abuses in Pittsburgh, that rather than advance church reforms he undermined them, and that now he should step down.

The cardinal has said that he will not resign although, technically, he already has. He did it almost three years ago on his 75th birthday as all Catholic bishops are required to do. It’s up to the pope when to accept it. Cardinals in good health often continue serving until age 80 when they can no longer vote at conclave.

Pope Francis’ acceptance of his resignation — whether now or years from now — will end a long career in the church that officially began with ordination in 1966, although young Don Wuerl had his eyes on the altar years before that when he would preside over pretend Masses for his siblings in the family home in Mount Washington.

He attended St. Gregory Catholic Seminary in Cincinnati, the Theological College at Catholic University and the Pontifical North American College in Rome. He earned his doctorate in theology at the Pontifical University of St. Thomas.

He was a parish priest at St. Rosalia in Greenfield and secretary to Cardinal John Wright, an influential mentor in Rome, where the young Father Wuerl gained a reputation as a thoughtful, organized, and self-disciplined workhorse whose potential demanded that he serve more than the simple pastoral role he desired. He was bound from the beginning for a leadership role, but first he would return briefly to Pittsburgh to serve as rector at St. Paul Seminary.

In 1985 he was sent to Seattle — and into a firestorm that would test his leadership and diplomatic skills. Pope John Paul II — one of three popes Cardinal Wuerl developed personal relationships with — named him auxiliary bishop and ordered the sitting archbishop, Raymond Hunthausen, to surrender some of his power to him.

Outrage ensued.

Papal critics assumed Bishop Wuerl was sent to humiliate and crack down the archbishop, whose liberal approaches to homosexuality, general absolution, annulment and contraception offended conservative church leaders.

People expected a power struggle, but the mild-mannered Bishop Wuerl didn’t give it to them. While Seattle parishioners were outraged that their archbishop had to cede power to him, the specially appointed auxiliary bishop made little use of his authority, preferring to gain buy-in while avoiding sharp rhetoric and stringent edicts, according to a Seattle Post-Intelligencer editorial written in 1987 as his time in Seattle wound down.

By then, the situation had become unworkable. So Pope John Paul restored the archbishop’s full authority and soon after made Bishop Wuerl bishop of Pittsburgh, where his challenges included merging parochial schools, closing churches, turning around a spending deficit and engaging lay workers in the church.

He faced criticism for extravagance after his decision to live in a $2 million, 39-room Shadyside mansion owned by the diocese instead of choosing to live more austerely in a small apartment at St. Paul Seminary as his successor, Bishop David Zubik, now does. His four predecessors also lived in the mansion, which has since been sold for $2 million.

In 2006, it was on to the District of Columbia, where, as archbishop of Washington, one of his first big tasks was to host a visit by Pope Benedict XVI. Archbishop Wuerl succeeded the affable Cardinal Theodore McCarrick, who — although it had not yet come to light — had been sexually abusing young priests and seminarians.

Cardinal McCarrick was removed from public service in June. In July, Pope Francis accepted his resignation from the College of Cardinals.

“The news regarding Archbishop McCarrick was a great shock to our Church in Washington,” Cardinal Wuerl told The Catholic Standard, the newspaper for the archdiocese. “There is understandable anger, both on a personal level due to the charges, but also more broadly at the Church. Our faithful have lived through such scandals before, and they are demanding accountability.”

Washington Bureau Chief Tracie Mauriello: tmauriello@post-gazette.com; 703-996-9292 or on Twitter @pgPoliTweets.

First Published: August 27, 2018, 10:57 a.m.