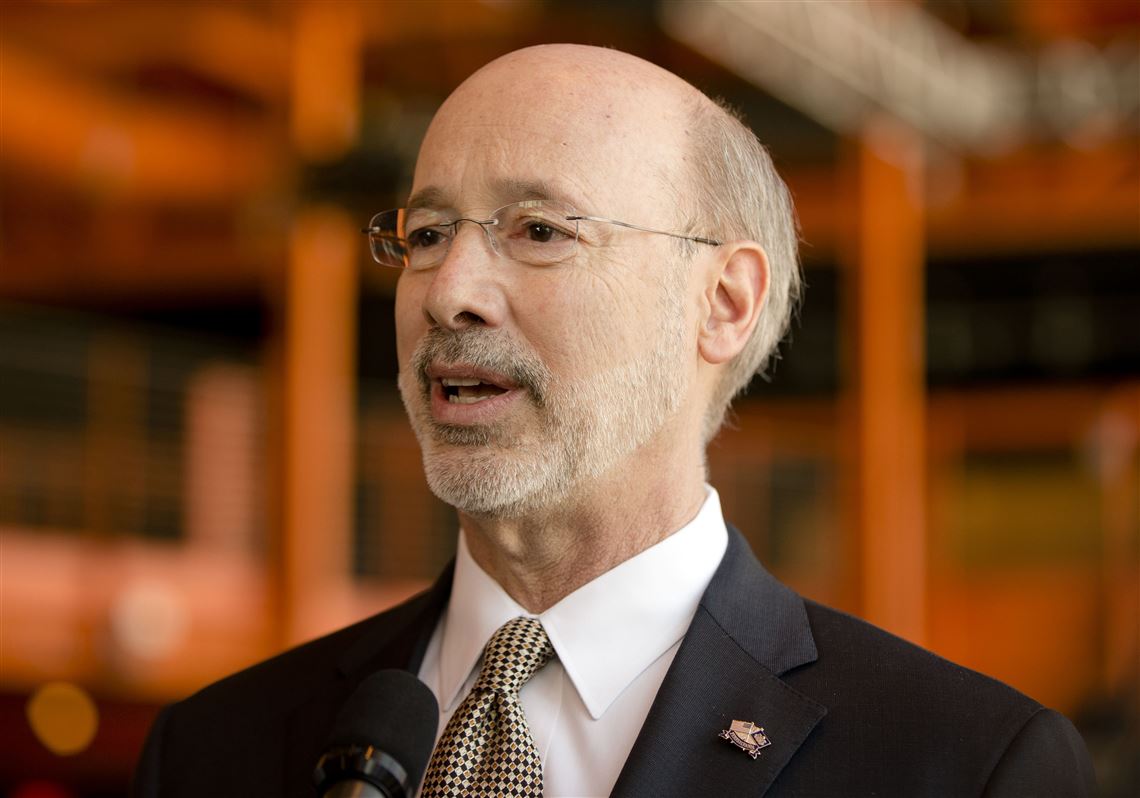

HARRISBURG — Health officials in Western Pennsylvania and families of people struggling with addiction cautiously embraced Gov. Tom Wolf's decision Wednesday to declare the opioid crisis a disaster emergency.

But many said they're still waiting for additional, more drastic changes to come.

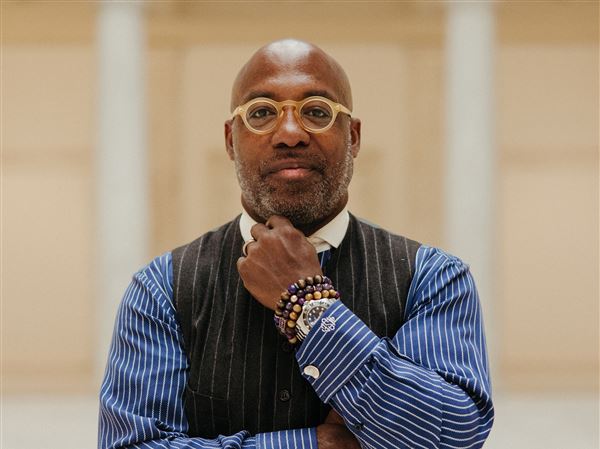

"How many times have we heard that we're going to put together a group, and this one is going to be different than the old one?" said Karl Williams, the Allegheny County medical examiner. "I'm getting very jaded by all of this."

