She was impressively single-minded, the communications person for an industry group I talked with a few days ago. She insisted that only her industry’s favored terms were correct, accurate, scientific, true and objective. No other words should be used. People who used other terms were prejudiced against her industry, as well as being incorrect, inaccurate, unscientific, etc.

Being used to the give and take of normal human conversation, and being out of practice in dealing with pr flacks, I was at a disadvantage in trying to point out that her terms weren’t the only correct, accurate, etc. terms for the things we were talking about. People with other points of view would naturally use different words than she wanted them to use. They weren’t wrong. They just disagreed with her.

Words matter

She never wavered. She stayed absolutely on message. But at least she paid attention to the words and knew to fight over them. Of course, she did it not to tell the truth but to establish one meaning among the possibilities and push the others out of use.’

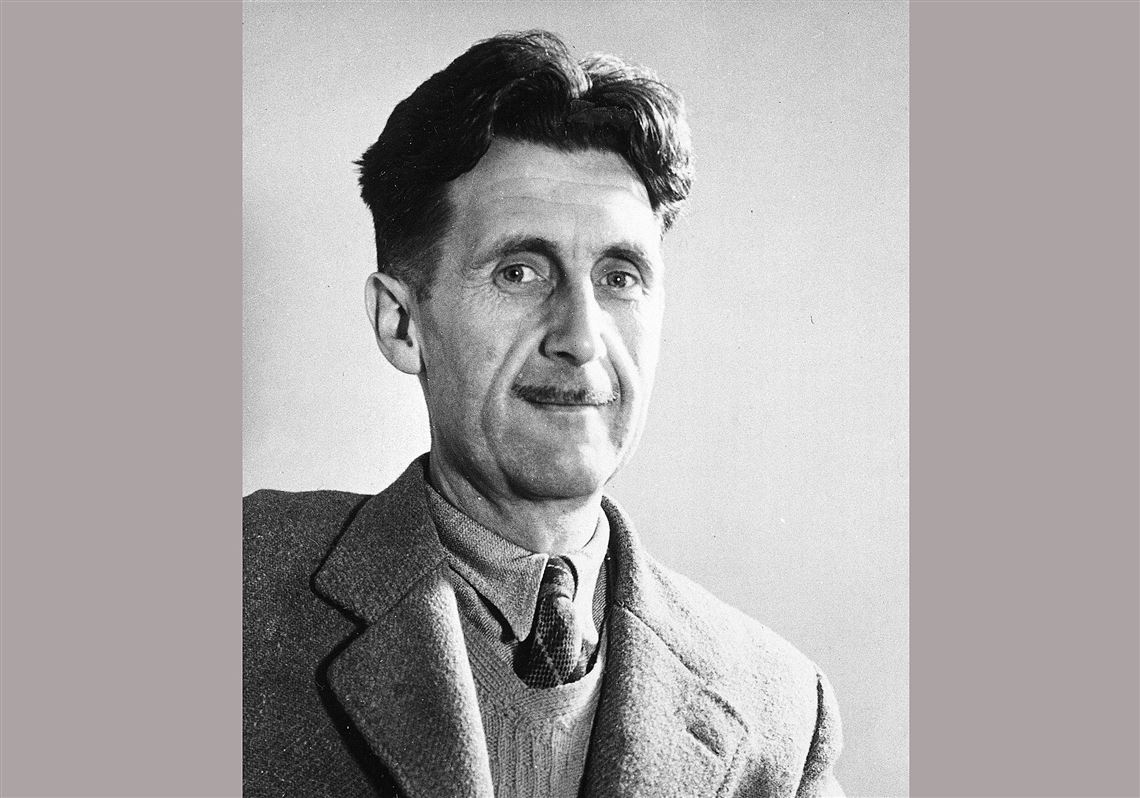

It’s very useful to push words out of use. That’s essentially to destroy them. “It's a beautiful thing, the destruction of words,” an expert in language says in George Orwell’s novel “1984.” He’s helping to compile a new dictionary of “Newspeak,” the language the book’s totalitarian regime imposes on the people to keep them from thinking clearly, because thinking clearly might lead to rebelling.

“Don’t you see,” he told someone he cornered in the cafeteria of the government agency called the Ministry of Truth, “that the whole aim of Newspeak is to narrow the range of thought? In the end we shall make thoughtcrime literally impossible, because there will be no words in which to express it. … Every year fewer and fewer words, and the range of consciousness always a little smaller.”

That’s one very big problem with our political speech. Too many people destroy words in a particularly effective way: by giving people a reason to reject speech they don’t want to hear.

One of those words used all the time is “extremist” for someone you disagree with. (Also related words like leftist, rightwing, woke, fascist.) If you successfully label someone an extremist, no one has to listen to him or take seriously anything he has to say. Everyone should act as if he didn’t exist.

Compounding the problem is that so many people destroy their own words by using them so badly and dishonestly. Donald Trump, obviously for one. As I’ve said before, he lies the way the rest of us breathe. He could recite the Gettysburg Address and my instinctive reaction would be to disbelieve it. But to be fair to Mr. Trump, I don’t trust Democratic politicians much more. They’re not in a line of work conducive to rigorous truth-telling.

Who’s the extremist?

What does “extremist” mean anyway? We don’t have any objective, shared way to determine where is the line between going far out and going too far out — the line between the acceptable radical and the unacceptable extremist.

Because so many people in public life so promiscuously accuse each other of being extremists, all “extremist” means as a public word is “I really really really disagree with that person.” Or maybe more simply, “I’m on this side, not on his side.” Or more crudely, “I hate him.”

We do have a broad consensus on the very extreme extremes, like the neo-nazi and the stalinist and anyone who approves terrorism. Which is something. America will be completely screwed if more than 1 in 10,000 Americans endorse any of those things or if such beliefs become “fringe” rather than “extreme.”

But outside that consensus, as a public word, a word ideologically diverse Americans can use to talk with other each, “extremist” just tells people what political group you belong to, which they probably know already. It does no good.

And how do we defeat him?

How do we talk about people we think extremists? Effectively, in a way to convince people not already on your side?

In our public language as in other things, the golden rule (in its negative form) offers a useful criterion for what we should and should not say. Do not say of others what you would not want them to say about you. You don’t want to be shoved out of the discussion as an extremist, don’t try to do the same thing to people on the other side.

Don’t, unless forced to it, call the extremist an extremist. Name his ideas for what they are and argue against them. Show the world how wrong he is. Let them to see how far out he is. If you want to drive someone out of the public square, show everyone else that he’s very wrong and that his ideas are not only wrong but dangerously wrong. That way you might actually change someone’s mind.

David Mills is the associate editorial page editor for the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette: dmills@post-gazette.com. His previous article was “Grim, pessimistic, unsentimental wisdom to live by from the ancients.”

First Published: September 5, 2023, 9:30 a.m.