When Jeria Quesenberry visits an elementary school to talk about computing, teachers often tell her to focus on the girls. Make the lesson plan about Elsa from the “Frozen” movie or another Disney princess, they suggest to the associate professor in the information systems department at Carnegie Mellon University.

Ms. Quesenberry appreciates the recognition that girls should be encouraged early and often to participate in fields like information systems, computer science, engineering and mathematics.

But this approach to teaching is part of the reason the gender gap still exists, she says.

Rather than “conforming” to the idea that the only way to get girls interested in computing is to put it in the context of Disney princesses, Ms. Quesenberry would prefer to focus on movies in general, letting the kids pick out their favorite movie regardless of genre and gender.

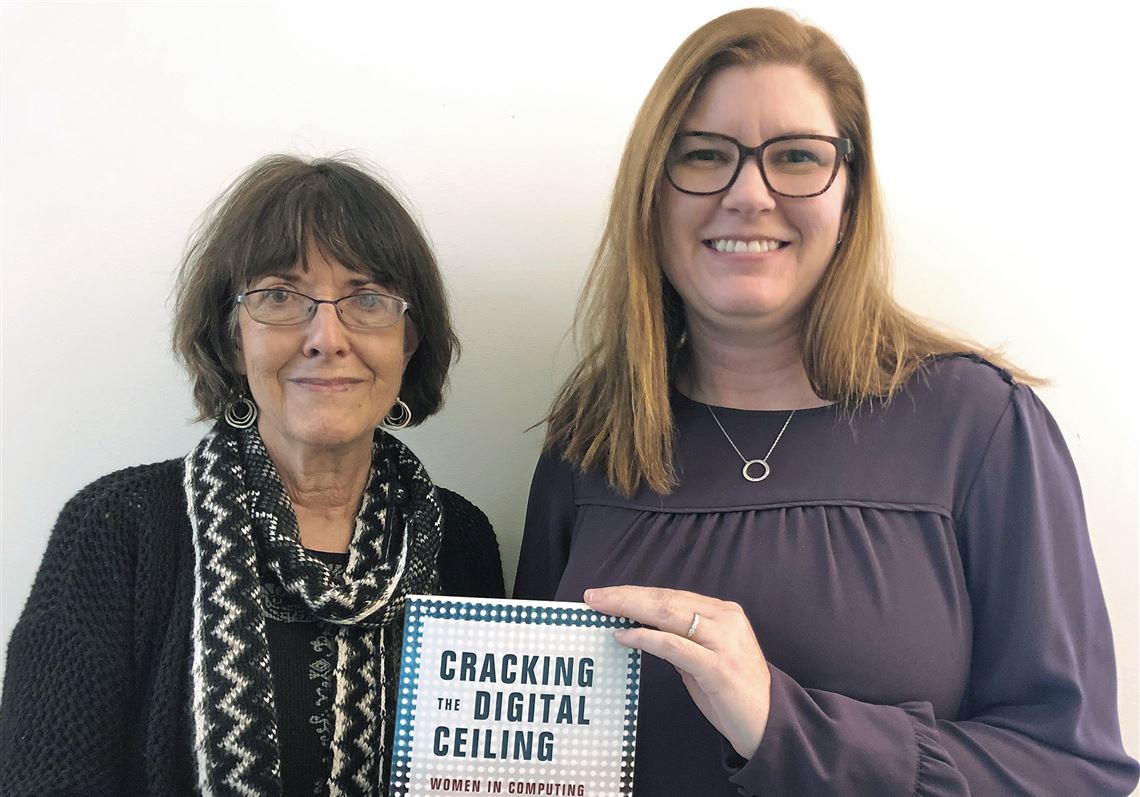

Ms. Quesenberry and her colleague Carol Frieze, who works in CMU’s School of Computer Science, want to challenge the idea that boys and girls learn differently and have different preferences — looking at things as targeted as the lesson plans in elementary school to issues as systematic as fewer women working in computing fields than men.

The two women began working together more than 10 years ago after realizing their shared interest in how culture plays a role in gender inequality.

At CMU, they have conducted surveys and gathered anecdotal evidence from students in computing departments. They wrote a book in 2015, titled “Kicking Butt in Computing Science: Women in Computing at Carnegie Mellon University,” about how CMU developed a culture where women could thrive in computer science.

