In the wake of the Penguins’ lackluster postseason disappointment, after they were swept in the first round by the New York Islanders, general manager Jim Rutherford openly questioned his team’s desire.

Perhaps drinking from the Stanley Cup in back-to-back seasons had extinguished the flame that once burned in their bellies, turning a hungry group into one that was content with their past accomplishments.

Something needed to change. And it did.

Phil Kessel? Gone. Olli Maatta? He’s out, too. In their place, the Penguins added a winger with a wicked shot in Alex Galchenyuk. And in Dominik Kahun, they got a quick, versatile forward who can maneuver in tight spaces.

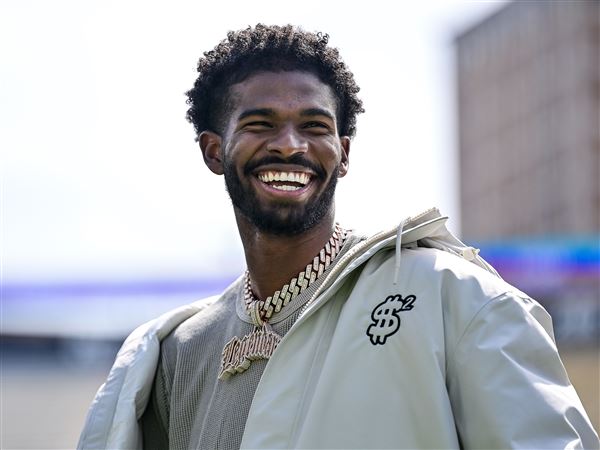

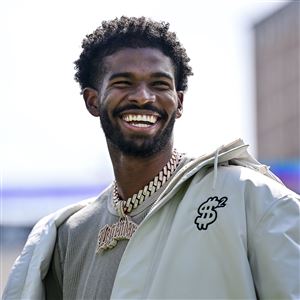

But now, with the 2019-20 season finally here, if you’re looking for the change that could shake up the locker room and provide the missing piece to the Penguins’ puzzle, it just might be 27-year-old forward Brandon Tanev.

Talk to Tanev’s former coaches and teammates, and you’ll hear words like fast, physical, tenacious and relentless on pucks. Look at the stats, and you’ll see a player who tallied the third-most hits in the NHL and blocked the most shots of any forward in his final year with the Winnipeg Jets.

But if you want to know exactly what Tanev brings to the locker room, you have to talk to the man himself.

“Every shift,” Tanev said. “You have to look at it like it’s your last.”

Sounds like a tired cliché, right? Not exactly.

When he was 15 years old, Tanev was deemed too small to play. He was cut and couldn’t find a ice hockey team that wanted him.

So, he gave up the game entirely for four years, thinking that he really had played his final ice hockey shift. If he only knew then how his career would unfold.

Now, with a six-year deal and an opportunity to play next to superstars such as Sidney Crosby and Evgeni Malkin in the Penguins’ top-six, the player once brushed aside without much thought could be the spark that reignites the Penguins’ dormant flame.

■ ■ ■

Tanev’s story starts like so many others in the hockey-obsessed greater Toronto area.

In a family of three boys — Christopher was the oldest, followed by Brandon and then Kyle — they were skating almost as soon as they could walk and playing traveling hockey by elementary school.

At one point, all three were playing AAA hockey on different teams. Mom took one kid to his game. Dad took another. Grandpap took the third.

“It was definitely a bit of a circus getting everyone to their games and practices on time,” Christopher said.

Christopher entered the 10th grade expecting to play another season with the Mississauga Reps, a AAA hockey team in the Greater Toronto Hockey League. His coach had a different idea. He called Christopher into his office after tryouts and laid it on the line. Christopher was hardly 5-feet tall. He was just simply too small to play at the elite level.

In a last-ditch effort to keep his skills sharp, he practiced once a week with the Toronto Marlies, one of the top youth teams in the area. But it didn’t take long for him to get tired of being the random kid at practice who never got a uniform or a seat on the bench at the games.

“That got sort of awkward,” Christopher said. “You just show up to practice on a team once in a while. So that’s when I stopped playing.”

The next year, Brandon faced the same harsh reality.

