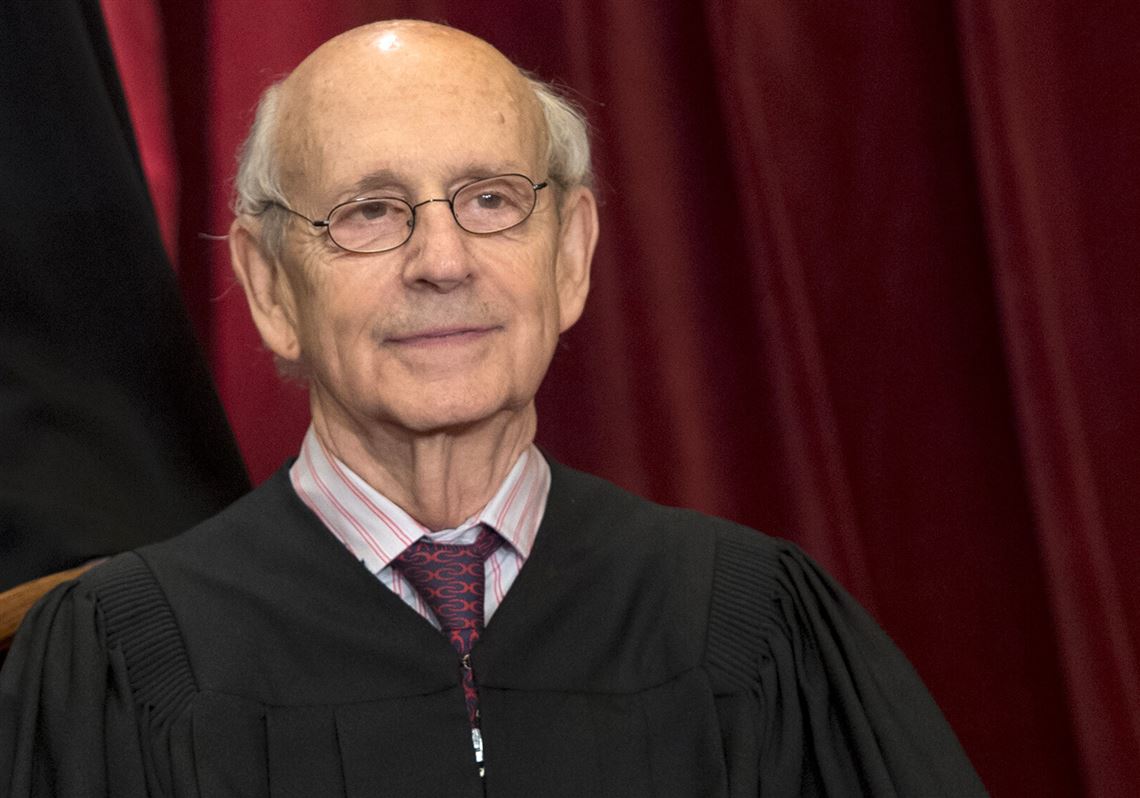

Justice Stephen Breyer’s decision to retire from the Supreme Court at this moment in history — as he approaches the age of 84 during a politically charged, highly polarized time in American government — is as thoughtful and orderly as his own legal and judicial career. Breyer is often viewed as a poster child of the court’s liberal wing. In fact, however, he has been a moderate on many fronts (especially by today’s standards), nudging the court toward consensus on many of the most sensitive and tricky issues of the past decades. A Harvard Law School professor by trade before he ascended to the bench, Justice Breyer taught administrative law during my years there and was known by students as intellectually rigorous, quirky and funny with a dry delivery. Above all, he was someone who cared deeply about the legal institutions to which he dedicated most of his career.

As a young lawyer, Breyer served as an assistant prosecutor to highly principled Watergate special prosecutor Archibald Cox, whom he considered a role model and a valued mentor. When I was privileged to work on Cox’s biography and reached out to interview his legal colleagues, Justice Breyer took my calls without fail, answering his own phone in the Supreme Court and chatting about a wide range of topics. He would become particularly animated when he discussed the importance of public service and the vital role that lawyers and judges must play in giving life to the words of the U.S. Constitution.

Breyer believed fervently in the living, breathing nature of the Constitution as a document designed to adapt to the ages. He even wrote books on that subject. Yet Breyer has always been a pragmatist. He cut his teeth as chief counsel to the Senate judiciary committee under the leadership of Sen. Edward M. Kennedy, a Democrat from Massachusetts. Breyer’s apolitical, non-partisan approach to guiding that committee earned him respect and admiration from both Democrats and Republicans alike in the U.S. Senate, allowing him to be confirmed for the Supreme Court by an overwhelming bipartisan vote of 87 to 9, something that would be unimaginable in today’s fractured Washington.

A true intellectual leader from the moment he joined the court, Justice Breyer still takes delight in playing law professor during oral arguments, whittling away at counsels’ arguments and boring down to the crux of the issues to arrive at reasoned solutions. He has written opinions defending passionately the rights of free speech and freedom of religion, decrying partisan gerrymandering, noting the virtues of affordable health care, and supporting affirmative action, at least within certain boundaries. Yet at times, he has also sided with his conservative colleagues, including on criminal/search and seizure issues when he believed practical rules were necessary to achieve constitutional consistency. Similarly, he has tilted toward the middle ground and joined conservatives on matters dealing with obscenity, drug regulations, establishment of religion, and other areas where he has staked out moderate positions.

Perhaps not coincidentally, Justice Breyer is stepping down just as President Joe Biden kicks off his second year in the White House. In many ways, Biden and Breyer reflect mirror images of each other, albeit ensconced at the top of different branches of government. They possess the same old-fashioned values when it comes to government service and the importance of the rule of law, having grown up in the 1960s during an era of idealism sparked by President John F. Kennedy and others who inspired many young lawyers to dedicate themselves to this calling. Both are undramatic people who favor practical resolutions. Breyer doubtless feels that his time now has come to step down from the marble steps of the nation’s highest court, in part because he understands he’s mortal and because his close friend Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg died suddenly in 2020 without time to plan a fitting exit. Yet almost certainly Breyer is leaving now because he knows Biden is likely to nominate someone who will keep alive many of his own jurisprudential views and cherished constitutional principles.

Both Biden and Breyer find themselves holding high positions in Washington at a time when the liberal wing of the Democratic Party is moving more dramatically to the left and the conservative wing of the Republican Party is moving more aggressively to the right. Yet both men have always felt more comfortable occupying the middle, a place that most Americans still occupy despite the hyper-partisanship, discourtesy and fractionalization that now define American politics. Breyer is content to leave the greatest legal job in the world at this moment, during the administration of this particular chief executive, for a reason. He is hoping that, long after he has left, his replacement will help return the court and the American system of laws and justice back to the paramount place in our society that Breyer believes, so deeply, they must occupy. At least, he would add, if our democratic system is to function as the founders of this country once envisioned.

Ken Gormley is president of Duquesne University and a constitutional scholar who has written extensively about the Supreme Court and its history.

First Published: January 27, 2022, 5:20 p.m.

Updated: January 27, 2022, 5:45 p.m.