For college basketball fans, the name “Jerome” conjures only one image, one person and one moment.

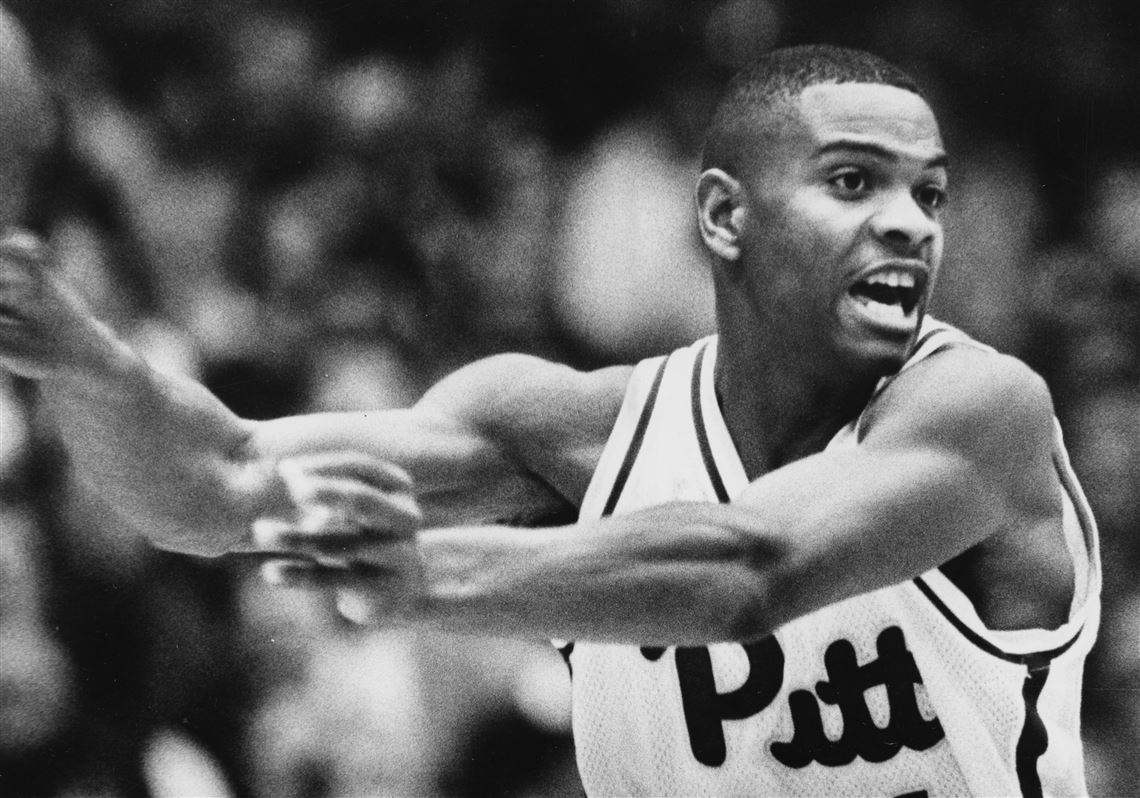

The sequence of Pitt guard Sean Miller leading a fast break punctuated by a thunderous, backboard-shattering dunk from Jerome Lane lasted only three seconds, but that one play has displayed a staying power few in that moment could have anticipated. It turned a 34-point rout against a middling Providence team on a cold January night into perhaps the most iconic game in the history of Pitt basketball.

Thirty years to the day that it occurred, the dunk still captures the imagination of those who witnessed it inside the cramped confines of Fitzgerald Field House and those well beyond it.

“It was just an occurrence, the spontaneity of the moment,” said broadcaster Bill Raftery, who called the game that night for ESPN. “I don’t think anybody in the building ever saw a backboard come down live. I think everybody may have seen [Darryl] Dawkins do it or something like that in high school. It was just an unusual occurrence. I think that’s just the shock of the moment. It was one of those moments in time that just hit you.”

With Pitt leading, 8-5, Miller got a steal off an inbounds pass and sprinted up the court. With teammate Jason Matthews well in front of him to his left and with a streaking Lane to his right on a three-on-two break, Miller dribbled up to the top of the key, at which point a defender bit. Miller, without looking, dished it in stride to Lane, who rose, cocked the ball back and threw down a vicious, one-handed tomahawk dunk.

