The 40th Statewide Investigating Grand Jury identified more than 1,000 child victims from more than 300 abusive priests across 54 of Pennsylvania's 67 counties.

Still, that's not all of it.

"We believe that the real number of children whose records were lost, or who were afraid ever to come forward is in the thousands," they wrote.

In a scathing introduction that provides excruciating detail of only a handful of instances of abuse, the introduction explains the grand jury's purpose, its findings and its ultimate recommendations.

"Most of the victims were boys; but there were girls, too. Some were teens; many were pre-pubescent. Some were manipulated with alcohol or pornography. Some were made to masturbate their assailants, or were groped by them. Some were raped orally, some vaginally, some anally. But all of them were brushed aside, in every part of the state, by church leaders who preferred to protect the abusers and their institution above all."

The grand jury said it laments that in nearly every instance, the abuse is too far removed to merit criminal charges.

"This report is our only recourse. We are going to name their names, and describe what they did -- both the sex offenders and those who concealed them. We are going to shine a light on their conduct, because that is what the victims deserve. And we are going to make our recommendations for how the laws should change so that maybe no one will have to conduct another inquiry like this one."

Throughout its proceedings, the grand jury found that in each diocese, almost the same pattern emerged -- so much so that the documents obtained from the dioceses’ "secret archives" were susceptible to behavioral analysis by the FBI.

The grand jury heard testimony from special agents who identified a series of practices that regularly appeared in the files they analyzed.

"It's like a playbook for concealing the truth," they wrote. "The main thing was not to help children, but to avoid 'scandal.'

"That is not our word, but theirs, it appears over and over again in the documents we recovered."

Although the grand jury excoriates the abusive priests, it is no less hard on the bishops who oversaw them, ignored the abuse, or willingly moved them from parish to parish.

In Erie, for example, after a priest confessed to anal and oral rape of at least 15 boys, the bishop later met with him to "commend him as 'a person of candor and sincerity’ and to compliment him 'for the progress he has made' in controlling his 'addiction.'"

When that priest was finally removed from the priesthood years later, the bishop ordered that the parish not say why.

"What we can say, though, is that despite some institutional reform, individual leaders of the church have largely escaped public accountability. Priests were raping little boys and girls, and the men of God who were responsible for them not only did nothing; they hid it all," they wrote. "For decades, monsignors, auxiliary bishops, bishops, archbishops, cardinals have mostly been protected; many, including some named in this report, have been promoted. Until that changes we think it is too early to close the book on the Catholic Church sex scandal.”

The grand jury calls the historical record being created "highly important, for present and future purposes.”

"The thousands of victims of clergy child sex abuse in Pennsylvania deserve an accounting, to use as best they can to try to move on with their lives," it wrote. "And the citizens of Pennsylvania deserve an accounting as well, to help determine how best to make appropriate improvements in the law."

Among the recommendations by the grand jury:

• It urges the state Legislature to stop "shielding child sexual predators behind the criminal statute of limitations," and allow reports of abuse to be charged at any age and after any period of years.

• It urges the creation of a "civil window" for victims to be able to file lawsuits against their dioceses to recover damages.

• It seeks improvement to the mandated reporting laws, that, right now, require reporting of abuse that is "active."

"We think it's reasonable to expect one of the world's great religions, dedicated to the spiritual well-being of over a billion people, to find ways to organize itself so that the shepherds stop preying upon the flock," they wrote. "If it does nothing else, this report removes any remaining doubt that the failure to prevent abuse was a systemic failure, an institutional failure. There are things that the government can do to help. But we hope there will also be self-reflection within the church, and a deep commitment to creating a safer environment for its children."

At a Downtown news conference, Pittsburgh Bishop David Zubik expressed sorrow and apologized, saying the grand jury report spotlights "people who need to be heard, people who need to be healed."

"No one who has read it can be unaffected," Bishop Zubik said. He pledged to continue to meet "with any victim to apologize to them in person and in the name of the church."

Still, Bishop Zubik said he knew of no cover-ups in his three decades working largely with the Pittsburgh Diocese. He said Cardinal Donald Wuerl, a former Pittsburgh bishop noted at length in the report, "did a great deal to address the issue of child sexual abuse."

