When Charles Pearo was taking art history courses in Montreal and a professor would display an image of a painting by William Adolphe Bouguereau, "most of the students would laugh."

But Pearo would think: "It's beautiful."

That, in a nutshell, sums up the controversy that still swirls around the 19th-century French master, whose works are on display until October at the Frick Art & Historical Center in Point Breeze, in a show called "In the Studios of Paris: William Bouguereau and his American Students."

More than 100 years after his death, Bouguereau can still provoke diametrically opposed views. Either he was the one of the finest oil painters of all time, or he was an unimaginative, sentimental portrayer of hackneyed themes.

The show at the Frick, primarily designed to show Bouguereau's influence as a teacher of American students in Paris in the late 1800s, features 12 of his canvases, spanning the mythological, religious and French country themes that made him famous.

And no matter how much some may vilify him today, there is no doubt about how famous he was.

He was arguably the best-known painter in Paris in the last three decades of the 19th century, when Paris was the center of the art world.

"In his heyday, he really was the pinnacle of the French world of academic, official art. He was as famous and as well respected as the president of France at that point," said Eric Zafran, a curator from the Wadsworth Atheneum in Hartford who will give a talk on Bouguereau at the Frick at 7 p.m. tomorrow.

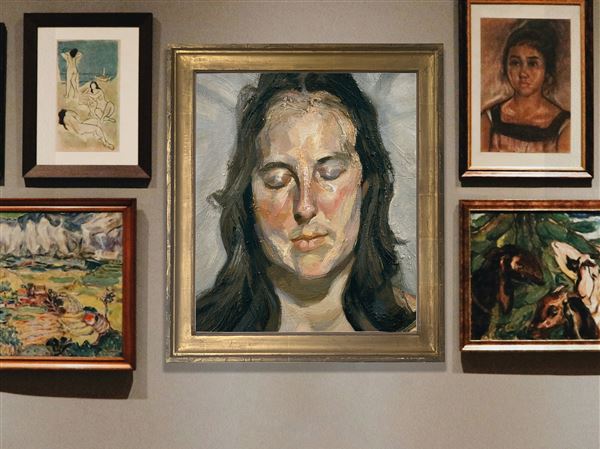

Sarah Hall, director of Curatorial Affairs for the Frick Art & Historical Center, stands with several Bouguereau paintings in the current exhibit.

Click photo for larger image.

Sarah Hall, director of Curatorial Affairs for the Frick Art & Historical Center, describes key aspects of Bouguereau's art and career:

Sarah Hall, director of Curatorial Affairs for the Frick Art & Historical Center, describes key aspects of Bouguereau's art and career: Why Bouguereau works are so popular at museums.

Why Bouguereau works are so popular at museums. Bouguereau's relationship with Elizabeth Gardner

Bouguereau's relationship with Elizabeth Gardner Bouguereau paintings in Pittsburgh

Bouguereau paintings in Pittsburgh

Artist specialized in properly cheeky cherubs

Artist specialized in properly cheeky cherubs

The Frick explores the idealized images of Bouguereau and his American students

The Frick explores the idealized images of Bouguereau and his American students

Bouguereau was a prize-winning exhibitor and judge at the annual Salon in Paris, then the most famous competitive art exhibition in the world.

In that role, he also became a major foe of Impressionist painters such as Claude Monet and Pierre Renoir, rejecting their work for display at the Salon. "He didn't lead some fiery pack against Impressionism," said Pearo, a Canadian art historian who did his doctoral work at the University of Pittsburgh. "He just didn't see it as good art."

In the ensuing decades, though, it was the Impressionists and other modern artists who took center stage, leaving academic lions such as Bouguereau and Englishman Sir Lawrence Alda-Tadema in the wings.

The denigration of Bouguereau's reputation began not long after his death in 1905. In a history of modern painting two years later, German critic Richard Muther wrote: "William Bouguereau, who industriously learnt all that can be assimilated by a man destitute of artistic feeling but possessing a cultured taste, reveals even more clearly in his feeble mawkishness, the fatal decline of the old schools of convention ..."

By the middle of the 20th century, it was hard to find a Bouguereau painting being sold at auction or any reference to him at art schools, except as an example of what not to do.

William Bouguereau, "Self-Portrait," 1879, The Montreal Museum of Fine Arts.

But the show at the Frick, along with recent auctions at which Bouguereau paintings have sold for more than $2 million, may be an indication that his stature is on the rebound.

If that's true, it could have something to do with several years of proselytizing by a millionaire New Jersey businessman and art collector named Fred Ross.

Ross sponsors the Web site www.artrenewal.org, which features nearly 63,000 images, most by academic and classical painters. Bouguereau holds a special place of pride on the site, with 226 of his paintings posted there.

But the Web site is more than a repository of images. It is also a platform that Ross and his supporters use to extol the virtues of academic artists and castigate nearly everything associated with modern art.

"For over 90 years," one of Ross' essays says, "there has been a concerted and relentless effort to disparage, denigrate and obliterate the reputations, names and brilliance of the academic artistic masters of the late 19th century. ... It is incredible how close Modernist theory, backed by an enormous network of powerful and influential art dealers, came to acquiring complete control over thousands of museums, university art departments and journalistic art criticism."

