When anyone asks what my father does, I say he’s a retired teacher. He did, after all, teach high school science and Latin, so I’m not lying. I’m just not telling the whole story: My father, married to my mother for 45 years, is a Catholic priest. Not a former priest, but a member of the clergy in good standing in the Roman Catholic Diocese of Bridgeport, Conn. Especially on a date, that’s a conversation stopper.

Despite his 100 percent Italian background, my dad grew up Methodist in Providence, R.I., in a family with anti-Catholic leanings. (His grandfather, from his perch outside his grocery store, used to refer to any passing priest as “the devil.”) In his mid-20s, seeking to deepen his faith, my father explored different churches. One Christmas Eve, he attended midnight services at an Episcopal church, the main United States branch of the Anglican Communion. It included ritual elements inherited from Roman Catholicism. He brought along his grandmother, whose stories about growing up in Italy always held special resonance for him. When the priest held aloft a statue of the baby Jesus, she got emotional, saying she was reminded of the Catholic chapel she had worshiped in as a child. My father believed he’d found his place.

My dad was ordained an Episcopal priest in 1970, the same year that he married my mother and began doctoral studies in theology at Oxford. But Catholicism always pulled at him. In Providence, he argued with the Episcopal bishop over the Assumption of Mary — the belief that Mary was assumed body and soul into heaven immediately upon death, part of Catholic dogma but not accepted by all Anglicans.

At Oxford, he devoured the writings of one of England’s most famous Catholic converts, Cardinal John Henry Newman. Even his children weren’t immune. My parents named me Mary Benedicta, a name that evokes images of a wimple-bedecked nun. (They gave my brother the middle name of “Becket” after Thomas Becket, venerated by both Catholics and Anglicans as a saint.) So when Pope John Paul II issued a pastoral provision in 1980 allowing qualified married Episcopal priests to convert to Catholicism and retain their ministry, my father applied. In 1984, after two years of preparation, he was one of the first priests ordained under this process in the United States.

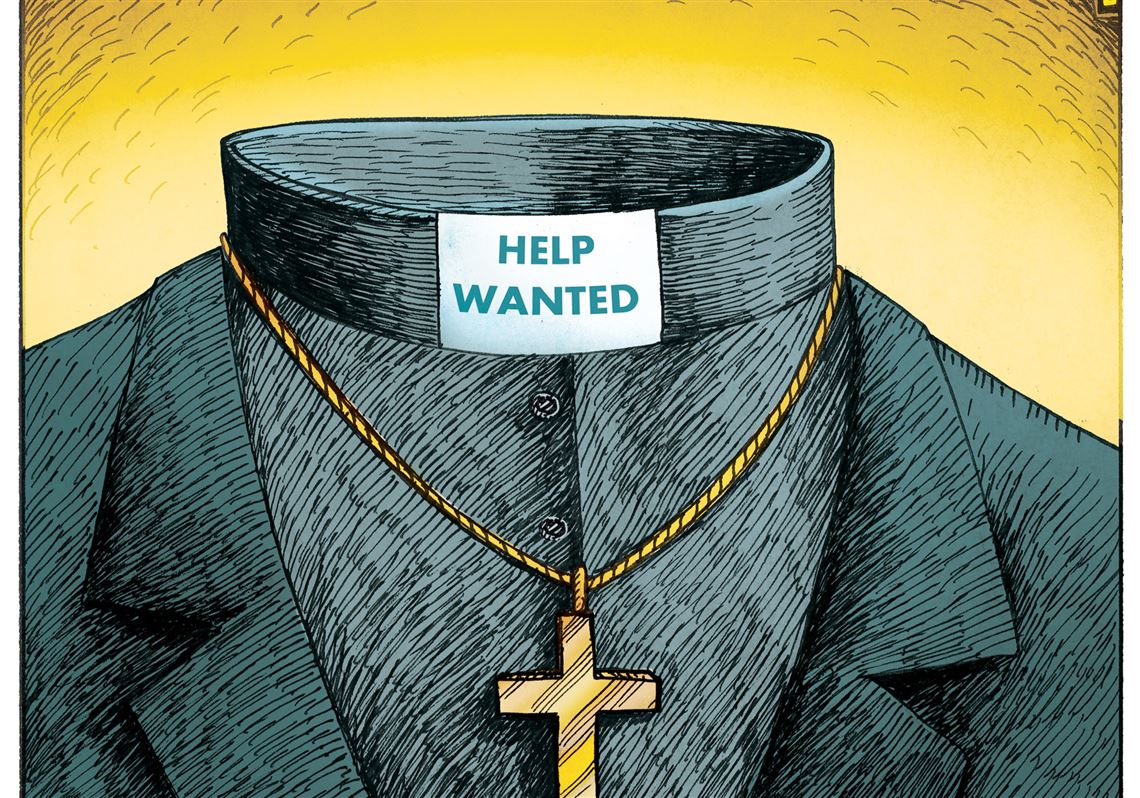

With Pope Francis visiting the United States this past week, priestly celibacy is up for discussion for the first time in decades. In February, in response to a question about married priests during a meeting with the Roman clergy, the pontiff stated that the issue was on his agenda. His secretary of state has reaffirmed that celibacy can be discussed because it’s a matter of church tradition, not core tenets.

