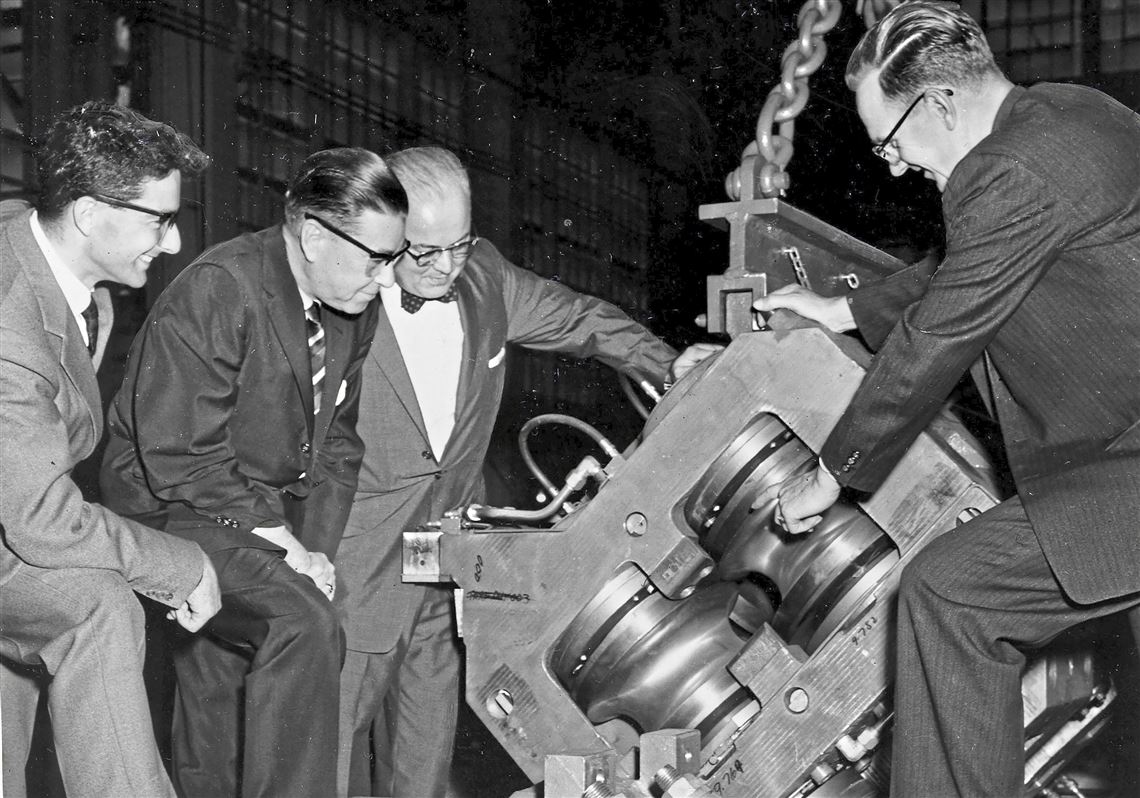

Some 50-plus years ago — when a horde of Pittsburgh-area steel mills still belched an acrid smell of success — the city was a top Fortune 500 headquarters town.

The region was home to roughly two dozen companies on the annual list, with only New York and Chicago claiming more Fortune 500 firms.

It was something Pittsburghers loved to crow about.

Today — following the disappearance or breakup of many of the region’s old-time industrial giants such as Gulf Oil, Westinghouse, National Steel and Jones & Laughlin Steel — Pittsburgh is no longer among the nation’s elite headquarters cities.

In the most recent rankings — which identifies 500 of the country’s biggest companies based on 2017 revenues — seven Pittsburgh-based firms made the list, lead by Kraft Heinz, PNC Financial Services Group and PPG Industries.

New York and Chicago, meanwhile, remained on top with roughly 100 Fortune 500 companies between them.

Anyone feeling teary-eyed about Pittsburgh’s loss of stature, however, shouldn’t.

Experts say all the fuss about having a multitude of corporate headquarters is overblown.

“I am unaware of any economic research that suggests the mere location of corporate headquarters promotes long-term growth,” said Christopher Briem, a researcher at the University of Pittsburgh’s Center for Social and Urban Research.

In Pittsburgh’s case, the past concentration of corporate headquarters “did little to alleviate the loss of competitiveness and jobs in the region’s industrial core,” he said.

Today, almost all of the region’s job growth comes from companies that have not located their headquarters here, including Google, Uber, Amazon, Facebook and Apple.

“Those are the companies creating jobs,” Mr. Briem said. “There’s not necessarily a large multiplier effect from just a corporate headquarters.”

Even though Pittsburgh is no longer at the top of the Fortune 500 rankings, the region has more to be proud of than when it was a manufacturing mecca — and a champion of foul waters and polluted air, experts say.

“I would rather be one of the most livable cities, which we are consistently ranked, than the No. 3 Fortune 500 city,” said Dave Mawhinney, executive director of the Swartz Center for Entrepreneurship at Carnegie Mellon University.

Following the collapse of the steel industry in the 1970s and ‘80s, Pittsburgh reinvented its economic base to include education, medicine and technology.

“We found what we were good at and built on that,” Mr. Mawhinney said.

Having a more diversified economy means the region is better able to survive a downturn and cope with changes in industry than it was at the height of its Fortune 500 fame.

“The secondary effects have been amazing,” he said. “We went from Primanti’s being a gourmet night out to being a Zagat five-star restaurant city.”

Decades ago when Pittsburgh was in its industrial prime, the Fortune 500 only included companies from the manufacturing, mining and energy sectors. That makeup gave the grittiest cities like Pittsburgh the best shot at having lots of companies on the list.

In 1994, service companies were added for the first time, allowing large corporations such as Walmart and AT&T to make the rankings.

Today, one out of three Fortune 500 firms are located in just six major metropolitan regions: New York (65 companies), Chicago (33), Dallas (22), Houston (21), Minneapolis-St. Paul (18) and San Francisco (18), according to an analysis by the financial news site 24/7 Wall St.

For anyone still feeling glum about Pittsburgh losing its long-ago standing as a top headquarters town, there’s a glimmer of good news.

Wilmerding-based (and soon to be Pittsburgh-based) Wabtec earlier this year completed its merger with GE Transportation in Chicago.

The marriage gives the company annual revenues of about $8.4 billion, which should land it a spot on next year’s Fortune 500 list and boost Pittsburgh’s headquarters count to eight.

Patricia Sabatini: PSabatini@post-gazette.com; 412-263-3066.

First Published: May 6, 2019, 10:30 a.m.