Frederick “Fritz” Ostermueller pitched in the major leagues for 15 seasons, including stints with the Boston Red Sox, St. Louis Browns, Brooklyn Dodgers and Pittsburgh Pirates. In 1934, at the beginning of his career with the Red Sox, he faced Babe Ruth at Yankee Stadium. In 1947, near the end of his career with the Pirates, he pitched against Jackie Robinson during Robinson’s historic first big-league season.

Ostermueller’s first encounter with Robinson was one of the most dramatic moments in “42,” the movie about Robinson crossing baseball’s color line. In “42,”Ostermueller, portrayed as a young, hard-throwing right-hander, nearly causes a riot when he deliberately hits Robinson in the side of the head with a fastball during the final game of a three-game series in May 1947. In the ensuing shoving match, he repeatedly yells, “He doesn’t belong here.”

When “42” premiered at the start of the 2013 baseball season, critics praised its accuracy, but Ostermueller’s daughter, Sherrill Duesterhaus of Joplin, Mo., was shocked by the portrayal of her father as a raging, violent racist. She wrote to the Pirates organization and the baseball commissioner’s office for help clearing her father’s name. She also asked the film’s producers to apologize for what she believed was the maligning of her father’s character.

Ms. Duesterhaus soon received support from Sally O’Leary, editor of The Black and Gold, the official newsletter of the Pittsburgh Pirates Alumni Association, and from Hall of Fame sports writers Murray Chass and Bill Madden, who wrote that the pitch actually hit Jackie Robinson on the wrist and that Robinson during his entire career never was hit in the head. Other writers also noted numerous inaccuracies in the movie and attacked its portrayal of Ostermueller. An article in The Atlantic asked, “Hey, 42: Why All the Hate for the Pittsburgh Pirates?”