The Democratic governor, at a press conference held Wednesday afternoon inside his reception room in the state Capitol, said the declaration is "not a silver bullet."

The declaration, signed before a crowd of reporters, allows the state to respond to the opioid epidemic as it would to a natural disaster or a severe storm, temporarily lifting regulations that it believes hamper its response efforts.

For example, emergency medical workers will now likely be able to leave naloxone, a drug administered in overdose cases, behind with people who are reluctant to immediately get further treatment. It could also reduce paperwork required when inspecting some high-performing drug treatment centers, in theory freeing up workers to focus on patients.

The declaration remains in effect for 90 days, though Wolf left open the possibility that he could sign another one at the end of that period.

The administration hopes to learn during those three months how lifting regulations could help or hinder its treatment efforts. If it feels it has been successful, it could begin the longer process of lifting some of those regulations permanently.

The declaration does not allow state officials to create new regulations (which would require public input) or to create new laws (which would require approval from the Republican-controlled House and Senate).

"It is imperative that we use every tool to try to contain and eradicate this public health crisis," the governor said. "The numbers...are staggering. The impact is devastating. We cannot allow it to continue."

Pennsylvania has the fourth-highest rate of drug overdose deaths in the country, according to the latest statistics available. State officials expect there were 5,260 drug-related deaths in the state last year, though numbers are still being finalized as medical examiners and coroners continue to receive drug test results.

What it does

Pennsylvania is the eighth state to declare an emergency because of the opioid crisis. The impacts of that declaration have varied from state to state.

In addition to allowing medics to leave behind naloxone, the Wolf administration has said it believes the declaration permits the following:

- Creates an Opioid Operational Command Center within the Pennsylvania Emergency Management Agency

- Allows patients to get admitted to narcotic treatment programs without first meeting face-to-face with physicians

- Makes overdoses and the births of children in withdrawal — or neonatal abstinence syndrome — reportable to the Department of Health

- Expands access within state government to data from the Prescription Drug Monitoring Program — a registry of medications received by patients since 2016

- Tightens regulation of fentanyl derivatives to match federal standards

- Decreases the number of times the state must do licensing reviews for high-performing treatment centers

- Lets pharmacists partner with other organizations to increase access to naloxone

- Waives separate licensing requirements for hospitals in order to expand access to drug and alcohol treatment

- Eases the distribution of medication-assisted treatment like Suboxone at facilities' satellite locations

- Waives fees for birth certificates for people with drug use disorders, so they can get treatment.

Western Pennsylvania reacts

A state declaration of emergency to cut some of the red tape that bedevils the response to opioids could only help, but isn’t likely to halt the march of record-shattering overdoses, experts and advocates said as details emerged Wednesday.

"The opioid crisis is so vast and so deep that it's going to take extensive measures in many different domains to address it,” said Neil Capretto, medical director for Gateway Rehab. The declaration “will not solve the problem but it's a step in the right direction that will, to some degree, improve the problem."

"It sounds to me like they have given some thought to the real barriers to being able to make quick change and to react" to rising overdoses, said Jan Pringle, a professor in Pitt’s School of Pharmacy and director of OverdoseFreePA, a project that collects and analyzes drug death data.

One of the declaration’s most tangible, immediate effects will be to allow medics to leave behind the opioid reversal drug naloxone when they respond to an overdose. That way, a family member or friend can save them if they overdose again.

Experts seconded Mr. Wolf’s call for wide distribution of naloxone, rejecting perceptions that increased availability of the life-saving drug may enable narcotic users to continue their habits, confident that they will be saved.

"It has not been our experience that the use of naloxone is something that is particularly pleasant. It wakes someone up from an overdose and immediately puts them into a withdrawal situation," said Karen Hacker, director of the Allegheny County Health Department. "Our job has got to be to save as many lives as possible," she said, and anything that keeps people alive and smooths the path to treatment is welcome.

Officials and advocates also hope the declaration will allow state agencies to more swiftly and more widely share information about drug overdoses among themselves. The administration plans to begin a Command Center that will require officials who are already meeting about the epidemic to meet more frequently.

Dr. Pringle applauded the governor’s move to centralize the response to the epidemic, so that information can flow more readily between the various state agencies and numerous researchers and practitioners trying to take on the opioid epidemic. She said that until recently, researchers have seemed to be in “silos,” with no ready means to share their findings.

