For the past several Congresses, few practices have been so universally reviled as earmarks. Running for office eight years ago, the GOP made special projects and pork-barrel spending a focus of their ire, and during his 2011 State of the Union address, President Barack Obama promised to veto any bill to cross his desk with earmarks attached.

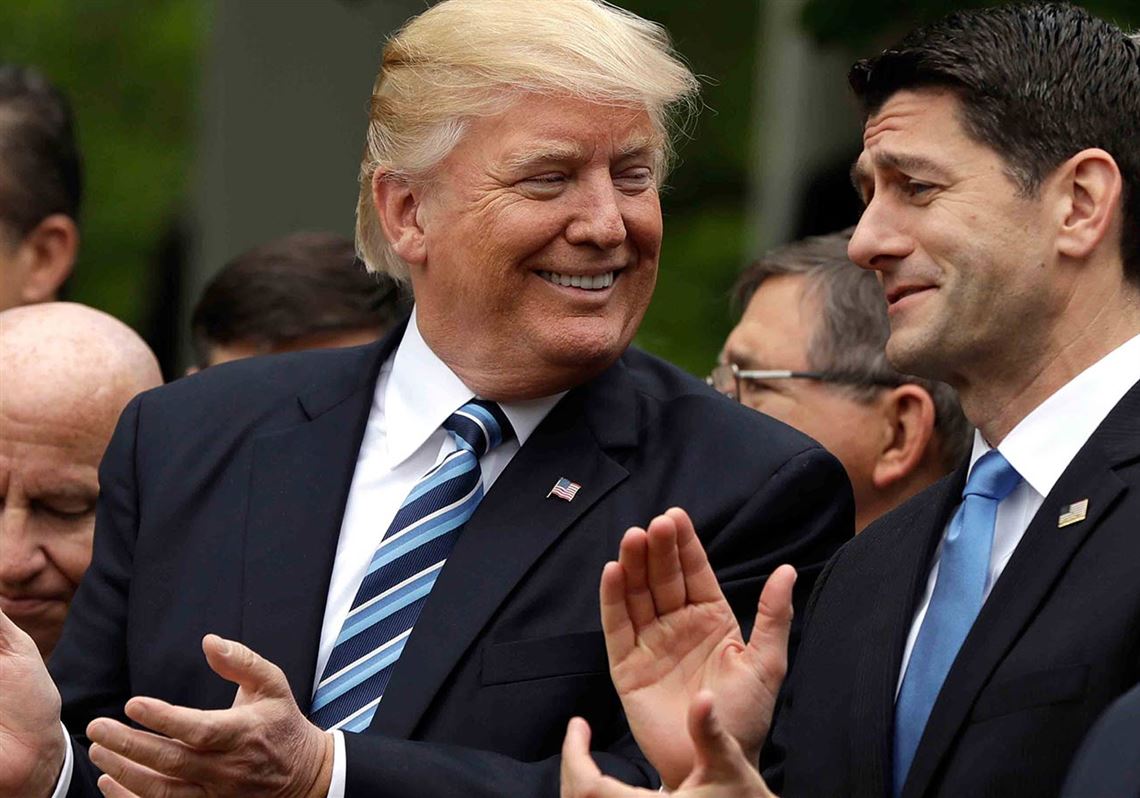

Since 2011, the ban has not been lifted and politics has only gotten more contentious. Which makes it an odd moment for House Speaker Paul Ryan and President Donald Trump to float the idea of reversing the earmark ban. Could bringing back earmarks make Congress more effective? A panel of constitutional scholars hosted by the American Enterprise Institute was hesitant to make promises, but wondered if the idea wasn’t worth trying.

“What do we have to lose? The current congressional process is broken,” said Jason Grumet, founder and president of the Bipartisan Policy Center.

For several sessions now, Congress has been marked by heating wranglings over policy, often leading to deadlocked votes, last-minute negotiations and the perpetual threat of a government shutdown over issues like the debt ceiling and the federal budget. Proponents of earmarks say the idea is not to buy votes, but to give members cover for making difficult votes in favor of the national, rather than local, interest.

“Earmarks were never drivers of federal spending overall, or of the federal deficit,” explained Frances Lee, a professor of political science at the University of Maryland. Instead, these projects allowed members to demonstrate to their districts that they were working hard in Washington and also meant that more members had a stake in a bill’s passage.

Although the tea party attacked earmarks as paragons of government waste, they never amounted to more than a tiny slice of government spending. When first tallied in 1992, they amounted to $2.7 billion of federal spending, rising to $29 billion in 2006.

Given the size of the federal government, such projects are barely a rounding error. This is a small price to pay to move Congress away from brinkmanship. In absence of earmarks, Ms. Lee says, politicians are driven to focus more on political posturing.

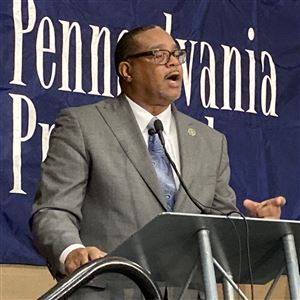

Jay Cost, a political scientist, writer and contributor to the Post-Gazette, has studied the American founding closely. He thinks pretending that politics is not about give and take is naive. “As long as there has been this sort of doe-eyed ideal that members of Congress act completely selflessly, there has been also a more hard-bitten acknowledgement that that’s not how things work.”

Mr. Grumet says earmark spending was a low-cost way to build camaraderie, something he likened to office snacks. Relatively cheap in the grand scope of things, they nevertheless are among the first things placed on the chopping block. “Every authentic human relationship is transactional,” he said. “The idea that members of Congress should somehow be different is this quaint notion that has no bearing on reality.”

In theory, earmarks are intended to ensure that different areas of the country or interest groups get their piece of the government pie. The concern is that this small-level corruption could balloon, creating interest groups that band together, rather than cancel each other out. “As a general principle, the politics of distribution lend itself to big corruption generally. This isn’t a hypothetical concern; it happened at several times over the course of the 19th century,” cautioned Mr. Cost.

Ironically, earmarks may not be as effective today as they were in the Obama administration. In the present Congress, where the GOP holds slim majorities and strong partisan opposition has left members unlikely to cross the aisle, internal party splits have greater weight. Right now, the Republican Party includes the Freedom Caucus, a group of members who claims it “can’t be bought.”

If this group of members comes to hold the balance of power by breaking with Republicans, earmarks would have minimal efficacy. The question is, does either party even want to try?

Erin Mundahl is a reporter for InsideSources.

First Published: March 23, 2018, 4:00 a.m.