The Penn State men’s basketball program has a credibility problem in the wake of coach Patrick Chambers’ resignation last month at the conclusion of an internal investigation into his conduct.

Details of that report have not been divulged publicly, or even within the program, as players last week fumed during their 2020-21 media day that they have not been given satisfactory answers about why the coach they supported, to a man, departed less than a month before this season was set to begin. And after the program’s best campaign in almost 20 years.

Vice president for intercollegiate athletics Sandy Barbour has said her department will not be disclosing details of the investigation, echoing institutional secrecy that a decade ago led her immediate permanent predecessor to a prison term for his role in the Jerry Sandusky scandal. Until that changes, administration alone will not be able to rebuild trust inside or outside the Bryce Jordan Center.

That task will primarily fall to the person chosen to replace Chambers. And at least one whose name would command instant credibility within the school’s close-knit basketball community wants the gig.

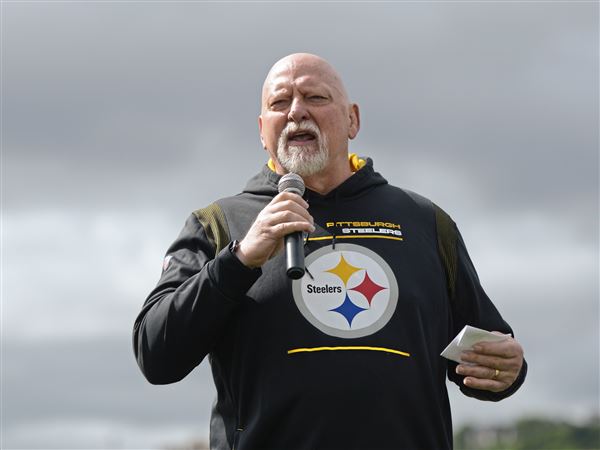

Joe Crispin was the face of the Nittany Lions’ 2000-01 squad that advanced to the NCAA tournament’s Sweet 16. It was the program’s deepest run since it reached the Final Four in 1954, and no Penn State team has come close to matching it since.

Crispin led that group — which also featured names including Gyasi Cline-Heard and Titus Ivory — with an average of 19.5 points per game and was the key cog to massive upsets of defending national champion Michigan State in the Big Ten tournament as well as second-seeded North Carolina in the NCAA tournament.

Even a football-crazy school that’s traditionally treated its basketball program as an afterthought can remember success like that rather vividly. And while he is adamant about showing deference to players and interim coach Jim Ferry as they navigate this difficult situation, when the time is right, he’s also clear about wanting to leave his mark on the program again, this time as its coach.

“I am all in on helping Penn State basketball become the success we all want it to be and believe it can be,” he told the Post-Gazette on Tuesday. “It is certainly as personal as it gets for me in that I view Penn State as my home for life. I am sure that sentiment is shared by all of us as alumni and members of the community. But I am hoping for a bright future no matter what for Penn State basketball.”

His resume is not conventional for a job at the Big Ten level. He’s spent most of his professional life as a player in the NBA, ABA and overseas.

He’s pursued coaching opportunities since retiring in 2012 and has been at NCAA Division III Rowan University since 2014, first as an assistant, then as the head coach beginning in 2016. In that time, he’s guided the Profs to their first conference title in 20 years and established his program as a more prominent part of life on a bustling campus of almost 20,000 students.

Still, taking the reins at Penn State would be a big jump for a 41-year-old in a profession that forces almost everyone to pay dues and climb ranks one by one. Crispin understands but feels his philosophy is fresh and at the leading edge of the evolution he expects across the sport in the years ahead.

“Most people who know me as a player, especially in this area, knew that I was going to be committed to scoring and playing fast, just a fun style of ball,” he said. “The way I put it is I want to give my players the style of play I always wanted. And figure out a way to win with it. One of the things I always thought as a player is that when you establish a little bit more of a free-flowing game, more players are able to play that way than coaches often think. That means various backgrounds, athleticism. A little less athletic, more skilled. A little less skilled, more athletic. A variety of players just thrive in that kind of game.

“I think at every level of play, there’s such a balance in basketball. But at the higher levels of play where there’s more pressure and more exposure to criticism, it’s very easy to want to exercise more control over the game from a coaching standpoint. And like any coach, you want to know what’s coming, but I just love a game of basketball that is spontaneous, that is a little bit unpredictable and that players own. I really just believe in a player-owned game.

“I think that’s where the game is going in the NBA, and there is going to be a trickle-down effect, but there’s a window right now to enjoy that and to capitalize on it.”