Through their research, they determined there was a spectrum for students’ interests in computer science — and gender did not determine who was at which end. Instead, the spectrum was divided by things like motivation, background, reason for getting into the field and preference — people who liked coding and people who tolerated coding, people who liked JavaScript and people who preferred C++.

“We found a spectrum of attitudes that cuts across gender,” Ms. Frieze said. “We started talking about culture many, many years ago. Now everybody talks about culture.”

The global view

In their newest endeavor, a book titled “Cracking the Digital Ceiling,” the two computer scientists took a global approach to the problem. The book, published by Cambridge University Press and set to release in 2020, features a collection of essays from women in computing fields around the world.

The goal is to point out how cultural standards and gender norms impact the gender gap in computing, the authors said.

In the 2017-18 academic year, 78% of the total people awarded bachelor’s degrees in computer science and computer engineering in the United States and Canada were male, according to a survey from the Washington, D.C.-based Computing Research Association. That same year, 69% of master’s degrees awarded in those fields went to men. On the doctoral level, 78% of Ph.D.s awarded were to men.

“The numbers of women and minorities in computer science has been low for many years,” Ms. Frieze said. “Some of the recommendations to address that were saying things like look at gender differences and accommodate those differences. But we know that just doesn’t work.”

As an example, she pointed to the common perception that women don’t like computer science because it is too theoretical. But Ms. Frieze and Ms. Quesenberry found in their research that computer science was too theoretical for everyone. Both boys and girls learned the concepts better when they were rooted in real-world applications.

Their most recent book includes 18 essays from women around the world — from Israel to Sweden to Malaysia to Russia.

Many of the authors had already studied and written about gender and computing, and Ms. Frieze and Ms. Quesenberry had used the work through their own research. With this book, they were hoping to put all those thoughts into one place, creating a picture of how cultural differences have created different types of gender inequality.

The theme that emerged, based on survey data and anecdotal experiences in the essays, is that Western countries are doing the worst.

The Western mindset that boys and girls think differently — or the “blue brain, pink brain” concept as Ms. Quesenberry and Ms. Frieze like to call it — has created a culture that assumes men are innately better at computing than women.

This idea seeps into how computer scientists are portrayed in pop culture, how parents talk to their children about career opportunities and how teachers help their students learn.

In many other countries, computing jobs never got the reputation as being better suited for males, so girls see them as profitable and safe career options.

For example, in India, computing jobs are seen as a safer alternative to working outdoors, where women are more vulnerable to assault and often don’t have access to amenities like a women’s bathroom, Roli Varma, from the University of New Mexico, wrote in one of the essays.

In Malaysia, researchers say computer science and information technology has never been viewed as a masculine field. A 2018 study found female and male students interested in computer science spent the same amount of time hacking computer systems, writing programs outside of their coursework and surfing the internet. The only difference was that men spent more time playing computer games, according to an essay from Mazliza Othman and Rodziah Latih from universities in Malaysia.

Signs of change coming

Though the numbers don’t paint a promising picture, Ms. Quesenberry and Ms. Frieze said they have seen some improvements and they are optimistic things will continue to change.

One example, they said, is that companies and universities no longer question the monetary value of having diverse employees and students. The more opinions, backgrounds and experiences people can bring to creating a product, the easier it will be to market said product to a larger pool of people.

Still, the ongoing debate has flared up even at their CMU base.

The class of 2021, which began in the fall of 2017, was the first in the university’s history to have more women enrolled than men, with 51% of the class filled by females. Last August, two professors from the School of Computer Science resigned and accused the university of “professional harassment” and “sexist management.” In response to Lenore and Manuel Blum’s resignations, CMU set up a new task force to oversee campus culture.

Ms. Frieze, who worked closely with Ms. Blum, said the resignations upset everybody and prompted more serious attention to the problems.

The two authors don’t have any concrete plans to write another book, but they did say their latest volume didn’t include all the countries they would have liked to highlight.

In the meantime, they are celebrating the small victories — like more inclusive lesson plans for elementary school students and the creation of a knock-off Barbie doll who works as a computer scientist.

Lauren Rosenblatt: lrosenblatt@post-gazette.com, 412-263-1565.

First Published: November 19, 2019, 12:55 p.m.