From virtually the moment his hand hit the rim, the backboard disintegrated, breaking into thousands of small pieces that Lane said in a 2011 interview came down “like snow.” The rim stood as a survivor of the wreckage, seemingly hanging by a thread. As the crowd rose to its feet and Lane strode away from what remained of the basket, Raftery belted out a line forever linked to the play – “Send it in, Jerome!”

“I brought him over to the sideline and was trying to get glass shards out from his hair, all through his body, his jersey,” said Tony Salesi, Pitt’s head men’s basketball athletic trainer. “It was amazing the amount of glass that was all over him.”

The broken backboard caused a 32-minute delay, a time in which a replacement basket was brought in from a storage area in the arena. Without a studio show to cut away to, Raftery and broadcast partner Mike Gorman pulled Golden State Warriors coach and vice president Don Nelson, who was scouting that night, from the crowd and talked to him for about 20 minutes.

“I think we went through every possible college player that might make the NBA,” Raftery said with a laugh.

To best understand the impact of the dunk and why it still resonates, one needs to understand the era that birthed it.

Although a crucial component of ESPN’s early rise, college basketball, like all sports, wasn’t as readily accessible as it is today, when most any Division I game is available on some kind of platform. At that time, the network’s Big Monday broadcast would regularly feature a Big East game, giving a school such as Pitt a national platform. Without a slew of other options, if someone was a college basketball fan, they were likely watching. That scarcity could turn a play that could quickly fade in the vast, oversaturated abyss of the internet today into a firmly entrenched topic of national conversation.

Then, of course, there is the sheer ferocity and absurdity of the play itself. In 1978, the NCAA first used the breakaway rim, which has a hinge and spring in it, allowing it to bend down when a player dunks and withstand the weight and force of such plays. The innovation, ostensibly, would make backboards shatter-proof.

Lane had other ideas. At 6-foot-6 and 232 pounds, he wasn’t an extraordinarily large figure like many others who have demolished baskets, men such as Dawkins and Shaquille O’Neal. But inside that frame was every bit of strength and power there could be. As a sophomore in 1987, he became the shortest player in nearly 30 years to lead the country in rebounding, with 13.5 per game. His foreboding presence near the basket was even immortalized in song. In a self-produced 1986 rap video called “Pitt on the Rise,” Lane’s teammate, Demetreus Gore, had two bars in which he said “gettin’ all the boards like he is insane / is that board-crashin’ brother Je-Rome Lane.”

“Jerome was big; if anybody could have done something like that, I think all of us felt like it would be him,” Miller said recently. “He was one of those guys who rose to the moment. The bigger the game, the bigger he played.”

The dunk, in more ways than one, always remained with Lane. Teammates have joked in the past that Lane spent the rest of the season trying to re-create the irreplicable. He finished the season as an all-American and was a first-round NBA draft pick later that year, the start of a 12-year professional career. So much was made of the dunk, Miller said, that many forgot what a great all-around player he was.

His son, Jerome Lane Jr., was even recruited by Pitt as a football player coming out of high school, but he opted to stay home and play for Akron, in some part to create an identity for himself separate from his father, just as he had done when he attended Firestone High School instead of his father’s alma mater, St. Vincent-St. Mary.

The shadow of the dunk looms large, but Lane largely embraces it, particularly when it can provide a connection to his celebrated past. Raftery said Lane’s son at one time didn’t believe his father could play basketball until he was shown the video clip.

“My legacy is just a dunk,” Lane said in a 2013 interview with ESPN. “It’s been 25 years. I’m glad they still know me for something.”

Multiple attempts to interview Lane for this story were unsuccessful.

The dunk’s two most prominent figures, Lane and Raftery, keep in touch periodically and are sometimes brought together for what amount to reunions. In the past, Lane has thanked Raftery for making him famous with his call, with Raftery responding by saying it’s the other way around.

For all the Pitt players involved, the play stays with them in some kind of way, even if it’s only something to be commemorated every time a round-numbered anniversary comes around. They’re joined together not only as teammates, but by history.

“There was no warning,” Miller said. “You were on a two-on-one, a play that happens almost every day. You see guys make catches and finishes and dunks, but there’s no warning when that happens. When it happens, it stays with you. That’s why we’re on the phone 30 years later.”

First Published: January 25, 2018, 1:00 p.m.