That emphasis continues, according to the bishop, who announced three additional steps Tuesday. He said the diocese has engaged an expert in the prevention and prosecution of child sexual abuse to review its practices; created a position to monitor clergy removed from ministry amid abuse claims; and will post online a list of 83 diocesan priests accused of child sexual abuse.

Some priests on the list are not named in the grand-jury report, Bishop Zubik said. Of 90 priests and religious brothers listed as Pittsburgh-area offenders in the report, 68 were priests in the Pittsburgh diocese, he said. Twenty-two were priests elsewhere or priests or brothers of religious orders, according to the bishop.

----

The grand jury report, which traces back seven decades and covers six Roman Catholic dioceses in Pennsylvania, is thought to be the widest, most-sweeping report of its kind in the country. Advocates and church leaders alike say they cannot recall any other multi-diocese investigations occurring in other states.

Its blistering results come at a tumultuous time for the church, which is roiling from revelations of abuse and cover-up both nationally and internationally. Retired Archbishop Theodore McCarrick of Washington resigned last month as cardinal after revelations that he sexually abused boys and exploited adult seminarians. A leading U.S. cardinal admits "grave moral failures of judgment on the part of church leaders" as bishops work on policies to discipline their own and protect budding priests amid growing #MeToo allegations in seminaries. Allegations of cover-ups by bishops have ranged from Buffalo, N.Y., to Chile to Australia.

In Pennsylvania, advocates will be watching closely to see if fallout from the report prompts state legislators to advance a bill to expand the statute of limitations in criminal and civil cases. While survivors have heralded such bills as a long overdue step toward closure, they have been blocked — usually after aggressive lobbying by the church or the insurance industry, both of which argue that a fresh onslaught of lawsuits could lead to their financial ruin.

The report’s release ensures that every Roman Catholic diocese in the state — and, therefore, every state legislator’s district — has now been scrutinized by an independent prosecutor.

The Archdiocese of Philadelphia has been the subject of three grand jury reports since 2003. And the Altoona-Johnstown diocese was examined in a 2016 report that found that hundreds of children had “fallen victim to child predators” tied to the church, and that church leaders did not always take adequate steps to protect them.

This latest report, which grew out of the Altoona-Johnstown investigation, covers the remaining six dioceses in the state: Pittsburgh, Allentown, Erie, Greensburg, Harrisburg and Scranton. Together, those six dioceses count more than 1.7 million Catholics — just over half of the state’s Catholic population, according to church estimates.

Attorney General Josh Shapiro’s office inherited this investigation from his predecessor, former Attorney General Kathleen Kane.

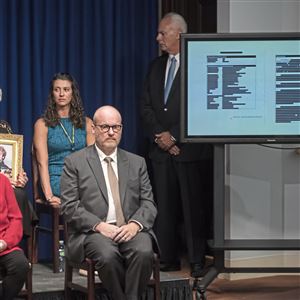

Over the course of two years, 23 grand jurors met regularly in private to hear testimony from dozens of victims, from perpetrators and, in one instance, from a bishop himself. By the time their work concluded in 2018, the grand jurors — with help from prosecutors — had produced a lengthy report detailing allegations of what Mr. Shapiro has described as widespread abuse and a “systemic cover-up” by church leaders.

The full report identifies 301 “predator priests” and describes efforts by some diocesan administrators to dissuade victims from speaking to police, pressure law enforcement to end investigations or conduct lackluster internal reviews.

But portions of the report also remain blocked from public view, because they are under a protective court seal. A group of roughly two dozen current and former clergy members have asked the state Supreme Court to shield the portions pertaining to them. They argue that those sections are inaccurate or unfairly tarnish their reputations, which are protected under the state constitution.

The high court agreed to release a redacted report while it weighs arguments about whether those sections of the report should eventually be released — or should remain forever shrouded in secrecy. Arguments in that case are scheduled for late September.

Mr. Shapiro has promised to continue to advocate for the release of the full report. He said last week, “Real justice will come about when the full report is released.”

