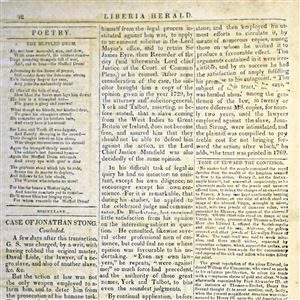

Pittsburgh Post-Gazette publisher and editor-in-chief John Robinson Block is proud to have in his collection of newspaper artifacts an extraordinary piece of Black history: an original copy of the Liberia Herald from May 6, 1830. In commemoration of the last weekend of Black History Month, we are happy to share words and images from this document, and from Liberian history.

The founding of Liberia is a forgotten and complicated piece of African-American history. In 1816 and 1817, two norther clergymen, Robert Finley and Samuel John Mills, founded the American Colonization Society, with the aim of creating a new colony in West Africa for free Black Americans.

The society came to be supported both by some abolitionists, who saw it as a way to give free Black people a new start and to encourage the end of American slavery, and by some slaveowners, who saw it as a way to rid themselves of troublesome freedmen.

But the society also attracted scorn, especially from Black Americans themselves. Frederick Douglass famously denounced the movement as a way for the United States to absolve itself of its sins without resolving them: “Shame upon the guilty wretches that dare propose, and all that countenance such a proposition. We live here — have lived here — have a right to live here, and mean to live here.”

For Douglass, as well as white abolitionists like William Lloyd Garrison, Black Americans were Americans, first and foremost, and they deserved to be treated fairly in their true homeland, not shipped off to another continent.

But others saw in the Liberia project another deeply American concept: the freedom and excitement and risk of starting something brand new, of building from scratch.

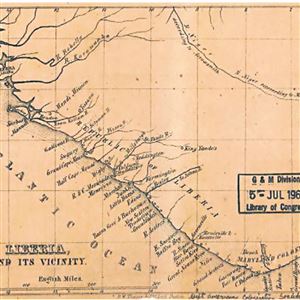

In the end, more than 4,500 free Black Americans emigrated to what became Liberia from 1820 to 1843; fewer than 2,000 survived those early years. The journey itself was arduous — as the note in the Liberia Herald indicates — and the conditions on the West African coast were harsh. Still, the newcomers persevered, and in 1847 declared independence from the country that had dispatched them, the United States.

The Liberian Declaration of Independence is a remarkable document, clearly modeled on its American counterpart. It was written by Hilary Teague, a native of Virginia who went on to become a senator and secretary of state in the new Liberian government.

In the declaration, both contemporary and modern readers can see the same, deeply human yearning for freedom that inspired the American Founders roughly seven decades earlier. But for the Americo-Liberians, it was the United States that had systematically denied them their natural rights — and not just through slavery, but through other legal and social restrictions.

“All hope of a favorable change in our country was thus wholly extinguished in our bosoms, and we looked with anxiety abroad for some asylum from the deep degradation.”

It is a tragic irony that continues to this day: the denial of precisely the rights and aspirations that inspired this country to some groups within it. The Liberian Declaration of Independence bears witness to this sad truth in a way few other documents do.

The subsequent history of Liberia has been no less complicated than its founding. While the United Kingdom recognized the nation’s independence shortly after the declaration, it took the American Civil War for the United States to do the same. Those hard feelings eventually faded, and the U.S. had close ties with its offspring for much of the 20th twentieth century.

This was a time of stability and prosperity for Liberia, at least compared to its African neighbors. It was the only African nation to retain its independence during the mad scramble for Africa, when the continent was partitioned among European powers.

Meanwhile, the Americo-Liberians, perhaps re-enacting the same irony that drove them from North America, treated the indigenous Africans within their borders — a significant majority — as second-class citizens. The resentments eventually boiled over in 1980 with a revolution against the Americo-Liberian elite, followed by decades of political chaos, from which the small country has never fully recovered.

Liberia has a relationship to the United States, and to Black history, unlike any other nation on Earth. We are proud to have a small piece of this history with us, and to present it today.

First Published: February 27, 2022, 5:00 a.m.