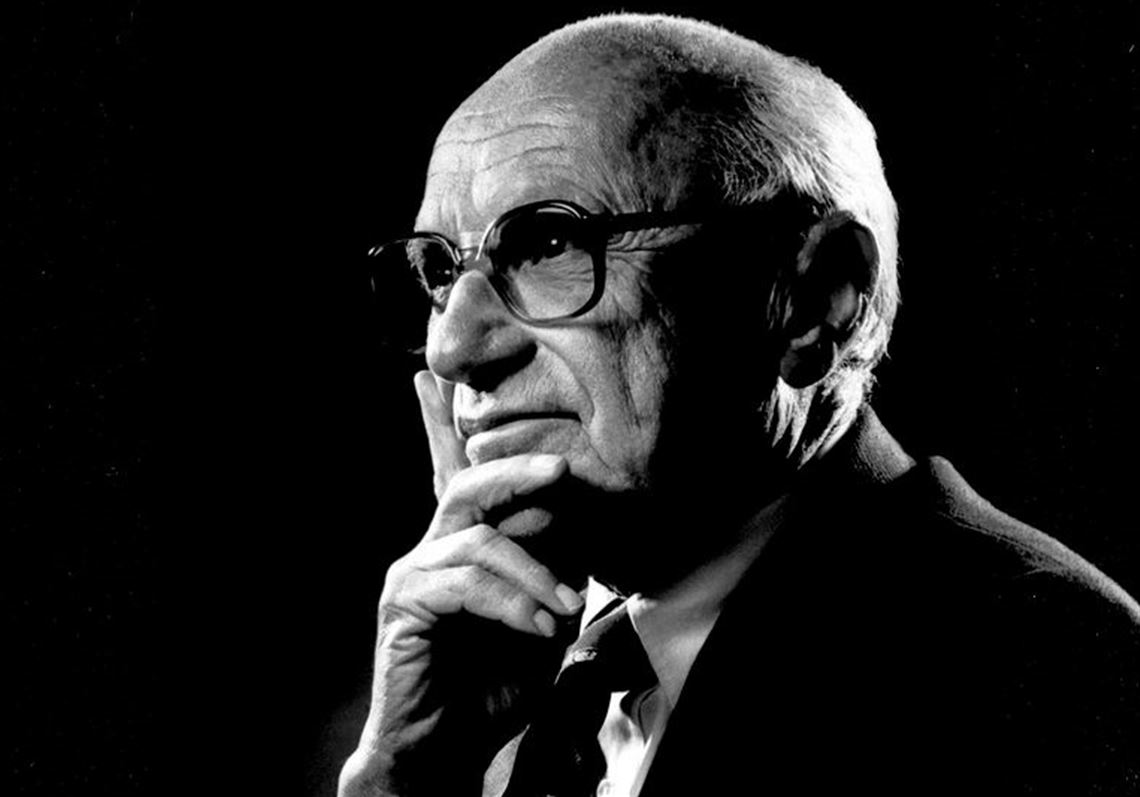

Long ago, famed University of Chicago economist Milton Friedman made several clear-eyed points about the role of corporations in the American free market system. Companies, he said, exist to serve their owners — that is, their shareholders — which means the main responsibility of corporate executives is “to make as much money as possible.” Because that’s what their employers, the investors, want: profits.

As for the idea that companies exist for some separate, higher purpose — to do good in the world — Friedman was direct, but also nuanced in his thinking: “There is one and only one social responsibility of business — to use its resources to engage in activities designed to increase its profits so long as it stays within the rules of the game, which is to say, engages in open and free competition without deception or fraud.”

Friedman — Nobel Prize winner and champion of the private sector, who wrote a book called “There’s No Such Thing as a Free Lunch” — died in 2006. At this moment his free market thinking seems out of fashion.

For years, Business Roundtable — a national group of influential corporations — endorsed the Friedman principle that companies exist primarily to serve their shareholders. On Aug. 19, the group changed its tune, publishing a new statement that says corporations also have four other obligations: to deliver value to customers, invest in employees, deal fairly and ethically with suppliers, and support the communities in which they work. Friedman’s belief is relegated to a fifth obligation: to generate “long-term value for shareholders, who provide the capital that allows companies to invest, grow and innovate.”

The organization, which includes such Illinois companies as Abbott, Caterpillar and Boeing, is reacting to the politics of the moment. The Democratic presidential primary is shaping up to be a debate about the rules of capitalism. High CEO pay, the responsibility of corporations to pay income taxes and the propriety of a for-profit health care industry all are on the docket. Democratic candidates haven’t invoked Friedman as a perpetrator, but it’s not too much to say his ideas are on trial. Which is why corporate America is scrambling to deflect criticism.

Does that mean Friedman’s notions are out of date? No, because his logic is far-ranging. Companies need a path to profitability or they have no reason, or ability, to exist. Serving shareholders is shorthand for saying companies should avoid emotional or nostalgic decisions. In other words, sometimes a 100-year-old widget company needs to stop making widgets, or sell to a competitor, even if it hurts.

Yet companies also contribute social good. The private sector creates jobs, delivers paychecks and generates wealth for the many Americans who own stocks and mutual funds, either directly or via their pension or retirement accounts.

And, as Friedman put it, the role of ethical companies is to engage in activities designed to increase profits. That phrase incentivizes CEOs to invest in employees and communities, and take other actions that could be described as socially responsible. Yet those actions also support the companies’ profitability because they help retain employees, attract customers and develop markets.

Friedman’s larger point was that the private sector has a different function than government has. Companies exist to maximize profits. Whatever good they contribute emanates from that mission.

First Published: August 29, 2019, 8:30 a.m.