Following are summaries of the findings on the dioceses.

Pittsburgh

The report lists 99 priests -- including one individual aspiring to be a priest -- who allegedly sexually abused minors in the Diocese of Pittsburgh.

According to the report, the abuse included "grooming and fondling of genitals and/or intimate body parts, as well as penetration of the vagina, mouth, or anus." Some bishops and other diocesan administrators in Pittsburgh, the report said, placed the priests in ministry even though they had knowledge of the conduct.

The report also found that in Pittsburgh, the diocese held discussions with lawyers regarding the sexual conduct of priests with children and made settlements with victims that prevented them from speaking out under the threat of some penalty.

Three cases -- those of Fathers Ernest Paone, George Zirwas and Richard Zula -- were detailed in the report as symbolizing the “wholesale institutional failure that endangered the welfare of children” in the Pittsburgh Diocese.

Father Paone, who served in the late 1950s and 1960s at five separate parishes and later served in California, was kept in active ministry for 41 years after the Diocese first learned that he was sexually assaulting children.

Greensburg

The grand jury found evidence that 20 priests and the late Monsignor Charles Guth sexually abused children in the Roman Catholic Diocese of Greensburg. Fourteen are deceased, six surviving priests were removed from the ministry and one left on his own.

Evidence showed that diocesan administrators including bishops “had knowledge of this conduct and regularly permitted priests to continue in the ministry after becoming aware that a child sexual abuse complaint had been made against them.”

The diocese made settlements with victims and had discussions with lawyers regarding the sexual abuse of children by its priests that often contained confidentiality agreements forbidding victims from speaking about such abuse under threat of some penalty, such as legal action to recover previously paid settlement funds.

Diocesan administrators, including bishops, dissuaded victims from reporting abuse to law enforcement.

The diocese regularly failed to independently investigate allegations of child sexual abuse in order to avoid scandal and possible civil and criminal liability on behalf of the diocese, the accused priest and diocesan leadership.

Investigations conducted by the diocese were “too often deficient or biased and did not result in reporting credible allegations of crimes against children to the proper authorities or otherwise faithfully respond to the abuse which was uncovered,” the report said.

Erie

At the Diocese of Erie, the grand jury found 41 offenders and discovered that two bishops at the diocese knew of ongoing abuse for years but did nothing to stop it, in some cases encouraging victims to stay quiet.

The report eviscerates Bishop Michael J. Murphy, who served at the diocese from 1982 to 1990, as well as Bishop Emeritus Donald W. Trautman, who led the diocese from 1990 to 2012, finding that both men worked to cover up allegations of sexual abuse and protect accused clergy.

The report highlights three example cases, including that of the Rev. Chester Gawronski.

In 1986, Bishop Murphy learned that Rev. Gawronski had “fondled and masturbated” a 13-to-14-year-old boy multiple times between 1976 and 1977 under the pretext of “showing the victim how to check for cancer,” according to the report.

That complaint was echoed by several other families in coming years, according to the report. Some families also reported that Rev. Gawronski had boys go skinny dipping on a camping trip and abused them during the trip.

In 1987, Rev. Gawronski himself provided church leadership with a list of 41 boys he had “had some contact with.” Rev. Gawronski put an asterisk next to 12 names, and confirmed he had performed “cancer checks” on those boys.

Rev. Gawronski was sent to Chicago for a psychological evaluation in 1987, then returned to his priestly duties. The complaints of sexual abuse continued after Bishop Trautman took over leadership of the diocese in 1990, with another victim coming forward in 1995, according to the report.

Yet in 1997, Bishop Trautman sent a letter to Rev. Gawronski lauding him for his “many acts of kindness” and “deep faith.” And in 2001, he granted Rev. Gawronski a five-year assignment as a chaplain for St. Mary’s Home in Erie.

Rev. Gawronski “withdrew from ministry” in February 2002, a month after the Boston Globe revealed widespread sexual abuse in the Archdiocese of Boston.

In a statement Tuesday, Bishop Trautman said the grand jury report “does not fully or accurately discuss my record as a bishop for 22 years dealing with clergy abuse.”

