African Americans may — at first blush — seem ungrateful for the well-meaning charity of wealthy whites. The reasons for the rejection of their noblesse oblige gestures are ably explained by the fact-based revelations in a new book by David Montero, a journalist and former producer for PBS’s “Frontline.” “The Stolen Wealth of Slavery: A Case for Reparations” debunks centuries-old myths about the supposedly race-neutral American meritocracy.

In 1962, the renowned African American rhythm and blues crooner Ray Charles famously sang: “The old saying that them that’s got is them that gets is something I can’t see. If you got to have something before you can get something, how you get your first is still a mystery to me.”

Montero’s bold revelations tackle that mystery, of white Americans’ wealth versus Black Americans’ relative lack thereof.

White history’s surprises

The author tracks to slavery the great wealth by which some well-known banks, corporations and individuals are enriched today. He shows that the North made the most from slavery. Many northerners supported slavery even during the Civil War because it was in their self-interest to do so. They used the fortunes they’d made from slavery to make even more money in the decades that followed.

There are surprises in Montero’s history.

The Broadway blockbuster musical “Hamilton” and the Hamilton house in Harlem — the center of Black America — led some to the belief in Alexander Hamilton as an American egalitarian. The celebrated first Secretary of the Treasury came to despise slavery after witnessing mistreatment of slaves in his childhood Caribbean island environment, but as Montero documents, American immigrant Secretary Hamilton enslaved several fellow Americans.

Alexander Hamilton, Thomas Jefferson, Benjamin Franklin and several other American Founding Fathers were freedom lovers for whites, yet their real belief about freedom is betrayed to history by their slaveholding of Blacks.

Another surprise is the story, examined in painterly historic detail in Montero’s account, of how Pittsburgh’s beloved Hillman billionaires and philanthropists “got there first.” In 2017, venture capitalist and businessman Henry Hillman was reported by Forbes magazine to have a net worth of $2.6 billion.

At their deaths in 2015 and 2017, respectively, Elsie and Henry Hillman were among the greatest names in Pittsburgh philanthropy. The Hillman Library at the University of Pittsburgh and the Hillman Cancer Center on Pittsburgh’s Centre Avenue bear powerful testimony to both the generosity and wealth behind the Hillman name.

In her political and philanthropic worlds, Elsie Hillman embraced both Republican candidates and Black involvement in the GOP. She partnered with African American attorney Wendell Freeland to engage more African American Republicans.

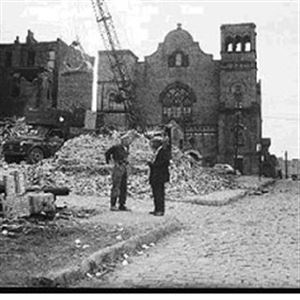

And the Hill House community center that is popular in the Black Pittsburgh Hill District neighborhood, made famous by Black Pittsburgh playwright August Wilson, benefited from both Elsie Hillman’s board service and charity. She was also a Republican National Committee member from 1975 to 1996.

A Pittsburgh bounty

Still worth billions today and still mostly based in Pittsburgh, the Hillman progeny have 18 family foundations that seemingly selflessly dispense millions annually to beneficiary causes they encourage, mainly in the steel city. Yet, according to Montero, the origin of the family fortune dates to the enormous unpaid productivity of African American Hillman slaves in Kentucky, Tennessee and Alabama.

In the 1840s, Henry Hillman’s ancestor Daniel Hillman, Jr., worked some 250 African American slaves in his iron works. This unpaid slave labor rendered the Hillmans rich ... staggeringly rich.

Today, one can scarcely imagine that African American slaves in the South made possible the financially bountiful Hillman existence handed down the generations through trusts, wills and luck in the lottery of birth.

Long before the Montero polemic, I knew African American wealth was stolen by those who enslaved Black folks or facilitated their bondage, and that justified, indeed required, compensatory reparations payment. The unanswered question for me was the issue of rightful beneficiaries in a changed and changing world of mixed-race Americans.

Decades ago, I was part of a team that tried to recruit the noted African American economist William “Sandy” Darity and his collaborator, renowned folklorist A. Kirsten Mullen, to Syracuse University. They could not be lured out of North Carolina.

Late last year, a CNBC documentary, “How reparations to Black Americans could close the racial wealth gap” featured the pair discussing reparations and solving my qualifications-for-reparations dilemma. They built on their book, “From Here to Equality.”

The payment due

Darity and Mullen advocate compensation for those whose ancestors were American slaves. They situate America’s indebtedness to descendants of American slaves — not to Blacks, not to Afro-Caribbean people, not to Africans, but to those whose forebears were American slaves. The couple establishes the payment due at $14 trillion.

The nation has the money, much of it built on the work of slaves. The 2006 merger of Pittsburgh’s Mellon Financial, co-founded by white supremacist Thomas Mellon, and Bank of New York, founded by enslaver Alexander Hamilton, created an entity, BNY Mellon, that today has some $45 trillion in assets ‘’under custody,” whose origins include the laundered productivity of unpaid stolen labor of African American men, women and children.

Robert Hill is an award-winning Pittsburgh writer and communications consultant. His previous article was “The artist who left a racist Pittsburgh and became a major painter somewhere else.”

First Published: May 30, 2024, 9:30 a.m.