If you were unable to escape the news on crime and punishment in America before the elections, you might have been in a constant state of fear. Reporting on crime went through the roof, creating a looming sense of danger, detaching us from our neighbors, friends — even our families. Most people expected a red wave of tough-on-crime candidates ascending to power.

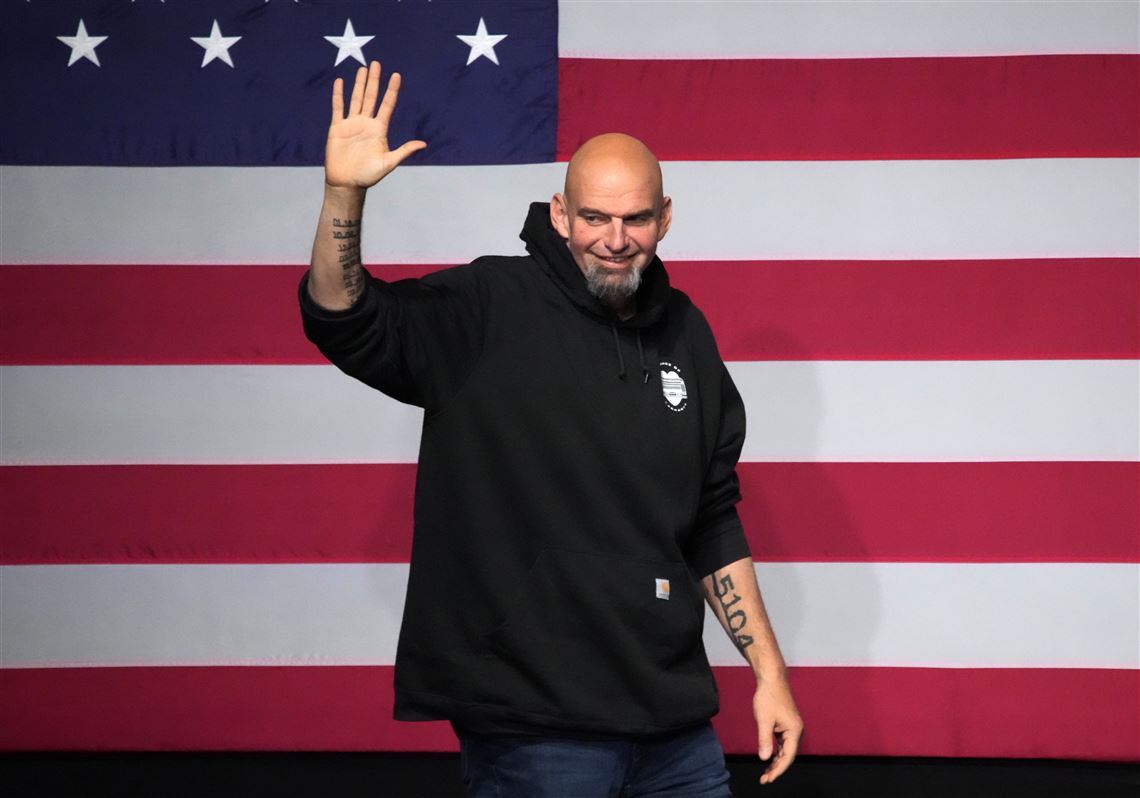

But voters had other ideas: in New York, the gubernatorial tough-on-crime candidate bit the dust; in Pennsylvania, Mehmet Oz’s attacks on John Fetterman for his support of commutations, safe injection sites, and reducing prison populations left voters as cold as a pile of day-old crudites. In Colorado, Elisabeth Epps, a prison-abolitionist, handily won her election.

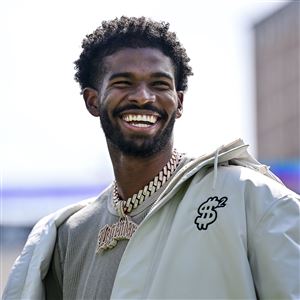

In Los Angeles, Kenneth Mejia, a candidate for city controller known for his transparent criticism of bloated police budgets, sailed to victory. In a race for a city council spot in that same city, Hugo Soto-Martinez prevailed against his heavily carceral opponent and incumbent Mitch O’Farrell, who displaced people without homes and called for increased policing in his district.

A sheriff in Bristol County, Massachusetts known as the “Arpaio of the East” lost his seat, correctly conceding that, “people are just ready for change.” In Minneapolis, a city at the heart of the struggle over how we address harm, Mary Moriarty, a former public defender, became the top prosecutor in the county.

Similar victories for reformers were seen in Austin as well as central Texas and Iowa. A candidate in Oklahoma who, in reflecting on a recent police shooting of a 15-year-old in his jurisdiction said “I would have shot him myself,” lost to a candidate who ran on being less cozy with the police department. The list goes on.

We should have seen it coming, and some did. Recent polling from Fwd.us showed that 80% of voters support criminal legal reform and 58% were more likely to vote for a candidate who does as well. They’re not wrong: if policies rooted in bias that punish some in the name of public safety actually worked, we’d be the safest country in the world. But we’re not, and after decades of throwing more and more money into the pockets of police and prosecutors, voters are sick and tired of divisive tactics and are ready for change.

As a person who has personal first hand experience with both victimization and incarceration I know that we can do better and Ruth Wilson Gilmore agrees. She once said, “Abolition is about abolishing the conditions under which prison became the solution to problems, rather than abolishing the buildings we call prisons.”

It’s true, the things most associated with increasing public safety are not tough-on-crime policies. Housing, a livable wage, community connections, and access to healthcare are all correlated with lower crime, greater health, greater stability, and economic mobility. In other words, a lot of bang for our taxpayer bucks. Prisons and jails strip these things away. The sheer quantity of research demonstrating that care is more effective than

cages at making our neighborhoods safer and more prosperous is tremendous; making it hard to avoid the conclusion that the only reason people still run on “tough on crime” policies is that they’re either personally retributive or wildly uninformed.

Sadly, many candidates still remain in the category of retributive or uniformed. After engaging in extended hand-wringing about the word “defund,” they pushed dollars towards tough-on-crime, centrist candidates they thought were stronger for their pro-carceral positions.

One hopes that with the benefit of hindsight, these party leaders would take a hard look at who won in red, blue, and purple districts across America and reconsider whether 1990s racist criminal justice policy is still something they want to invest in. Voters have gotten smarter — so when will party brass?

Elesha Nightingale is the founder of The Uplift.

First Published: November 18, 2022, 5:00 a.m.