At about 4-foot-10 and less than 100 pounds, he was even smaller than his brother was at the same age. The other boys on the Toronto Young Nationals were turning into men. There was no place for a kid on the ice anymore.

So at 15 years old, a time when many of the top players really begin to develop and put themselves on the path to the NHL, Brandon hung up his skates.

“That’s one of the things that’s shaped and molded me as a person and a player,” Brandon said. “It’s a lot of adversity to face. At the same time, when life knocks you down, you have to pick yourself back up and continue to work hard and put yourself in position succeed.”

Within two years, the juggling act stopped, the music halted and the circus folded its tent.

■ ■ ■

Throughout high school, Brandon didn’t play competitive ice hockey at all. He moved on, living life like a “normal” teenager.

He got an after-school job selling clubs at Golf Town (much to the chagrin of his future college teammates, who say he still boasts when he has good round on the course). He hung out with buddies. He played baseball.

But deep down, his passion for hockey remained.

“The love of the game is always there,” Brandon said. “You’re never going to lose that.”

The brothers scratched their hockey itch by playing competitive roller hockey tournaments with Team Ontario and Team Canada. It’s a fast and free-flowing 4-on-4 game with no offsides. The rules were perfect for that little guy to race around the open floor, playing free and loose — elements of his game that are still evident today.

Through it all, their father, Mike, was always looking for an avenue to get his boys back on the ice. He had a saying that was drilled into his sons: “If you’re good enough, they’ll find you.”

They found Christopher first.

He shot up about a foot during the summer before his senior year of high school. His dad had an old baseball buddy coaching youth hockey, who agreed to give Christopher a shot.

One team led to another. Then another. Before long, he had earned a scholarship to Rochester Institute of Technology. After a year of college hockey, he signed a deal with the Vancouver Canucks.

Imagine that. The kid who was too small to make the team in 10th grade was now an NHL defenseman — and an inspiration to his younger brother.

“At that time, you see him going through it,” Brandon said. “It puts the light at the end of the tunnel and a little perspective that it is possible. You’ve just got to continue to work and believe in yourself and good things will happen.”

■ ■ ■

The Markham Village Arena is an old-fashioned rink. The wooden beams are still smoke-stained from a bygone era when the cigarette fog was so thick, you almost couldn’t see the players.

The smoke had finally cleared now. It was time for the greater Toronto hockey community to finally see what they had been missing.

The Markham Waxers invited 130 kids to a four-day tryout with the intent of keeping about 15 for camp.

Years earlier, the Waxers thought Christopher was too small and cut him. The team eventually realized its mistake and traded to get Christopher the season before he attended RIT. Even though Brandon was still only about 5-foot-7 and not even 150 pounds at 19 years old, the Waxers weren’t about to make the same mistake with another Tanev.

“It was very, very unusual for someone to be out of hockey at that age for four years and come back,” said Joe Cornacchia, the former general manager and coach of the Markham Waxers. “A lot of people had their doubts about the kid. I had no doubts whatsoever on his ability.”

The thing that stuck out, even then, was Brandon’s explosive speed. He earned a role on the third line, a checking line responsible for shutting down the opponent’s top players.

It was far from glamorous, but he was playing hockey again. And that was all that mattered.

“He never complained about lack of ice time,” Cornacchia said. “He just accepted his role and worked hard and got better and better all the time.”

The Waxers’ coaching staff used to video tape games and watch them back. They had a hard time finding things to correct in Brandon’s game. In his first and only season with the Waxers, Brandon recorded 42 points in 46 games and was named the club’s Rookie of the Year.

“He seldom did anything wrong,” Cornacchia said. “I’m telling you, if I had 20 players on my team with his work ethic, his desire to succeed, we’d never lose a game.”

After one season with the Waxers, Brandon reunited with his older brother in Western Canada.

Christopher had just begun his career with the Canucks. The Surrey Eagles of the British Columbia Hockey League orchestrated a big trade to bring Brandon to the area.

Almost immediately, his coach, Matt Erhart, noticed what everyone notices: that speed. The first exhibition game, Erhart remembers Brandon had at least three or four breakaway attempts.

He quickly carved out a role for himself, again, on one of the checking lines. Erhart laughs now thinking back on it. Tanev was almost too good at checking, to the point that he typecast himself as a third-liner.