In a 2002 speech to the New York Society of Portrait Artists, Ross recalled his 1977 encounter with Bouguereau's 8 1/2-foot-high painting, "Nymphs and Satyrs," at the Clark Art Institute in Williamstown, Mass.

"Frozen in place, gawking with my mouth agape, cold chills careening up and down my spine, I was virtually gripped as if by a spell that had been cast," Ross said. "Years of undergraduate courses and another 60 credits post-graduate in art, and I had never heard [Bouguereau's] name. Who was he? Was he important? Anyone who could have done this must surely be deserving of the highest accolades in the art world."

Strengths and weaknesses

Not everyone subscribes to Ross' views. Even artists who aren't fans of modernism object to his canonization of Bouguereau.

Bouguereau's "Madonna and Child with St. John the Baptist"

Mark Vallen, a California realist painter, wrote on his Web site, www.art-for-a-change.com, that Ross and his supporters "are not incorrect when noting the follies of modern art, but their total rejection of it is beyond the pale and thoroughly reactionary."

"Bouguereau's strength," Vallen wrote in an e-mail, "was his dedication to the craft of painting, and his technical mastery of oil painting can't be denied. If today's artists knew but a fraction of the painting skills possessed and employed by Bouguereau, they would be better off.

"Nevertheless, Bouguereau was also imprisoned by his extremely conservative vision of what painting could be -- and that was his greatest weakness."

The Frick show doesn't try to fuel the flames of this debate. Instead, it puts Bouguereau in the context of his time and place and shows how his emphasis on precise draftsmanship and painting the human form influenced many American painters in the 20th century, including several who developed sharply different styles.

Bouguereau was especially known for his ability to paint hands and feet, considered the most difficult parts of the body to portray.

That can be seen clearly in "Young Girl," one of his works at the Frick that is a premier example of his "French peasant" style.

The girl stands with her arms crossed, and only a close view reveals that her right hand is holding a clutch of knitting needles (to demonstrate her domestic skill) and a crumpled note (perhaps from a lover). Her bare feet are delicate and hardly look as they they've ever trod outdoors.

The woman's pensive, demure expression symbolizes another reason why Bouguereau's peasant girl paintings were so popular with wealthy American collectors in the Victorian era, says Claudia Giannini, an artist and museum writer based in Morgantown, W.Va.

Bouguereau "was selling primarily to rich, white male industrialists," Giannini said. And while "there's kind of an underlying eroticism" in his peasant girl paintings, "these women are no trouble."

The rural scenes represented a "prettified real world," Zafran added. "He's giving his buyers something they can recognize and enjoy but making them just pretty enough you could hang them in your home."

Bouguereau also painted many nudes, which were often criticized for being salacious. One of the most famous examples was the "Nymphs and Satyr" canvas that mesmerized Ross 30 years ago.

It was acquired in 1882 by one of the owners of the Hoffman House, a popular New York City bar, where it was placed so it was reflected in the bar's mirror.

For the next 19 years, it hung in the saloon and was viewed by an all-male clientele that included Buffalo Bill Cody, Ulysses Grant, Grover Cleveland and P.T. Barnum, Zafran wrote.

Female perspective

Giannini said she is not a fan of Bouguereau -- "in my personal opinion, art is about showing us something new, and Bouguereau didn't" -- but she admired him for championing women artists at a time when it was very difficult for them to become noticed.

His most famous female student was Elizabeth Gardner, a New Hampshire woman who painted pictures so much like Bouguereau's that it was often hard to tell them apart, and who eventually became his second wife.

Pearo, who did his doctoral dissertation on Gardner, said she is a fascinating story in her own right, and she is "the first documented case of a self-supporting woman artist."

Nevertheless, Pearo said, Gardner had to put up with insinuations that her success wasn't due to her talent and with unproven allegations that Bouguereau even finished her paintings for her.

"She just accepted it," he said. "She would say, 'I'd rather be the best imitator of Bouguereau than nobody.' "

A matter of perspective

Bouguereau's success at marketing his work and his prolific output made him wealthy, but he did not live an indulgent life, Zafran said.

"He sort of played off the idea of the working Renaissance artists," he said. "This was a job that you worked hard at."

That may even be one reason his stature declined in the 20th century, Zafran said.

"Artists who lead a more crazy life and party and drink may be more interesting to the public," he said, "whereas these academic painters were much more self-contained."

But Ross, the New Jersey collector, contends that Bouguereau continues to appeal to many people today.

Even though his Web site is packed with images by such leading Renaissance artists as Michelangelo and Raphael, Bouguereau's paintings are viewed twice as often as those of any other artist on the site, he said.

That by itself doesn't prove Bouguereau is universally popular, though, and Zafran says it may be only natural that people hold very different views of him.

When Bouguereau died in 1905, he was nearly 80 years old. Living in Paris at the same time were Claude Monet, then the 65-year-old dean of the Impressionists, and 24-year-old Pablo Picasso, who was just setting out on a path-breaking career.

"These three generations were all competing with each other," Zafran said. "In some ways, it seems we've never made peace with that idea."

First Published: August 20, 2007, 8:00 p.m.