Generally, when an audience member speaks up at the theater, it’s not what you want. But when Elaine Melnick, 87, shared a memory of her Hill District youth this past Sunday at the Pittsburgh Public Theater, it was magic.

We’d all just seen “Indecent,” a powerful story depicting the days of the Yiddish theater, when immigrant Jewish playwrights and players brought entertainment to their struggling brethren. Eric Lidji, director of the Rauh Jewish History Program and Archives at the Heinz History Center, had followed the performance with a talk about how such fare played in Pittsburgh.

Mrs. Melnick raised her hand to share her tale of being a scared little schoolgirl pulled onto the stage at the old Lando Theater on Centre Avenue during the throes of the Great Depression.

The theater was on the 1800 block, she told us. She knew that because her dad’s business was at 1911 Centre near the corner of Dinwiddie.

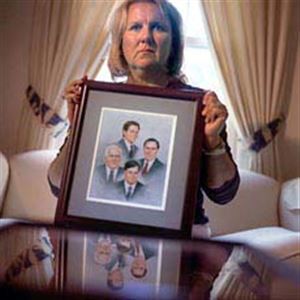

“My mother loved going to the Jewish theater,” she recalled again when I visited her and her husband Milt at their home in Squirrel Hill Monday afternoon. (They’ve been married 68 years. A lot of people are starting to believe their marriage might last.)

Her stepfather, Isaac Rosenberg, had to work nights running The Silver Bar, which he’d opened when Prohibition had ended a few years before. (“Sandwiches of all kinds. Beers — wines — liquors,” said a classified ad for the place in a June 1937 Post-Gazette.) Mr. Rosenberg had done some bootlegging on the sly before that. (“We had in our house, we had secret passageways that were so interesting,” she told me of their place in Homewood. “From the cupboard you could go down. There were steps. And they would take you into the basement, out to the garage.”)

Anyway, her widowed mother, Rose, had married this widowed man not that long before this night at the Lando. Little Elaine couldn’t have been much more than 8 when she learned how Yiddish theater worked.

“Whenever they needed child actors, they didn’t ask, ‘Would you like to go on the stage?’ They said to my mother [and here Mrs. Melnick shared some Yiddish that she translated as] ‘Come and take your daughter up on to the stage and I’ll bring her back to you afterwards.’ My mother says, ‘Take her. It’s OK.’

“You know, those years they didn’t worry about children like they do today.”

Some other kids had been pulled up on stage, too, and she remembers being scared looking back into the crowd. “Thank God we didn’t have to talk because I know the words wouldn’t come out of my throat.”

None of that kept Elaine and her mother from going back. In ensuing productions, Elaine was brought to the stage two or three more times. “It got to be old hat after a while.”

The hard times that surrounded those oases of entertainment make her memories vivid. Her story could be a play itself: After Elaine’s natural father, who’d had older children from a previous marriage, had died, the oldest child soon handed his stepmother a chicken from his job at a grocery store for the night’s supper — and said that was the last thing he’d provide. Their previous family was no more. He was leaving and so were his sisters. Elaine and her mom were dirt poor and on their own.

Rose Waldman was crying in the living room of their rowhouse when a neighbor came by. “Oh, Mrs. Waldman,” she asked. “What’s the matter with you?”

“I’m alone and I have no money,” she answered. “The rent’s due in a week.”

The woman’s husband, a tailor, was sent over. “Mrs. Waldman, don’t worry,” he assured her. “I’m going to find you a husband.”

The next night a man called on the party line to ask her mother out to dinner. “And where did he take her? He took her to Klein’s.” It was the early days of that groundbreaking seafood restaurant at 330 Fourth Ave. Downtown, with its huge neon lobster that lured diners until 1992 (and is now displayed at the Heinz History Center).

“My mother came home and said he was very nice. And the next day we get a package. And inside was a little dress for me. And my mother said, ‘That’s it. I’m not looking any further.” She married this good man.

Mrs. Melnick had more stories. She had a couple about her handsome, much older stepbrother, Sam, a lady killer when he wore jodhpurs and rode horses in Schenley Park. He’d be killed in action in Germany on April 15, 1945, just a few weeks before V-E Day. I found Lt. Samuel Rosenberg’s obituary in the June 1, 1945, Pittsburgh Sun-Telegraph.

Mr. Lidji, the history center archivist, said, “We move through our days with this assumption of what everybody knows, and there’s a feeling of permanence to that, like everyone will always know it. But it’s actually very ephemeral.

“Two or three generations away, that stuff, if it wasn’t documented in some permanent form, it just disappears.”

A bit of Elaine Waldman Melnick’s story is here now. Maybe it will be found found again some decades hence, and yet I find myself wondering how much will be lost if local newspapers disappear forever.

Brian O’Neill: boneill@post-gazette.com or 412-263-1947 or Twitter @brotheroneill

First Published: May 2, 2019, 4:00 a.m.