So, yeah, Penn State would have to make the hire with an eye toward innovation rather than a proven track record at the highest levels. Think Kliff Kingsbury turning the Arizona Cardinals into a playoff contender soon after getting fired from his previous job at the college level.

That doesn’t mean abandoning the foundation that Chambers built. Past coaching transitions at Penn State have been rough, with mass exoduses following the departures of Jerry Dunn a couple of years after Crispin graduated and Ed DeChellis in 2011.

Crispin is as aware of that history as anyone and feels it’s important to avoid repeating it where possible.

“Speaking as an alumnus, just a consistency of identity is super, super important as a program,” he said.

“It’s a super important thing in recruiting, it’s super important in community interest and really being successful in the Big Ten. When you look at the programs who are the most successful, you see teams and programs who really know who they are, and that’s often what wins over the long term.”

It’s for that reason that he’d prioritize retaining as much of the existing roster as he can, because he believes it’s talented and represents the real gains Chambers was able to make in recruiting.

He believes he can build on those gains, too, as he’s intimately familiar with the Philadelphia-area scene where the Lions thrived on the trail under Chambers, attracting future stars including Lamar Stevens, Mike Watkins and Tony Carr. Rowan is located just 30 minutes outside the city.

Add his extensive international experience to the mix and he believes there are many areas where he can continue to find talent and field a roster full of Big Ten-caliber athletes, which hasn’t always been easy at Penn State.

Long-time fans will point to administration as the primary reason. As recently as the team’s 2011 NCAA tournament run, the team was famously forced out of its Jordan Center practice digs and into the run-down Intramural Building, which at the time had crooked rims and stanchions for volleyball posts in the floor. All so the rocker Jon Bon Jovi could use the Jordan Center to practice for a tour.

Crispin has similar stories from his playing days. He’s hopeful indignities like that are in the past but recognizes there will be limitations on the program he’d be leading, too. He’s OK with that.

“At Rowan, my players and I and one of my assistants literally rebuilt our locker room one year,” Crispin said. “And we used it as kind of a motivation and an impetus to say, ‘We’re going to beat the teams that have nicer things than we do.’

“Of course you want to make some things better, and I do think they are better. Pat did a good job with that, the administration now has done a good job of that. But even if you don’t have everything everyone else has, you can use that to your advantage.”

While that might be true, commitment — financial or otherwise — isn’t the only administrative issue facing the program at this point. The lack of transparency surrounding Chambers’ departure leaves far more questions than answers about how this program moves forward.

Can any candidate trust that Barbour and Co. will treat them fairly? Chambers didn’t get to face any accusations of wrongdoing publicly, other than those raised by Rasir Bolton, a Black former player who told the Undefeated earlier this year that Chambers referenced removing a noose from around his neck.

Can recruits commit to Penn State without worrying that the coach they formed a relationship with will be swept aside without explanation?

Can current players trust anything that athletic administration tells them? Senior Jamari Wheeler described being told that “everything was good” by staffers only hours before Chambers resigned.

It is a mess that X’s and O’s can’t clean up and that has likely only escaped wider scrutiny because of the 0-5 football team’s struggles and the fan base’s historically apathetic view of hoops.

Crispin was understandably reluctant to weigh in on that topic without knowing the facts, which only Penn State can provide, other than to say that he plans to be as transparent as anyone in the rough-and-tumble world of college athletics can be.

“On a personal level, absolutely,” he said. “I’m very clear about who I am and what I stand for and what my program wants to stand for. And you want to be a wide-open book in that regard, and encourage access and interest.

“From an administrative standpoint, it’s tough to say. I don’t know all the intricacies involved. And the reality is, everyone wants more answers, but at the same time, just living in the world that we live in, particularly at a university level, there are some things you can’t speak to even if you want to.”

That may be true. For now, though, the players’ comments last week lay bare how little benefit of the doubt administration is being afforded. And it’s not as if this is the only massive disappointment they’ve dealt with in the past year either.

The pandemic cost them their first NCAA tournament appearance since 2011, as March Madness was canceled amid an early outbreak. Morale is low.

Crispin gets it, perhaps more than an outsider who’s unfamiliar with this program’s ups and downs could. But he hopes he can be part of the healing process.

“The Number 1 thing is empathy and just the understanding that for them, that does stink,” he said. “It doesn’t matter what factors are involved and how you feel about it. For them, it certainly stinks.

“Number 2, you want to encourage them to learn from it, and then in turn, you want to do what’s best for kids. There’s no getting around it.”

Adam Bittner: abittner@post-gazette.com and Twitter @fugimaster24.

First Published: November 30, 2020, 1:00 p.m.