■ ■ ■

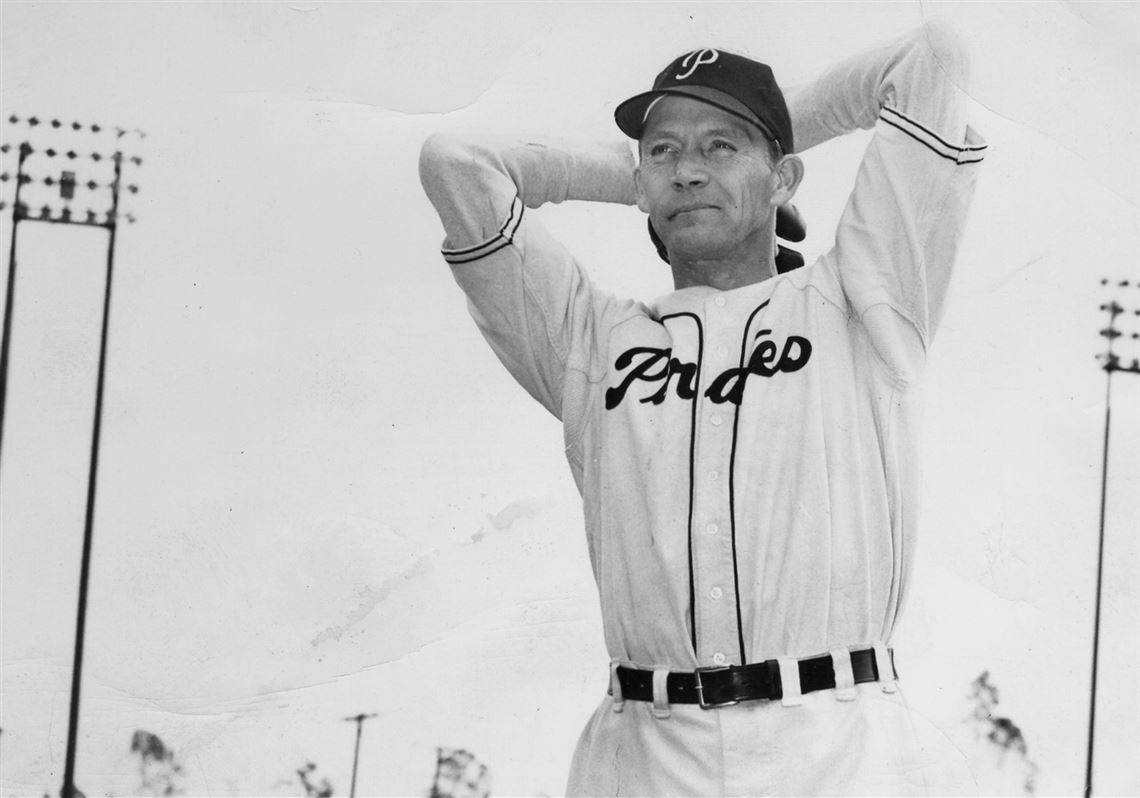

The real Ostermueller who faced Robinson was a 39-year-old left-hander nearing the end of an injury-plagued career. He’d suffered for years with sinus problems and headaches after being hit in the face by a line drive off the bat of Hank Greenberg, then playing with the Tigers. After another line drive off the bat of the White Sox’ Zeke Bonura struck him on his pitching elbow, he had surgery to have the elbow cap removed. To prevent his elbow from locking when he pitched, he had to develop an odd windmill windup to stretch out his arm before delivering the baseball.

In 1947, Ostermueller, affectionately known to his teammates and Pittsburgh sports writers as “Old Folks,” was relying more on guile than speed. His strategy included getting the respect of batters by pitching them inside and moving them off the plate. According to his daughter, Ostermueller told his wife the night before facing Robinson that he was worried about hitting him because he crowded the plate.

There’s no evidence that Ostermueller held any animosity toward Robinson, but he had said in a 1946 interview with Les Biederman of The Pittsburgh Press that he hated Branch Rickey. He blamed Rickey, then the St Louis Cardinals’ general manager, for keeping him in the team’s minor league system, at that time called Rickey’s “chain gang,” for the first eight years of his professional career.

Ostermueller came to Brooklyn in 1944, at about the same time Rickey became the Dodgers’ president. Rickey ordered him to the minor leagues just weeks before the pitcher became a “10-year man,” a designation that would have protected him from a minor-league assignment. When sports writers asked Rickey why he was sending the veteran down, he told them, “He’s not my type of ballplayer.” After Rickey’s action, a cartoon in the New York World-Telegram likened him to Simon Legree for selling the pitcher “down the river.”

Ostermueller filed a complaint with Baseball Commissioner Kenesaw Landis, but he ended up with the Pirates before Landis could reach a decision. From the moment Ostermueller put on a Pirates uniform, he became a Dodgers nemesis. In 1946, his late-season shutout of the Dodgers helped to derail their pennant chances. When the Dodgers made their first trip to Pittsburgh in 1947, he was determined as ever to beat them.

On May 15, 1947, Robinson made his major-league debut against the Pirates. Playing first base, Robinson went two for five, with a controversial bunt single. The Pirates’ 7-3 victory was highlighted by Ralph Kiner’s two home runs.

The next day, Robinson went two for four as the Dodgers bounced back against their former teammate, Kirby Higbe, and defeated the Pirates 3-1. After winning 17 games for the Dodgers in 1946, Higbe was traded to the Pirates after telling Rickey that he did not want to play with a black man.

On May 17, Ostermueller took the mound.

■ ■ ■

Wendell Smith, the sports editor of the Pittsburgh Courier, attended all three games. Because the Baseball Writers’ Association of America refused to grant Smith a membership card, he wasn’t allowed in the press box and had to watch from the stands.

Smith’s interest went far beyond reporting the games. He had recommended Robinson to Rickey. When the Dodgers executive signed Robinson to a contract, he hired Smith to be the rookie’s companion during spring training. So Smith was eager to see the reception Robinson would receive in Pittsburgh after being brutally taunted in Philadelphia by Phillies manager Ben Chapman.

Instead of offering game summaries, Smith recounted what he considered the two most racially charged moments in the series. The first occurred with Robinson’s bunt in the opening game. When Pirate pitcher Ed Bahr fielded the ball and threw it wildly to first base, Robinson collided with first baseman Hank Greenberg. Knocked to the ground, Robinson got his feet and raced to second on the wild throw.

Smith wrote that the “play was the type that prejudiced writers and players” and that “big-league owners used to say would cause a riot. ... In this particular instance, however, it was just the opposite.” Having endured anti-Semitic taunts throughout his career, Greenberg, baseball’s first great Jewish star, made sure that Robinson wasn’t hurt, then told him to fight back with his glove and bat. In his column, Harry Keck, sports editor of the Pittsburgh Sun-Telegraph, wrote that Greenberg told Robinson, “Stick in there. You’re doing fine. And keep your chin up.”