The declaration will allow the Department of Health to make overdoses and neonatal abstinence syndrome conditions that must be reported to the state when people survive them, according to its acting secretary, Rachel Levine. Currently, much of the data on those conditions comes from incidents in which the patient dies.

If the declaration allows the free flow of medical data, it could help researchers come up with plans to control the epidemic, said Donald S. Burke, dean of the University of Pittsburgh's Graduate School of Public Health.

“There's currently substantial data on the opioid epidemic that is either hidden or lazy, meaning not being used,” he said. “We could turn that into active data. This would be one of the least expensive ways to get the most bang for the buck."

Members of families that have been affected by opioids immediately asked whether the declaration would expand the depth of drug treatment.

"We would like to see at least a six-month [rehab] program started" and covered by insurance, in contrast to the three-or-four-week inpatient stays and scattershot follow-up that is now the norm, said Jeanna Fisher, of Whitehall, who in April lost her 28-year-old daughter Marley Fisher to an overdose. Ms. Fisher now runs the advocacy group Pittsburgh Won't Forget U, which has crafted a 26-point plan for addressing the crisis.

"Sometimes it's six months to a year [of treatment] to actually give the addict a chance,” she said.

"You can't put somebody through treatment for 21 days, 28 days max and them boom, back out on the streets, and say, ‘OK, have at it,’" agreed Domenic Marks, of Ross, a member of the family support group Bridge to Hope. He added that there should be more emphasis on preventing drug abuse in the first place. "We need to educate, really quickly, families, people who are getting to that age bracket that are starting with using."

Rehabilitation, treatment, medication assisted therapy and cognitive therapy all need to be coordinated, said Dr. Williams, the Allegheny County medical examiner, adding that those approaches are “all the stuff that is expensive and not covered because we direct all of our money toward big pharma and drugs”

Dr. Williams, in a statement released Thursday, called the emergency measures "a valuable, necessary and welcome contribution," that "provides numerous specific cures for some of the regulatory problems that hinder immediate local efforts."

“What is most frustrating to me, as both a physician and citizen, is that without a full-out effort by both the federal government and the insurance industry, the steady flow of deceased individuals will continue," he continued. "Many of these individuals have committed to prior rehabilitation efforts, but due to the inadequate amount of time covered by insurance, find themselves a victim of their addiction. This is particularly evident in some of our local communities."

His office has so far finalized 594 fatal overdoses in 2017, but is still awaiting the toxicology reports from many possible drug deaths before producing a final number.

When someone needs treatment, they should be able to go to an accessible location, tap into a centralized resource, and find the right program, quickly, he said. "I'd like to try to turn Carrick into a test case for it," he said, referring to the city neighborhood that has seen the highest number of overdoses. Carrick was the focus of Riding OD Road and Life and Death on Santron Avenue, a special report in the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette.

Philadelphia officials believe that their city saw around 1,200 overdoses last year, according to a release today from Mayor Jim Kenney. He said the governor's "announcement makes clear that this epidemic threatens the Commonwealth as much as any natural disaster."

The declaration should have done much more to improve access to clean needles, so that intravenous drug users wouldn't be as likely to contract HIV or AIDS, said Alice Bell, overdose prevention project coordinator for Prevention Point Pittsburgh, which distributes syringes and naloxone.

"We're heartened that Governor Wolf would draw on his authority to declare a disaster emergency, but Prevention Point feels like the measures that are being discussed don't even begin to touch what's necessary to mount an effective public health response," she said. "We need a lot more."

State law includes needles in the list of items that can be considered drug paraphernalia, and therefore prohibited by law. Some in state government have said that change would require legislative approval.

Needle exchange is currently legal only in Allegheny and Philadelphia counties.

President Donald Trump in October called opioid abuse a national public health emergency, but did not immediately free up new funds.

"There's been a lot of lip service from the Trump administration, but they have yet to declare it a national emergency and put the dollars needed behind it,” said Dr. Capretto. "If we had a serial killer or an infectious disease killing one tenth of that number of people, we'd demand an appropriate response immediately."

Declarations "will help some, but addiction is a chronic disease, but still our healthcare system treats it like the flu or a sprained ankle,” said Dr. Capretto.

This story has been updated with additional quotes from medical examiner Dr. Karl Williams.

Rich Lord: rlord@post-gazette.com or 412-263-1542. Liz Navratil: lnavratil@post-gazette.com, 717-787-2141.

First Published: January 10, 2018, 7:06 p.m.