“He ended up being the guy we relied upon to shut down the other team’s top players because he could skate with the other team’s top players,” Erhart said.

■ ■ ■

Throughout hockey circles, the BCHL is known as a scoring league. The best players are usually well above 100 points. In his one season, Tanev put up a whopping 33 points. Not exactly eye-popping numbers.

But there was something about him that Nate Leaman, the newly hired Providence coach, couldn’t get enough of.

“I would say he was very much an unknown,” Leaman said. “We were building a program at the time that was ranked 58th out of 60 teams in the country. I loved his speed. I loved his relentlessness. I loved his compete.”

Leaman brought in a big recruiting class that he hoped would turn around the program. Brandon quickly jumped on board.

If you look back at the old Providence rosters, every player has his height and weight listed. Everyone but Tanev. The first two years, Providence simply listed him at 170 pounds. No height. Two years later, he was 180 pounds. Still no height.

Coincidentally, Tanev was assigned Kevin Rooney, who is now with the New Jersey Devils organization, as a roommate. All four years they lived together. Rooney swears he never saw Tanev sleep.

He was always up early, lifting, running, working out. Talking. Moving. Buzzing around.

“He’s just intense,” Rooney said. “Very intense.”

“I kind of looked up to him, even though we’re in the same class and playing together. It made me want to be like that. He inspires teammates by the way he works. That’s why coaches love him.”

The demands of Christopher’s NHL schedule and Brandon’s college hockey season pulled the brothers in opposite directions. They went almost two years without seeing each other.

Finally, Brandon came back from college after his sophomore season. His growth spurt had finally hit and the work in the weight room further magnified things.

“He came back from college, he was like a totally different guy,” Christopher said. “I was like, ‘Holy hell, who is this kid?’ ”

During Brandon’s junior season, opponents were asking the same question.

The Providence hockey team got hot at the right time and made its run through the postseason and into the NCAA Frozen Four. During the decisive national championship against Boston University, Tanev’s line was assigned to shut down the line centered by Jack Eichel, the NCAA’s Hobey Baker Award winner. (Coincidentally, Eichel now plays for the Buffalo Sabres, the Penguins’ opening-night opponent at PPG Paints Arena.)

Late in the game with the score tied, the Friars had an offensive-zone faceoff. BU called a timeout and came back with the Eichel line. The Friars countered with Tanev’s line.

“We were coming off the bench,” Rooney remembers. “[Tanev] said, ‘Win this one on your backhand. I’m going to come behind you and pick it up.’ He told our other linemates, get a pick and I’m going to rip it on the net.”

It worked to perfection.

Rooney won the faceoff. The other linemates created the space. And there was Tanev, bolting in with his signature speed to fire the championship-winning goal.

That goal was one of the proudest moments on Tanev’s hockey career. But in some ways, it was almost out of character.

“I hope Pittsburgh doesn’t think he’s going to come in and be this high-end offensive guy,” Leaman said, affectionately. “That’s not him. What he is, is he’s third-line, north-south, little sh*t disturber, little just compete, bring it every night. You win with guys like him.”

Oh, Pittsburgh knows. And that’s exactly why the Penguins went out and got him.

■ ■ ■

It hasn’t taken long for Tanev to show exactly the qualities Leaman saw in him.

In Tanev’s first preseason game at PPG Paints Arena, Malkin raced down the ice on a 2-on-1. He zipped a cross-ice pass to Galcheyuk, who came within an acrobatic save from scoring.

But as all eyes were fixed on the thrilling offensive play, there was something that was overlooked.

Back on the other end of the ice, Tanev had thrown his body into the opponent, checking him so hard that all that was left was a broken stick and a loose puck for Malkin to pick up. Pure Tanev. He’s not a player who is going to wow you with his stick handling and individual playmaking. But if you know what to look for, you’ll begin to appreciate what makes Tanev special.

“Some guys might have a harder road than others and overcome different challenges,” Penguins coach Mike Sullivan said. “But my experience being around those guys is it usually helps to shape their character. They don’t take anything for granted.”

In other words, they approach every shift like it’s their last.

Mike DeFabo: mdefabo@post-gazette.com or on Twitter @MikeDeFabo.

First Published: October 2, 2019, 2:17 p.m.