The other incident — the one misrepresented in “42” — occurred in the top of the first inning of the final game. After Ostermueller retired lead-off hitter Eddie Stanky, he faced Robinson. Ostermueller’s first pitch, according to Smith, “was fast, and if he hadn’t thrown up his arm, Jackie might have been beaned.” According to his account, the Dodgers, thinking the ball had struck Robinson in the head, shouted threats at Ostermueller until Robinson, hit in the arm but uninjured, “got up and walked to first base.”

Smith wrote that, after walking later in the game, the Pirates’ Frankie Gustine told Robinson, who was playing first base, that Ostermueller’s pitches jump in at right-handed hitters, “and that’s what happened in your case. I’m sure he didn’t mean it.” He added that Gustine asked Robinson “not to feel that anyone was trying to hurt him.... and told Robinson he was glad to see him in the majors.”

After the series was over, Smith praised Greenberg, Gustine and the Pirates for their treatment of Robinson. He added, “It may be that Pittsburghers admire him for the way he carries the tremendous load he has with ease and grace. Or it may be that it’s a club of high-class players who are too big to hit him below the belt because he happens to be of a different hue.”

United Press International carried a photo of Robinson doubled over at home plate, clutching his left arm, as the umpire signals him to take his base. The daily papers, however, barely mentioned the incident. Biederman noted Ostermuller’s remarkable performance in shutting out the Dodgers 4-0, while giving up 12 base hits, two walks and a hit batsman. In his notes on the game, he added, “Jackie Robinson collected a clean single to center and beat out a bunt to run his batting streak through 14 games in a row.... Osty threw a high pitch that caught Robinson on the left wrist in the first inning.”

Ostermueller faced Robinson and the Dodgers five more times that season. On June 5, he lost 3-0 at Ebbets Field as Robinson went three for four with a home run, and on June 24, he lost a 4-2 match to the Dodgers at Forbes Field, a game in which Robinson stole home for what turned out to be the winning run.

After lasting less than two innings in an 8-4 loss to the Dodgers on July 27, Ostermueller became a part of baseball history in a 16-3 victory at Ebbets Field on Aug. 26. After the Pirates knocked Hal Gregg out in the second inning of that game, the Dodgers brought in Dan Bankhead. He was the first African-American to pitch in a major-league game.

On Sept. 17, Ostermueller faced Robinson for the last time in the season in a 4-2 loss at Forbes Field. In the fourth inning, Robinson hit a home run that the makers of “42” turned into the movie’s dramatic climax. In the fictionalized account, an unrepentant Ostermueller dares Robinson to hit his best pitch. Robinson hits the pitch out of Forbes Field and trots around the bases in what’s portrayed as a game- and pennant-winning home run. In reality, there was no taunting, and the home run didn’t clinch the pennant. The Dodgers did that days later.

■ ■ ■

Ostermueller ended the 1947 season with 12 wins and 10 losses for the Pirates, whose 62-92 record put them in a tie for last place. The Dodgers, with Robinson winning the Sporting News Rookie of the Year Award, won the pennant with a 94-60 record, then lost the World Series to the Yankees. In his autobiography, “I Never Had It Made,” Robinson remembered the death threats, the taunting and the attempts to intimidate and injure him. But his only memory of Ostermueller was taking advantage of the pitcher’s slow and deliberate windup and stealing home with the winning run.

Ostermueller pitched one more year with the Pirates before retiring. He and his wife, Faye, and daughter, Sherrill, returned to their hometown of Quincy, Illinois, where Ostermueller became a broadcaster for the minor-league Quincy Gems before opening a motel. He died Dec. 17, 1957, barely a year after Robinson retired from baseball.

To this day, Ms. Duesterhaus hasn’t heard from the baseball commissioner’s office or the producers of “42.” Wouldn’t it be a good thing for baseball, still emerging from its steroid scandal, to clear the name of Ostermueller, who did no harm to Robinson or our national game, and for the makers of “42” to show the courage of a Robinson, whose heroics didn’t need exaggeration, by admitting they made a grievous mistake?

Richard “Pete” Peterson (peteball2@yahoo.com) grew up on the South Side. The former English professor at Southern Illinois University is the author of “Growing Up With Clemente” and “Pops: The Wille Stargell Story.”

First Published: August 3, 2014, 4:00 a.m.