As a boy, Frank Lloyd Wright developed a love for nature and a rock-solid work ethic while doing back-breaking chores on a Wisconsin farm.

The best known American architect of the 20th century, Wright designed more than 1,000 structures, half of which were built. About 400 Wright buildings still stand, and 74 are open for public tours.

The Frank Lloyd Wright Building Conservancy has issued the fourth edition of “Wright Sites: A Guide to Frank Lloyd Wright Public Places” (Princeton Architectural Press, $22.95). The third edition appeared in 2001, and during the past 16 years, more Wright buildings have been saved and opened to the public.

Also, this year is the 150th anniversary of the architect’s birth in 1867. In the U.S., 22 states have structures designed by Wright. Western Pennsylvania has Fallingwater, the house balanced atop a waterfall, and Kentuck Knob, both in Fayette County. If you would like to stay overnight in a Usonian home, a style Wright created for homeowners of modest means, Polymath Park in Acme, Westmoreland County, has the Duncan House. Two other homes on the property are the work of Peter Berndtson, a Wright apprentice.

Wright-designed buildings that are open for tours include a Minnesota gas station, a retail building on Rodeo Drive in Beverly Hills, Calif., the Solomon Guggenheim Museum in New York City, places of worship and private homes.

Although some operate as house museums, many remain private residences.

“They just have owners who run small tour operations,” said Joel Hoglund, editor of the new guidebook.

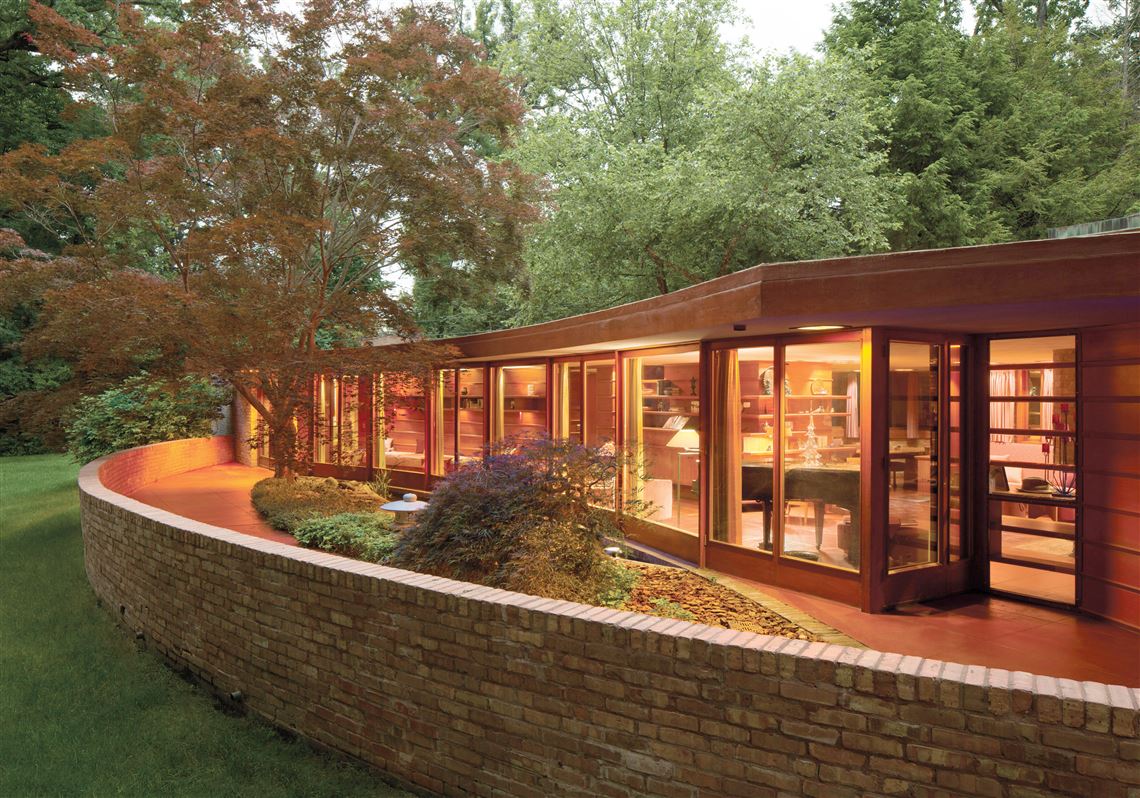

Among the most interesting homes in the book is the Laurent House in Rockford, Ill., the only private residence Wright created for a client in a wheelchair. Kenneth Laurent, a Navy veteran who served during World War II, wrote to the architect in 1948 and asked him to design a home for him. Finished in 1952, the single-story residence has and wide doorways, hallways and bathrooms and no thresholds. The home predates the Americans With Disabilities Act by nearly four decades.

The Bachman-Wilson House was built in Millstone, N.J., in 1954, but it’s not there anymore. After it was restored in 1988 by Lawrence and Sharon Tarantino, an architecture and design team, it was repeatedly flooded by the Millstone River. The Tarantinos and the Chicago-based Frank Lloyd Wright Building Conservancy agreed the home should be moved. In 2014, the Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art bought the home and moved it to Bentonville in northwest Arkansas. The two-story house, which has Philippine mahogany elements, now overlooks a woodlands and Crystal Spring.

The book includes three projects in Japan, a country whose culture and art fascinated Wright. The most famous is the Imperial Hotel in Tokyo, built from 1913-22. Thanks to the architect’s innovative design and use of local brick and steel-reinforced concrete, the hotel suffered only minor damage when the Great Kanto Earthquake hit in 1923. The hotel was razed in 1968 and its entrance hall, lobby and reflecting pool reconstructed in the 1980s. Also featured in the book are the Yodoko guest house (1918) in Hyogo and Myonichikan school (1921) in Tokyo.

The conservancy’s mission, Mr. Hoglund said, is to care for buildings Wright designed.

“The best way to do that is through private ownership, with people still using the buildings for what they were originally designed for. If they can’t be used as a private home, the value of a building as a public site almost pays greater returns. All these new people can be exposed to Wright’s work,” he said.

Like a great work of literature or music, Wright’s architecture includes elements of surprise.

“You can find something new. There is a level of artistry to it that you don’t often see in the kind of architecture that most people are exposed to on a day-to-day basis,” Mr. Hoglund said.

Marylynne Pitz: mpitz@post-gazette.com, 412-263-1648 or on Twitter: @mpitzpg.

First Published: April 30, 2017, 4:00 a.m.