In a recent episode of his talk show, John Oliver acknowledged that “it can be easy to ignore” the problem of the coronavirus in prisons. But whether or not the problem has been ignored, it’s a simple fact that U.S. prisons and jails have been ravaged by the virus, and the results are becoming increasingly dire.

As of June 16, over 68,000 U.S. prisoners have tested positive, while hundreds have died. In fact, the five largest recorded outbreaks in the country have all been in prisons.

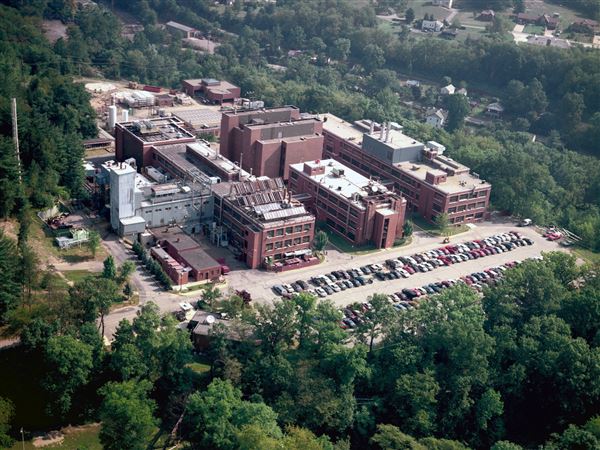

But perhaps our most conspicuous prison — the American detention camp at Guantanamo Bay, Cuba — has yet to publicly report a case of coronavirus among the 40 men who remain there. However, a coronavirus outbreak at Guantanamo, among an aging and increasingly sick population, would be extremely problematic — for both the detainees and the American public.

Retired Brigadier General Stephen Xenakis, a former Army doctor, was so concerned by the situation that he recently wrote to members of Congress, saying:

“Some detainees have demonstrated serious preexisting illnesses that predispose them to poor outcomes if they become infected and require intensive care…the medical treatment facility has not been equipped to treat and manage severely sick and complex patients. The spread of COVID-19 among the detainees could quickly overwhelm the capacity of the facility to treat them adequately and safeguard against an uncontrolled contagion across the base.”

Congress is becoming increasingly worried about the potential for a “significant” coronavirus outbreak at Guantanamo, so much so that over a dozen senators sent a letter to the Pentagon seeking answers to what the plans were in case a detainee became sick. To be clear, those medical concerns are not caused by my colleagues-in-arms deployed to serve there. To the contrary, as stated by Dr. Xenakis, “[the] limitations are not the fault of front-line military medical personnel that are doing their best under difficult circumstances. Guantanamo was designed for short term detention operations, and its healthcare infrastructure was built accordingly.”

Still, consider the ramifications if one or more of the remaining detainees die as a result of an infection. For many victims of the crimes they are charged with, it would permanently preclude the prospect of a verdict and judicial finality, which they’ve been waiting on for nearly 19 years. After years of pain and suffering, victims and their families would forever lose the opportunity for a meaningful end in a courtroom. Conversely, many of the detainees would have no chance to prove their innocence, return to their homes, or see family members and children they’ve been separated from for years. Either way, justice is denied.

Furthermore, imagine the galvanizing effect a coronavirus death would have on violent extremist groups around the world, who are exploiting this pandemic to rebuild their strength and entrench for future attacks. A Guantanamo detainee dying from coronavirus would be major international news, and groups might use that individual’s death as a rallying call while drawing additional attention and ire to the now-two decade-old legal quagmire of the Military Commissions.

To be fair, the leaders in charge of the detention center have taken some simple measures to protect the lives of the guards and detainees. For instance, to visit the island now requires multiple quarantines, and a single round-trip visit could take close to two months. However, these efforts have further eroded the goal of getting to trial, as cases have been postponed and defense attorneys are unable to effectively communicate with our clients. In short, we are unable to do our jobs, which means this process cannot move forward.

For some detainees, these developments have taken ongoing trial proceedings and pushed them further down the road. This is especially true in the case of the alleged 9/11 plotters, who simultaneously face the prospect of not even having a judge to oversee their case, which has been in pretrial proceedings for nearly a decade.

For other detainees, it has delayed any prospect of getting into court to face charges or present a defense. My client, a Malaysian man named Nazir Bin Lep, was severely tortured for three years, and has been detained since 2003. He has been in prison for most of his adult life, but has never been convicted of anything, was never a bona fide member of al-Qaida and never planned or carried out any attacks on anyone, much less 9/11 or any other attack on our country. His crime was allegedly being part of a Southeast Asian terrorist group called Jemaah Islamiyah, but the evidence of his involvement with their activities is limited at best. Even if the allegations were true, his treatment has clearly lacked the due process and fair justice that defines our legal system.

Of course, all of this incarceration comes at a cost. The government has spent billions of dollars on detaining the individuals in Guantanamo, including over half a billion last year alone. My client, who has never even been accused of participating in an attack on America, has cost the government in the neighborhood of $200 million. One might guess that money could have been spent in a variety of other ways far more valuable to Americans right now.

As a defense attorney with the Military Commissions Defense Organization, our mission isn’t to avoid justice — it’s to achieve it. And coronavirus has delayed that justice, which is already decades behind schedule. The risks and costs associated with continuing that delay are untenable, and serve to further emphasize the need to accelerate and resolve these cases.

While Americans obviously have a lot to be worried about these days, we cannot forget about those we cannot see. Similarly, we cannot ignore the men in Guantanamo, no matter how distasteful we may find their alleged crimes. The enduring history of what was done to these men is important for our country, and what we do in response to this latest crisis may have an oversize impact on that legacy.

Lieutenant Commander Aaron Shepard is an attorney in the U.S. Navy Judge Advocate General’s Corps. The views expressed do not reflect the views of the Department of Defense, the U.S. government, or any of its agencies or instrumentalities.

First Published: June 30, 2020, 8:30 a.m.