He said he removed 16 offenders from active ministry, established new guidelines for dealing with allegations of sexual abuse, and did his “best to correct the sin of sex abuse.”

“These are not the actions of a bishop trying to hide or mask pedophile priests to the detriment of children or victims of abuse,” he said.

Allentown

The Grand Jury report accuses 37 priests from the Archdiocese of Allentown of having sexual contact with minors, “including grooming and fondling of genitals and/or intimate body parts, as well as penetration . . .” The report says Archdiocesan administrators, including bishops, “had knowledge of this conduct” and yet placed priests in ministry after complaints had been made. The report also says the Diocese settled with an unspecified number victims, and it accuses officials of dissuading victims from contacting police.

In a response issued Tuesday, the Diocese said that it apologizes “to everyone who has been hurt by the past actions of some members of the clergy.”

“Most of the incidents in the report date back decades and the priests involved are either no longer in active ministry or deceased,” the statement said, outlining steps the Diocese has taken “to prevent abuse, and to provide support for victims and survivors.”

In a video statement posted online Tuesday, Bishop Alfred A. Schlert said “abuse is abhorrent and has no place in the church,” and said “perpetrators are no longer in active ministry.”

The report identifies all but one of the 37 priests accused of misconduct dating back at least five decades. The name of one priest, listed in what is called a “single victim group,” was redacted.

Francis Fromholzer

Francis J. Fromholzer is accused of sexually abusing two teenage girls during a trip in his car in the mid-1960’s, when he served as a teacher at Allentown Central Catholic High School.

One woman, identified in the report as Julianne, told the grand jury: “It was confusing because -- you were always told you were going to Hell if you let anybody touch you. But then you’ve got Father doing it.”

The second victim later tried to report Fromholzer’s actions to the school’s principal, Rev. Robert M. Forst, the report says. Forst allegedly responded by threatening to expel her. He then held a meeting with her father during which Forst called the allegations a “made-up story.” The report says the girl’s father believed she was lying, and subsequently slapped her and beat her with a belt buckle.

Julianne tried as an adult to report Fromholzer’s conduct, the report says. But two church officials rebuffed her efforts, she said. After the Boston Globe published an investigation of the Archdiocese in Boston in 2002, the report says, Julianne contacted local law enforcement. Fromholzer was never charged, but after the Diocese was made aware of her complaints, the report says, Fromholzer -- who had been working at a church grade school -- retired.

The report says that as Julianne made church officials aware of her allegations in the early 2000s, officials repeatedly sought to discredit her as a witness “with unrelated and irrelevant attacks on her family.” Those actions, the report says occurred on the watch of Bishop Edward Cullen, who, before his decade leading Allentown’s Diocese, was an administrator at the Philadelphia Archdiocese. The attempts to discredit Julianne were also sent to Schlert, Allentown’s current bishop, who at the time was a monsignor.

In 2009, the report says, under a new bishop, the Diocese formally reported the complaints against Fromholzer to the District Attorney.

Edward Graff

The report says the Rev. Edward R. Graff “raped scores of children” during his 45 years in ministry, most of which were served in Allentown. In one instance, the report says, he damaged one child’s back while raping him.

Yet Graff’s case, the report claims, “is an example of dioceses that minimized the criminal conduct of one of their priests, while secretly noting the significant danger the priest posed to the public.”

As evidence, the grand jury report showcased letters sent between former Bishop Thomas Welsh -- who led the Diocese from 1983 to 1997 -- and officials of dioceses in New Mexico and Texas, where Graff continued to practice ministry for 10 years after being allowed to retire from active priesthood.

Although none of the letters mention sexual abuse by Graff, the report said Welsh expressed concern about Graff -- who had long struggled with alcohol addiction -- and questioned his living arrangements and need to be supervised.

In one letter to church officials, Welsh is quoted as writing: “I know that you will appreciate the reasons for my concern, since the matter presents both your Congregation and the Diocese of Allentown with the potential of legal liability for anything untoward which may occur in the course of Father Graff’s ministry in Amarillo.”

