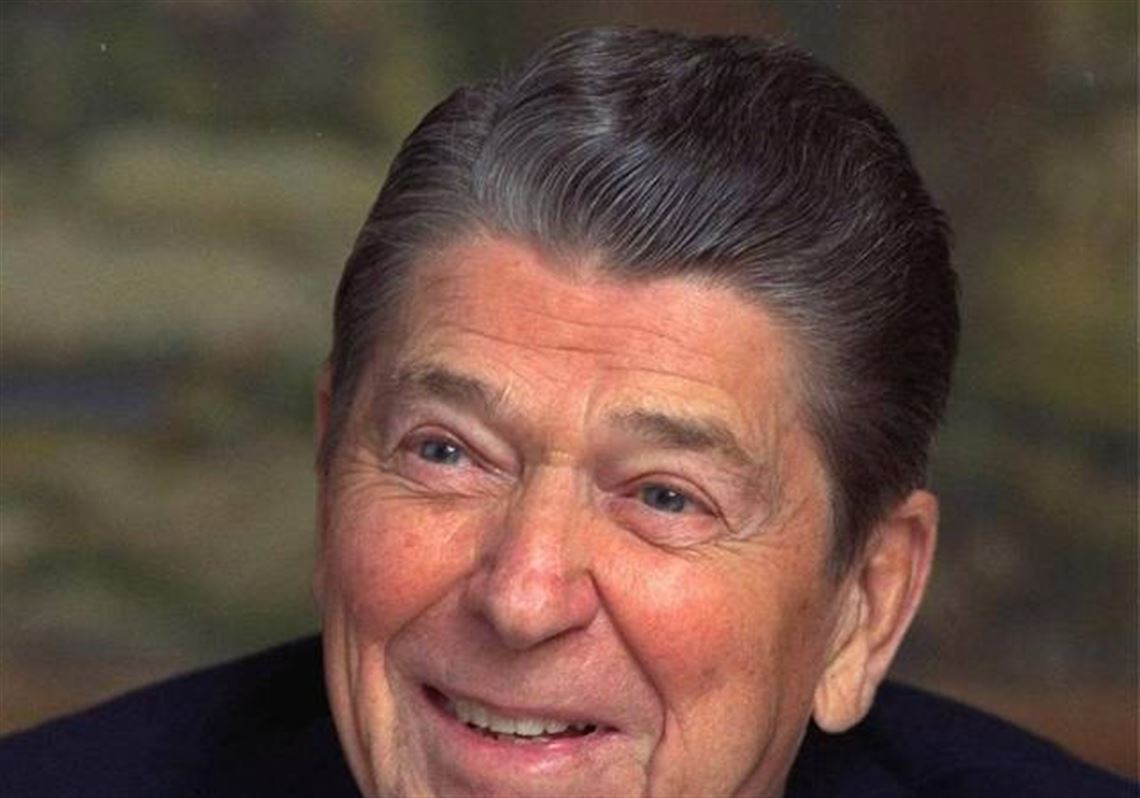

Since before he took office, President Barack Obama has been compared to Ronald Reagan. His progressive supporters hoped he would move politics to the left as much as Mr. Reagan had moved it to the right. Mr. Obama’s last State of the Union address shows that this transformation remains incomplete.

That he has moved public policy in his direction is undeniable. The liberal coalition has expanded, and his party has become correspondingly bolder: His speech showed that, too. The Obama of 2009, making his first address to Congress, felt it necessary to promise to address the “growing costs” of Social Security. The costs of Social Security have indeed grown since then, but the 2016 Obama said he would “strengthen” rather than “weaken” the program, which is what contemporary Democrats usually say when proposing to expand it.

But to leave his mark on American politics for an era, and not just a presidency, Mr. Reagan had to do more than just change his own party or even public policy. He had to move the opposition party in his direction, too. And to do that, he had to be succeeded by an ally.

His successor didn’t have to be someone who inspired the new Reagan coalition, as, indeed, George H. W. Bush didn’t. The successor didn’t have to be someone who had always been an ally: Mr. Bush had run against Mr. Reagan in the 1980 primary and represented a more moderate tendency in the party. To help consolidate the victory of Reaganism, Mr. Reagan’s successor just had to win the election running as a candidate of continuity with him.

In a way, it was even helpful for the successor to lack the political talent of the transformational figure: It showed the opposition that the new coalition could assemble a majority without it.

Mr. Obama and Hillary Clinton now have the same relationship. She evidently does not inspire the liberal coalition, as the Democratic-primary polls suggest. Her political career began in a pre-Obama era, when Democrats were more nervous about offending conservative sensibilities than they are today. But Mr. Obama’s legacy rides on her, just as Mr. Reagan’s did on George H. W. Bush. If she wins, his policy victories are much more likely to be locked in and the Republican Party much more likely to make peace with them.

That’s the similarity. Two differences, though, aren’t helpful to Mr. Obama and Ms. Clinton.

The first is that Mr. Obama does not seem as intent on winning a third Democratic term for someone else as Mr. Reagan was on winning a third Republican one. Mr. Obama’s State of the Union address didn’t do much to tee up issues for Ms. Clinton to use in the campaign: Not even gun control, which we had been led to expect would be a big part of the speech, got much airtime.

Mr. Obama can get engaged in the race later this year, of course. But the second difference is not in his control.

Mr. Reagan was seen as a success by the general public, not just by people who shared his ideology. Mr. Obama isn’t seen that way. Much of his State of the Union address went against the grain of public opinion. According to the president, Obama-care is working well, the economy is booming even if it is also generating some anxiety, we are taking excellent care of our veterans, America is more respected than ever and the administration has a strategy that is reducing the threat of terrorism. According to the public, none of this is true.

Mr. Reagan’s approval rating rose during his final year in office, helping him get the successor he wanted. Maybe the same will happen for Mr. Obama. Ms. Clinton had better hope so — but she didn’t get much help from Mr. Obama’s speech.

Ramesh Ponnuru is a columnist for Bloomberg View.

First Published: January 17, 2016, 5:00 a.m.