Al Oliver still has his doubts.

Fifty years ago Friday, Dock Ellis no-hit the San Diego Padres, the fifth such game in Pirates history lasting a mere 2 hours, 13 minutes, as Ellis walked eight, hit one and struck out six. Willie Stargell belted a pair of solo home runs in the 2-0 victory, and Bill Mazeroski kept the no-hitter intact with a clutch grab in the bottom of the seventh.

While all of those details are certainly important, they pale in comparison to what Oliver still questions to this day: Did Ellis really throw a no-hitter while on lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD)?

“I know this,” Oliver recalled by phone last week, “if you can pitch a no-hitter on LSD, you should be in Cooperstown. I don’t think anybody could pitch a no-hitter on LSD. I don’t think a player could play on LSD.”

Ellis is not a member of the National Baseball Hall of Fame, although he did go 138-119 with a 3.46 ERA over his 12-year career. In 1971, the season after his no-hitter, Ellis was an All-Star, going 19-9 with a 3.06 ERA and finishing fourth in the National League Cy Young Award voting.

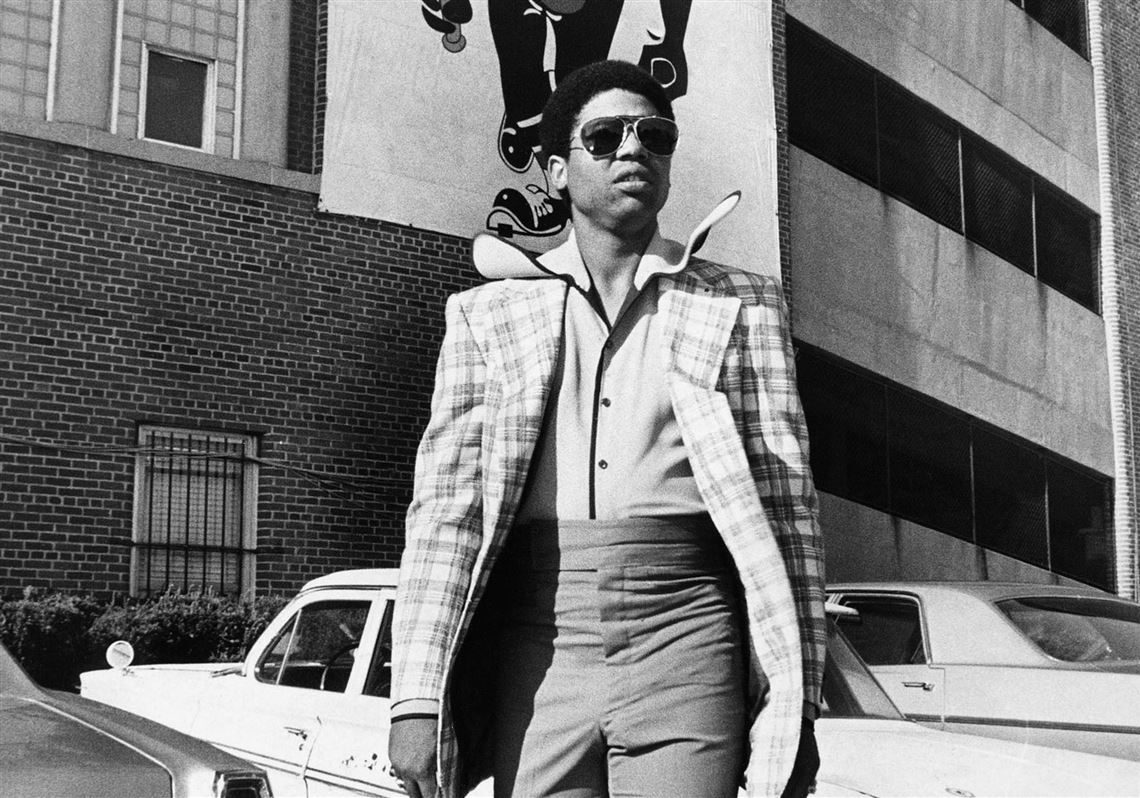

But instead of individual accomplishments, Ellis’ career is best defined in different ways. By the no-hitter on acid, sure, but also Ellis’ eccentricity, for saying and doing whatever he wanted and generally detesting authority. Or for something that would likely make Ellis an important and popular figure in pro sports today: voicing his opinions on race, discrimination and social injustice.