The grand jury report said: “Welsh had the power to remove Graff’s faculties to minister in light of Graff’s known risk” but chose not to. It also said the language that church officials used to describe Graff “was much more consistent with language used in relation to predatory priests than a priest with a drinking problem.”

In October 2002, the report says, Graff was arrested in Briscoe County, Texas, for sexually abusing a 15-year-old boy. Graff died about a month later in prison, according to the report.

Michael Lawrence

The Rev. Michael Lawrence was suspected of “pedophilic behavior” when he was in seminary school in 1970, the grand jury report says, citing concerns raised in his student evaluation. He became a priest anyway, and in 1982, the report says, the father of a 12-year-old boy reported to church officials that Lawrence had sexually assaulted his son.

According to the report, Lawrence confessed to his actions when confronted by Monsignor Anthony Muntone. Citing letters allegedly written by Muntone, the grand jury report says that Lawrence was sent to a clergy treatment center in Downingtown, and that a “doctor” at that facility told Muntone “that the experience will not necessarily be a horrendous trauma for the boy.”

Less than two years later, the report says, Lawrence was given a job teaching high school religion classes.

In 1987 -- following repeated complaints from the boy’s father -- Lawrence was placed on sick leave and had his responsibilities curtailed, the report says. But he was not removed from service or forced to retire, the report said, adding: “In spite of a documented confession to child molestation, Bishops Joseph McShea, Thomas Welsh, and Edward Cullen permitted Lawrence to remain in active ministry within the Diocese.”

In 2002, the report says, as outraged swelled due to the priest sex abuse scandal in Boston, Lawrence retired. He died in April 2015.

Scranton

The grand jury identified 59 priests alleged to have sexually abused children in the Diocese of Scranton, which covers 11 counties in northeastern Pennsylvania. The report highlighted three of those priests as examples of the “wholesale institutional failure that endangered the welfare of children” across the state.

Rev. Robert N. Caparelli, who was ordained in 1964, is accused of abusing altar boys while serving as an assistant pastor at the parish of Most Precious Blood in Hazelton. In August 1968, a police officer sent a letter to then Bishop J. Carroll McCormick stating that Caparelli was “demoralizing” two brothers who were 11 and 12 years old – “in a manner that is not natural for any human that has all his proper faculties.”

Three days later, according to the report, the head pastor wrote to McCormick: “This problem is too big for me. It has grown into something that is unbelievable. In other words all that this gentleman writes is true... but there is so much that is missing, and all very, very serious.”

Caparelli later admitted, in McCormick’s words, that he was “acting too freely” with two altar boys, but insisted he didn’t do anything immoral. An internal diocesan memorandum dismissed the boys’ mother’s allegations. McCormick later sent Caparelli to another parish in Old Forge and in 1981 he was appointed head pastor of St. Vincent’s in Milford.

In future years, many additional victims would come forward. Caparelli later pleaded guilty to offenses against children and did prison time. While there, he tested HIV positive. He died in prison in December 1994.

“[Former Bishop James] Timlin and the Diocese of Scranton never fully disclosed the decades of knowledge and inaction that left children in danger and in contact with Caparelli,” the grand report states.

In October 1993, Timlin wrote to Caparelli’s sentencing judge, requesting that Caparelli be released from prison to a Catholic treatment facility. A copy of the letter was sent to Robert Mellow, president pro tempore of the state Senate.

The grand jury alleged that the Rev. Thomas D. Skotek, who was ordained in 1963, sexually assaulted and impregnated a minor female while serving as pastor of St. Casimir in Freeland in the 1980s. He then helped her get an abortion.

Records show that Timlin, the bishop, was aware of the situation, but seemed more concerned about Skotek’s wellbeing. In 1986, Timlin accepted Skotek’s resignation as pastor of St. Stanislaus Church in Hazelton and wrote: “This is a very difficult time in your life, and a realize how upset you. I too share your grief … With the help of God, who never abandons us and who is always near when we need him, this too will pass away, and all will be able to pick up and go on living.”

Skotek was sent to St. Luke’s Institute in Maryland for an evaluation. By January 1987, Skotek returned to being a priest in Wilkes-Barre and later served in Mocanaqua. He was not removed from active ministry until June 2002.

