The Homestead Works boomed in the late 1950s, with plate and slab mills in the foreground and the smoke-belching Open Hearth No. 5 on the other side of the Homestead Grays Bridge.

Pittsburgh Post-Gazette

Twenty years ago this month, a fire-breathing monster died with barely a whimper.

The Homestead Works of U.S. Steel, which at one time produced nearly a third of all the steel used in the United States, shut its doors July 25, 1986, when a lonely band of two dozen men drove out the Amity Street gate for the last time.

Two years later, U.S. Steel sold the site to the Park Corp., which tore down most of the buildings, sold tons of metal as scrap and transformed what had been America's busiest steel complex into a desolate moonscape.

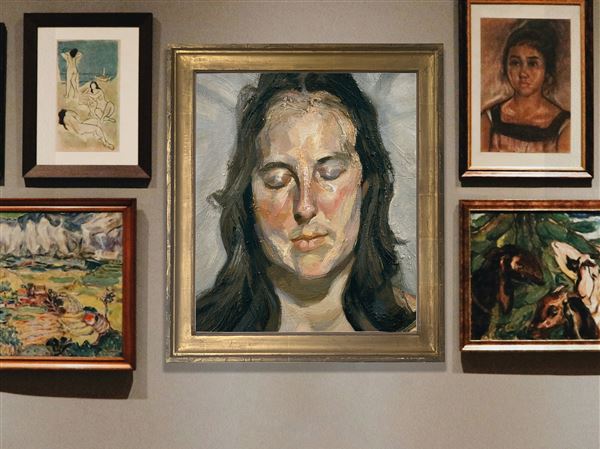

Martha Rial, Post-Gazette photos

Mr. Andrejchak describes his abrupt layoff in 1984

Mr. Andrejchak describes his abrupt layoff in 1984

Mr. Czakoczi describes working in the heat.

Mr. Czakoczi describes working in the heat.

Mayor Esper describes how she got started at the steel mill.

Mayor Esper describes how she got started at the steel mill.

Mr. Monk, a former bricklayer at the mill, describes what it was like to replace bricks in red hot furnaces.

Mr. Monk, a former bricklayer at the mill, describes what it was like to replace bricks in red hot furnaces.

Mr. Stout describes what it was like when U.S. Steel closed the mill.

Mr. Stout describes what it was like when U.S. Steel closed the mill. After nearly a decade of lying fallow, much of the 430-acre site put on new clothing and began life as The Waterfront, a shopping center with restaurants, a movie theater, apartments, offices and an array of big-box, department and small stores.

In the two decades since the Homestead Works closed, a generation of Pittsburghers has grown up knowing hardly anything about the former steel mill, let alone the steel industry itself.

When Christine Rounds, 13, and sisters Kelsey Scanlon, 13, and Samantha Scanlon, 11, were asked outside Abercrombie & Fitch what used to be on the land before the shopping center, Samantha ventured: "Steel mills?"

And what was the mill called? Giggles all around.

Had they noticed any parts of the old steel mill still standing?

"Oh, yeah," Samantha said excitedly, gesturing over her shoulder. "Those big round poles."

The poles are the 12 towering smokestacks that used to vent heat from red-hot steel ingots waiting to be reshaped in the 45-inch slab mill. They now stand like lonely sentinels at the edge of the Loews Theater parking lot.

The ingots came primarily from the vast Open Hearth No. 5 building on the other side of the Homestead Grays Bridge. Its 11 furnaces, operating at a white-hot 3,000 degrees, stretched all the way from Dave & Buster's to the Eat'n Park restaurant near the Monongahela River.

And that was just part of the picture. At its peak, there were 450 buildings crammed onto the site, operating around the clock, seven days a week.

In its 105-year history, the Homestead Works produced more than 200 million tons of steel: Rails and railroad cars, armor plate that covered battleships and tanks from the Spanish-American War through the Korean War, and beams and girders that went into the Empire State Building, the Gateway Arch in St. Louis, the U.S. Steel Building in Pittsburgh and the Sears Tower in Chicago.

In 1892, just a few years after Andrew Carnegie bought the mill, it was the site of the infamous Battle of Homestead, in which locked-out steelworkers squared off against Pinkerton guards who had come up the river on barges to reopen the plant.

After a day of sporadic gunfire, 10 people were dead and the Pinkertons had surrendered. But eventually, Carnegie and his top lieutenant, Henry Clay Frick, won the war, and unionization among steelworkers was effectively snuffed out in America for the next four decades.

After the U.S. Steel Corp. was formed in 1901, the Homestead Works continued to grow in importance, and in World War II, an entire neighborhood of 8,000 people was razed to expand the mill even further.

Those glory years for Homestead were a far cry from 1986, when 23 men were left to finish up at the No. 2 Structural Mill.

William Serrin, a former New York Times labor writer who detailed the mill's history in his 1992 book, "Homestead: the Glory and Tragedy of an American Steel Town," said that on that final day, crane operator Ed Buzinka looked at him and said: "Well, that was that. It's over. But I'll tell you what. It was a good run while it lasted."