Ellis, who died from liver disease in 2008 at age 63, claimed he never pitched a game in the major leagues when he wasn’t high. After he retired from baseball, Ellis sobered up and became a substance-abuse counselor.

Starting at first base the night of Ellis’ no-hitter, Oliver thinks back to that game often. June 12, 1970. Start of a true doubleheader. Oliver remembers Ellis’ wobbly control, along with being shocked to learn around the sixth or seventh inning that the Padres had zero hits.

“Looking at Dock that night, he looked like Dock to me,” Oliver said. “The only exception was that Dock always had good control. There were times when he got behind on hitters, but LSD was the last thing on my mind.

“Then again, if there was anybody who could have done it, it would have been Dock. I’ve seen Dock do some pretty strange and funny things.”

‘He could pitch’

Steve Blass didn’t pitch that night. After starting three days before, Blass’ turn in the rotation wouldn’t come around until the next night, when he tossed his own complete-game gem while allowing two earned runs and striking out 10.

During a casual conversation with a few writers covering the team at the time, Blass joked that he didn’t know whether Ellis dropped acid but, “Just to hedge my bet, I’m going to get some. … And if you write that, I’ll come to your house.’ ”

Further talk that Ellis may have dropped acid didn’t make it out publicly until years later, after Ellis had pitched for four more clubs and retired. Until that point, it was believed Ellis had been drinking vodka, since that was what appeared in the most widely recognized book on his career — “Dock Ellis in the Country of Baseball,” by former United States Poet Laureate Donald Hall.

But in 1984, former Pittsburgh Post-Gazette columnist Bob Smizik, who back then was with The Pittsburgh Press, actually broke the story that Ellis was tripping on acid.

Blass isn’t sure what to believe. Part of him wants to believe it’s a myth, but Blass also wouldn’t be surprised if it was true.

“It’s hard to believe it enhances a physical performance, but I don’t know,” Blass said. “I never took it. I have no frame of reference.”

Bob Robertson, the third baseman in that game before he was replaced by Jose Pagan for the bottom of the seventh inning, also doesn’t know if Ellis “was or wasn’t” high.

“Dock was always the same to me,” Robertson added. “When he was on the mound, he was a tremendous competitor.”

One of the most vivid memories Robertson has of that day involves sitting in the dugout after he was removed from the game, nervous because he so badly wanted Ellis to complete the no-hitter.

Ellis enjoyed a 1-2-3 seventh, aided by Mazeroski snaring pinch-hitter Ramon Webster’s liner. It was one of just three 1-2-3 innings for Ellis in the game. There was a two-out walk to Ollie Brown in the eight before another quick ninth, with Ellis striking out Ed Spiezio looking to end it.

“Dock was outrageous,” Blass said. “But he could pitch.”

The other side

Dave Campbell, the Padres second baseman and leadoff man, never could figure out Ellis. In 19 career plate appearances against the Pirates pitcher, Campbell had just one hit — a single — and struck out six times.

“I never did have any luck against him,” Campbell said. “For some reason, his ball moved so much right at the end. Might have been from that three-quarters delivery or whatever. The ball would be there when you started your swing, then it would end up somewhere else. I don’t think that was LSD. I just think that was some natural talent that he had.”

What Campbell, who later went into broadcasting, remembers most about Ellis’ pitching style was his aggressiveness.

Ellis threw five pitches but controlled his fastball especially well. He could locate it. He could add and subtract velocity. The pitch moved.

Ellis also hid the ball especially well, Campbell said.

“It seemed to jump on you before you could really pick it up,” Campbell said.

The illusion for the Padres on June 12, 1970 was real, Campbell said. In fact, Campbell likened it to Tom Seaver’s 19-strikeout masterpiece only a couple weeks before (April 22, 1970), when the Mets righty fanned the final 10 batters he faced in the afternoon affair.

While Campbell wasn’t ready to blame either performance on conditions, picking up Ellis’ ball was not an easy task as the sun set in the San Diego sky.

“I don’t think any of us had any idea anything was amiss,” Campbell said regarding Ellis’ potential drug usage. “We just knew we were having a lot of trouble hitting him.”

That was rare for this particular Padres team, a group that held the club home run record (172) until 2016. Nate Colbert had 38, Cito Gaston hit 29 and Brown finished with 23; however, nobody could touch Ellis on this day.