The grand jury also heard from a former high school student -- now 72 years old -- who said that the Rev. Joseph T. Hammond masturbated in front of him in 1961 and tried to fondle him inside the rectory at St. Leo the Great parish. The victim, identified only as Joe, said he was shocked: "He was right below God as far as I was concerned,” he testified. Hammond, who was ordained in 1931, continued in the ministry until his death in 1985. Investigators found no record in Hammond’s Diocesan file of a complaint made by Joe’s mother the day after the alleged incident. “The Grand Jury found Joe's testimony to be credible and this case demonstrative of the lasting effect of child sexual abuse,” the report states. “Joe sought justice at 72 years of age … While Hammond may be dead, the impact of his actions live on.”

The Diocese of Scranton responded to the grand jury report with a statement in which Bishop Joseph Bamber, who took over in 2010, offered his “deepest apologies to the victims who have suffered because of past actions and decisions made by trusted clergymen, to victims’ families, to the faithful of the Church, and to the community at large.”

“No one deserves to be confronted with the behavior described in the report,” the statement read. “Although painful to acknowledge, it is necessary to address such abuse in order to foster a time when no child is abused and no abuser is protected.”

The diocese said it cooperated with the grand jury probe and now adheres to a “strict zero tolerance policy” on child abuse. It said officials immediately notify law enforcement and remove accused priests from the community when allegations surface.

Harrisburg

Harrisburg Diocese priests groomed, fondled and raped victims, and several Diocesan administrators, including bishops, often dissuaded those who came forward from reporting the abuse to police, according to the report. Evidence also shows that settlements designed to silence victims were common.

Two Harrisburg priests and a church leader who the grand jury said was instrumental in the Diocese’s handling of sexual abuse allegations are among those who fought the report’s release. Their names are redacted. In all, 45 Harrisburg area priests are identified as abusers.

Rev. Augustine “Gus” Giella preyed on an entire Enhaut area family, abusing five sisters who belonged to St. John the Evangelist Church.

Giella’s abuse of one of those sisters was especially horrific. The fondling began when she was 18 months old and continued until she was 12. The grand jury concluded that Giella’s abuse could have been stopped much earlier if church leaders had acted on an early complaint.

Jesuit priest Arthur Long preyed on teenage girls, admitted to having sex with one and tried to marry another, but that didn’t stop church leaders from shuffling his assignments several times in the 1970s and 80s.

Monseigneur Hugh Overbaugh oversaw Long’s work, and in one letter regarding sexual abuse allegations against Long, he wrote, “While this documentation contains numerous complaints, we seldom if ever receive word of all the good which Father Long accomplished.”

One victim of Rev. Joseph Pease only came forward when he realized, 20 years after being assaulted, that his abuser was still in ministry and that the victim’s nephew was an altar server in his abuser’s church. That report came in 1995 and should have resulted in Pease’s referral to law enforcement. Instead, church leaders sent Pease for a psychological evaluation.

Almost 10 years later, church leaders who knew about the allegations against Pease allowed him to retire without defrocking him. Harrisburg Bishop Ronald Gainer affirmed his support for the abusive priest in a 2014 letter to the Vatican.

“I am not seeking the initiation of a trial, nor dismissal from the clerical state.” he wrote. Instead, he asked that Pease “be permitted to live out his remaining years in prayer and penance, without adding further anxiety or suffering to his situation, and without risking public knowledge of his crimes.”

In a statement Gainer released Tuesday in response to the grand jury’s report, he expresses sorrow over the grand jury’s findings and apologizes to survivors.

“I acknowledge the sinfulness of those who have harmed these survivors, as well as the action and inaction of those in Church leadership who failed to respond appropriately,” he wrote.

This story is based on reporting by Peter Smith, Liz Navratil, Angela Couloumbis, Jonathan D. Silver, Paula Reed Ward, David Templeton, Julian Routh, Shelly Bradbury and Torsten Ove.

First Published: August 14, 2018, 6:11 p.m.

Updated: August 14, 2018, 8:16 p.m.

•

•