Even as the federal government guaranteed uninterrupted Medicaid coverage during the COVID public health emergency, a growing number of children in Pennsylvania are living without health insurance.

Pennsylvania is one of only three states, alongside Connecticut and Wisconsin, that saw declines in insured children.

The findings come from the State of Children's Health report by Pennsylvania Partnerships for Children, bringing new momentum to their calls for continuous Medicaid enrollment for young kids.

The PPC analyzed 2022 Census data, digging into factors such as income level, race and ethnicity, poverty level and geographic location. The researchers found that the rate of uninsured Pennsylvania kids increased, from 4.4% to 5.2% between 2021 and 2022.

This isn’t a consequence of children losing Medicaid coverage since the disenrollment freeze expired this April. The COVID-era safety net, which allowed families to keep their coverage for three years without renewing, was still well in place.

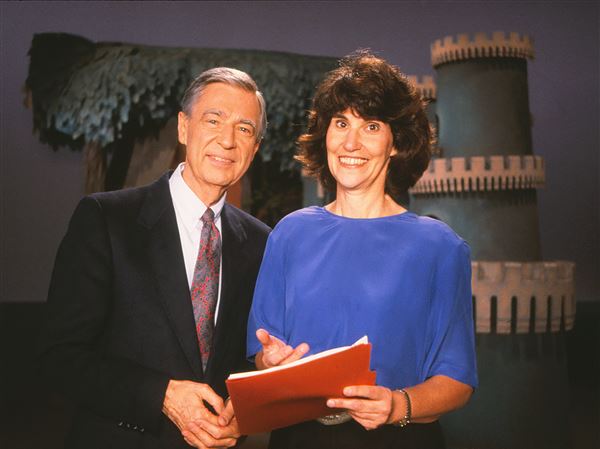

Becky Ludwick, vice president of public policy at Pennsylvania Partnerships for Children, says the continuous enrollment provision should have resulted in at least stable coverage in 2022. That wasn’t the case.

“That really caught us off guard,” Ms. Ludwick said. “This year, in 2023, with the Medicaid unwinding starting, the impact and the loss of coverage we're seeing isn't even reflected in these numbers yet. It's really troubling ahead of what we expect to be another year of loss of coverage for kids.”

Younger children were the most vulnerable. Uninsured rates rose significantly for children under age 6, from 4.6% in 2021 to 5.6% in 2022, and school age children, 4.4% in 2021 to 5% in 2022.

Lack of coverage or even short gaps can result in missed appointments and delayed care for chronic conditions such as asthma. This, in turn, can risk more emergency department visits and missed school days, the report writes.

Advocates say kids are feeling the consequences needlessly with several free and subsidized options available through Medicaid, CHIP and Pennie.

“Pennsylvania CHIP is actually, I would say, one of the leading states as far as eligibility goes,” Ms. Ludwick said. “We have a buying program where a family who earns over a certain income can still purchase CHIP for their children. They get the same comprehensive coverage but they just pay the full premium, which is still a very reasonable amount.”

But Ms. Ludwick says parents may not know that such options are available for their child or they may struggle with the application process. The report shows that 7% of children who are eligible for Medicaid insurance weren’t enrolled.

“Sometimes it's very difficult for families to navigate the process,” Ms. Ludwick said. “Those barriers have caused, unfortunately, a wall between families with children who are eligible for the program but yet to get those benefits. It takes a lot of time and effort to walk through an application process, not counting if there's missing information or if county assistance offices or the state needs more information from a family. It's not a very easy process.”

By race, Asian children and Hispanic or Latino children did see strides from 2021 to 2022. But the numbers moved in the opposite direction for American Indian and Alaska Native children, Black children, White children, and children of multiple races.

“For Black children in particular, we didn't find disproportionality compared to the population numbers, but we did see that their uninsurance rate has increased from 2021 to 2022,” Ms. Ludwick said. “It's now actually higher than pre-pandemic numbers.”

The statewide rates only tell part of the story in identifying the uninsured population. Seven counties have at least 5,000 or more uninsured children, including Allegheny County. Together, they account for nearly half of all the uninsured children in the commonwealth. The remaining 74,000 uninsured children are spread across the other 60 counties.

The good news is that Allegheny County’s insurance rate for children is higher than the statewide average, despite some disproportionality among Asian children, Black children and Hispanic or Latino children.

“The county has a lower uninsurance rate, which is great,” Ms. Ludwick said. “It also follows the trend that the younger kids under age six are still higher [insured] than school aged kids.”

When it comes to children who are uninsured but Medicaid eligible, the number falls a bit lower than what the organization saw statewide. Still, 5% of Allegheny County kids fall under that category.

“That still translates into almost 6,000 kids who don't have insurance,” Ms. Ludwick said. “They could be enrolled in Medicaid but they're not, again, whether the family isn't aware of it, or there's just been a lot of barriers to enrolling their child.”

The fallout after the freeze

Pausing disenrollments during the pandemic proved to make a meaningful impact on Medicaid enrollment. Child enrollment in Medicaid increased by 22%, peaking at over 1.4 million children, according to PPC.

With pre-pandemic operations now resuming, a DHS online tracker shows that over 75,000 individuals under age 21 have lost Medicaid so far. Over half of them are due to procedural reasons.

Kids who lose Medicaid insurance should transition to other coverage like CHIP, an affordable option open to all families regardless of income, Ms. Ludwick said. It took until October for advocates to get a fuller picture of the transition process, when DHS added information on CHIP referrals to its site.

While CHIP enrollment has grown over the past year, it still falls short of what advocates would expect to see, with only 1 out of 3 children shifting from Medicaid to CHIP.

DHS has said the numbers don’t include applications or case transfers in progress. The disparity could also be due, the department said, to CHIP eligibility going up to age 19, versus age 21 for Medicaid. A child could also become ineligible due to leaving the state or moving to private health insurance. Parents may also decide against CHIP due to the premium costs.

“We're actually seeing a pretty low number of kids who are no longer eligible for Medicaid, making their way over to CHIP,” Ms. Ludwick said. “And that's still an open ended item. There are issues that the state is still working through that we're trying to better understand.”

One of them lies in how Pennsylvania and 29 other states conducted automated renewals, also known as 'ex parte' renewals. In August, the federal government found states were erroneously kicking everyone in a household off its Medicaid rolls, including kids who enjoy a higher eligibility threshold, if one person no longer qualified.

The PPC has since called on the state to immediately restore Medicaid coverage for kids who unnecessarily lost it.

“To date, we have not gotten confirmation that they've all been reinstated,” Ms. Ludwick said. “It's now been months since the federal government had flagged that issue.”

To minimize disruptions seen during the unwinding process in the future, the organization has also asked the Pennsylvania Department of Human Services to consider multi-year continuous Medicaid eligibility for children from birth to kindergarten. This is a critical developmental period – the American Academy of Pediatrics, for example, recommends 13 health visits for kids under 6 years old.

The lessened administrative workload would benefit both families and the state, which is still working out the renewal complications under limited staff, Ms. Ludwick said.

“We've been really encouraged by their response, and they've been lately signaling support of that change,” she said. “We're excited to continue working with them to get a policy in place. Children who have that continuous connection to health insurance can get their wellness visits and medications they would need without any gaps in coverage. It’s a huge win as far as health outcomes for kids.”

First Published: December 1, 2023, 10:30 a.m.

Updated: December 2, 2023, 8:05 p.m.