The one thing the Padres were able to do, however, was walk, as Ellis — perhaps because of the LSD — occasionally lacked control. The nine free passes plus three stolen bases allowed created an odd mix in the San Diego dugout, Campbell said.

“Somebody may have had to come in after the game and tell us we had been no hit because we had so many runners on base,” Campbell said. “It never dawned on us.”

‘Dock was Dock’

The LSD story isn’t the only one Ellis’ teammates have to tell about him. Far from it, actually.

Several pointed to the time Ellis put curlers in his hair in 1973. Some chalked it up to a strategic ploy, where Ellis could better wipe sweat from the back of his neck, while others thought Ellis was simply screwing around.

Blass was annoyed because it was a day game at Wrigley Field, and it caused plenty of unnecessary fuss when everyone was hungover.

Robertson remembers standing on the top step of the dugout when manager Danny Murtaugh instructed him to walk out to the bullpen and tell Ellis to remove the curlers from his hair.

“So I go walking out toward Dock,” Robertson explained. “I almost got there. He said, ‘I know why you’re here, big guy.’ I said, ‘You do?’ He said, ‘I’ll bet ya Murtaugh said something about my curlers.’ I said, ‘Dock, look. The only reason I’m coming out here is because Murtaugh told me to come out here and tell you about your curlers.’ He said, ‘I understand.’ … He did take the curlers out of his hair.”

Oliver likes to tell the story about the time Ellis got sprayed with mace by a Cincinnati security guard in May 1972. Ellis had forgotten his ID card, which gave players access to the visitors’ clubhouse at Riverfront Stadium, and was turned away.

“Dock threw a few four-letter words at the security guard, and the security guard pulled out his mace because Dock was really putting it on him,” Oliver said.

“I’ll never forget seeing Dock come in the clubhouse with his eyes all red.”

Oliver also won’t soon forget what happened on May 1, 1974, when Ellis decided he would hit every Reds batter who stepped to the plate. Ellis plunked Pete Rose, Joe Morgan and Dan Driessen; tried but failed on Tony Perez; and threw two balls at Johnny Bench before Murtaugh pulled Ellis.

“Murtaugh comes out to the mound and says to Dock, ‘Well, it looks like you don’t have your good control tonight.’ ” Oliver said. “I had to turn my head because I didn’t want to start laughing. That was Murtaugh’s humor.”

Other favorites include the time Muhammad Ali stopped by the Pirates clubhouse. After some fake sparring between the two trash-talkers, Ali tapped Ellis once or twice in the chest. Ellis went down like a ton of bricks.

“It was one of the funniest things you could ever want to see,” Oliver said. “I wish that was on film.”

Blass told a story about Ellis’ almost comical cockiness. In Montreal. Starting pitchers scuffling. Murtaugh called a meeting and warned that, if things don’t turn around, someone’s going to the bullpen.

“Dock got up and said, ‘Well, who’s going to the bullpen? You know Blass ain’t going to the bullpen. You know [Bob] Moose ain’t going to the bullpen. And you know the Doctor ain’t going to the bullpen.’ ” Blass said. “Murtaugh cracked up. That was the end of the meeting. It was just hilarious.”

Ellis was also smart and calculating. After starting the 1971 season 15-3 with a 2.11 ERA, Ellis basically dared NL manager Sparky Anderson to start him opposite Oakland’s Vida Blue in the All-Star Game when he said, “they wouldn’t pitch two brothers against each other.”

Later that season, on Sept. 1, the Pirates made MLB history by starting the first all-minority lineup, with Ellis taking the ball in a 10-7 victory over the Phillies.

Teammates respected Ellis' honesty, sense of humor and clubhouse presence. Robertson specifically called him "one of the biggest parts of our winning" and lauded the lengths to which Ellis went to protect those with whom he played.

Oliver, meanwhile, appreciated Ellis' ability to stay true to himself — even if that meant speaking out on controversial topics or doing things his own, unique way.

“Dock was Dock,” Oliver said. “He didn’t put on any airs. He wasn’t phony. I think that’s what everybody liked about him. If he was your friend, you knew you had one.”

Jason Mackey: jmackey@post-gazette.com and Twitter @JMackeyPG.

First Published: June 12, 2020, 11:00 a.m.