That same attitude, a mixture of pride, resignation and bitterness at the way the company treated the mill workers, prevailed one day last week when six former steelworkers gathered at the Steel Industry Heritage Corp. headquarters in Homestead.

Mike Stout, 57, the youngest of the group and former grievance chairman of Local 1397 of the United Steelworkers, said there were four things people should remember about the Homestead Works.

"One, there was a mill here. Two, it was the most productive mill in the world. Three, it was the most profitable mill in the world. And, four, they should remember the way that U.S. Steel shut it down and the way they treated people who were the most faithful, loyal, hardest-working employees you've ever seen."

When Mr. Stout started at the mill in 1977, U.S. Steel employed 166,000 people overall. By the time he left 10 years later, the work force had declined to 33,000. The Homestead Works itself peaked at 15,000 employees during World War II, and had slumped to half that number by 1984.

As the company closed one part of the Homestead Works after another in the '80s, Mr. Stout said, it would routinely lay off whole groups of workers who were months short of qualifying for their 20-year early-retirement pensions.

Richard Andrejchak, who worked his way from laborer to general foreman during 39 years at the mill, agreed.

"I knew a guy, he used to come in at 5 in the morning to see what [steel] they were going to roll that day. I'd be going home at 5:30, and he'd still be there till maybe 7. He was dedicated.

"That poor guy had one month before a 20-year pension and they wouldn't let him work one more month. The guy cried like a baby. He just begged them to give him one month."

Illustrated map: Homestead Works: Yesterday and today

Illustrated map: Homestead Works: Yesterday and todayBetty Esper, the longtime mayor of Homestead who worked in offices at the plant for 35 years, recalled one particularly brutal layoff day among supervisors in 1984.

"The phone would ring," she said, "and they'd say, 'Send so-and-so over,' and then so-and-so would come out, open his locker and throw everything in the garbage can and walk out.

"I went to my boss in tears and said, 'I can't go through this anymore.' I'm watching these young men come in, 40 years old, 45 years old, losing their jobs. It was heart-wrenching. Where do you go at 45?"

U.S. Steel spokesman John Armstrong acknowledged that the company "made the decisions about which departments to idle or close and when," but said the benefits workers received were "governed by the provisions of the collective bargaining agreement."

For the workers, the layoffs were all the more shocking because the Homestead Works had been booming during the 1970s.

When the final decade at Homestead began, the steelworkers were making 85 percent more in wages and benefits than the average U.S. manufacturing worker, Mr. Serrin wrote.

Even when later contracts wrung $2 billion in concessions out of the United Steelworkers, it was not enough to stem the tide, and, by 1982, the company announced it would close the last of the furnaces in Rankin that had supplied iron to the Homestead Works, and would shutter the massive Open Hearth No. 5.

Mr. Armstrong, the U.S. Steel spokesman, said that as painful as the closings were, they were necessary to the company's survival.

"Homestead was one of the many plants closed in the 1980s and early 1990s because the markets for its product lines were shrinking, there was a glut of foreign steel coming into the U.S. and it was no longer globally competitive," he said.

"Those tough decisions allowed us to invest in the new technology that has made our company viable today and able to better weather the cyclical nature of our business."

The former workers who gathered last week conceded that many of their colleagues took advantage of the incremental shutdown at Homestead by hauling off truckloads of material, everything from computer paper and water fountains to cranes and machinery.

"There was massive looting," Ms. Esper conceded. "But U.S. Steel didn't care. It was just an easy way of cleaning up the mill."

Today, U.S. Steel still maintains a presence at the site in the form of its Research and Technology Center, which is across from the No. 1 Pump House, where the embattled steelworkers faced off against the Pinkertons.

The only other living remnant of the site's past is a steel fabricating plant, which sits near the Rankin Bridge, operated by Italian-owned Marcegaglia Group.

But the shopping center is the heart of the site now, and most of the former steelworkers embrace it, saying half a loaf is better than none.

They want people to know what went before it, though.

Their work was dirty and dangerous, they said, but in the days before mills became highly automated, it meant they labored as part of crews of people who had to watch out for each other and rely on each other.

George Monk, who worked for 42 years in the mill as a bricklayer and estimator, summed it up this way: "Nobody misses the steel mill, but they miss the people they worked with."

Along with fond memories of camaraderie, though, there's a persistent sense of abandonment.

Mr. Andrejchak still remembers how he was called into his boss's office one day in 1984, with no warning. and "I was told to pack my bags and get everything out of my desk and hit the road."

He had one son in college, another in high school and two cars in the garage. The only saving grace was that he had just made his last house payment.

To Mike Stout, the shutdown of the Homestead Works will always seem like the end of a bad marriage.

"Imagine if you're a housewife and you're married to some guy and he makes you work in a kitchen that's like 110 degrees every day to cook his meals and scrub his floor, and you do that for 40 years, and then, all of a sudden, you come in one day and the door's locked and there's a sign saying, 'Get out.'

"That's how radical I think it was for the people of Homestead. It was like somebody came and pulled the floor out from underneath them."