Unlike dogma, tradition can evolve. Although the history of celibacy is complex, in Christianity’s early centuries some priests had wives, while monks, devoted to contemplative prayer, were celibate. A married man could be ordained a priest, but once ordained, a priest was forbidden to take a wife.

In the Middle Ages, the discipline of celibacy spread throughout the Western Church, in part to adhere to a reformed vision of the priesthood and in part to protect church property from being passed on to wives and children. It’s been enshrined in Canon Law since the promulgation of Pope Benedict XV’s 1917 code. Relaxing that rule would help reverse the shortage of priests, the kind of pragmatic solution to a pastoral problem that the pope gravitates to, as shown by the recent announcement of simplified rules for annulments.

Proponents of priestly celibacy rely on symbolic and practical arguments for maintaining the tradition. The priest represents the alter Christus, and is married to the church. On the practical side, a family takes up a lot of time and energy, and being a priest is a mission more than a job.

The faithful, however, have adapted to other evolutions of discipline and tradition — think eating meat on Fridays and Mass celebrated in the vernacular. The practical argument carries more weight for me. Sharing my father with so many people rankled when I was a child. Repeated refrains: “But it’s the weekend!” “But it’s Christmas!” My mother often struggled to find her place in communities with no precedent of priests’ wives.

Many jobs, though, are all-consuming, like those of doctors, police officers and other clergy. And more important, the church needs priests. In the United States, the number has declined by about a third since 1980, to 37,578 from 58,398, according to the Center for Applied Research in the Apostolate at Georgetown University. Globally, while the number of priests has been increasing in Asia and Africa, it has been declining in Europe and the Americas.

In concrete terms, almost one in four of the total number of parishes worldwide lacks a resident pastor. Clergy members often must divide their time among different churches, or handle an entire parish on their own. My father and a part-time priest, for example, serve about 2,000 families. That translates to roughly 10 minutes of dedicated time per family per month.

Would optional celibacy solve the priest deficit overnight? No. But it would certainly help. A great place to start: welcoming back to the priesthood the tens of thousands of men who left to marry. In a signal that Pope Francis might be considering such a scenario, when he celebrated the 50th anniversary of several priests in Vatican City earlier this year, five priests who had left their ministries to marry were in attendance. In another signal last November, the National Conference of Bishops of Brazil decided to study the possibility of ordaining married elders to shore up the priest shortage in underserved areas.

We need only look to the Catholic churches of the Eastern rite — which maintain their own liturgical and disciplinary heritage while in full communion with Rome — to see how it could work. Men may marry before being ordained, but not after, and bishops must remain celibate. We could also look at my father, one of about 100 Catholic priests who are married, and used to be Episcopal priests.

Would Catholics accept married priests? Most people in the five parishes my father has served over the past 30 years have welcomed him. And local church officials signaled their vote of confidence when they installed him as pastor of St. Mary’s in Norwalk, Conn., in May. Phyllis Smith, who is 90 and lives in Norwalk, liked my father as a priest in her New Canaan parish in the late 1980s in part because he was married, not in spite of it: “He was interested in families. I wish there were more married priests with his ideas — a lot of priests do not take the whole family into consideration.”

If the church did allow married priests, it would need to resolve serious practical concerns for priests with families, such as living arrangements, salary and health insurance and retirement benefits for spouses. When he was ordained, my father was told he’d need to keep a primary job in order to support his family. My parents paid for our house, and their teaching salaries were our main income. His role as a priest took second place, until he retired from teaching at age 73.

In part, that’s why he still believes priests should be celibate. “The priest stands at the altar as the icon of Jesus,” he told me. “He has to be free to offer himself up in sacrifice the way he offers the sacrifice of the Mass.” I respect his opinion, and respectfully hold my own: Not all married men should be priests, and not all priests should be married. But the option should exist. I suppose that’s part of the baggage of being a married priest — your children, like all children, sometimes disagree with you.

Benedicta Cipolla is a writer who has reported on the Vatican and American Catholicism. She wrote this for The New York Times.

First Published: September 27, 2015, 4:00 a.m.