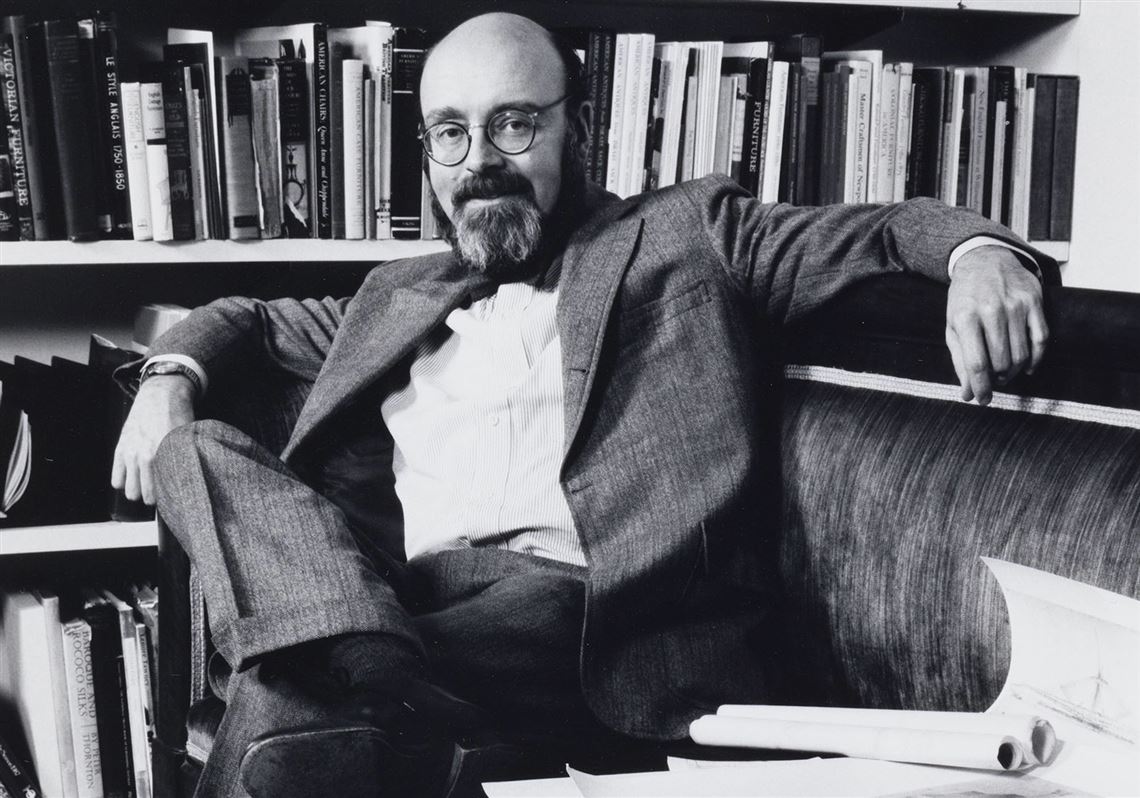

Christopher Pruyn Monkhouse, founding curator of the Heinz Architectural Galleries at Carnegie Museum of Art, died Jan. 12 from a stroke at Gosnell Memorial Hospice House in Scarborough, Maine. He was 73.

A visionary scholar and an ebullient, tea-drinking storyteller, Mr. Monkhouse enjoyed an international reputation. His roving curiosity ranged from architectural drawings to the poetry of Henry Wadsworth Longfellow to old English houses, Irish decorative arts and contemporary art.

While in Pittsburgh from 1991 to 1995, he acquired more than 6,000 drawings and some models of American, English and European architecture for the Heinz Architectural Center. When he arrived, a half-dozen drawings made up the collection, including several donated by modernist architect Richard Neutra. Later, the museum acquired a Frank Lloyd Wright drawing of a bridge for Pittsburgh’s Point and a drawing by Henry Hobson Richardson, architect of the landmark Allegheny County Courthouse.

A native of Portland, Maine, Mr. Monkhouse was recruited by Phillip M. Johnston, then director of Carnegie Museum of Art. Drue Heinz, the widow of Henry John Heinz II, endowed the Heinz Architectural Center with a $10 million gift in memory of her husband after he died in 1987. The couple shared a passion for architecture and restoring homes.

“We had a plum attraction. How often does a person get asked to lead a new effort with some significant resources?” Mr. Johnston said in a telephone interview.

Starting an architectural drawings department in the 1990s was unusual, Mr. Johnston said, recalling that only a San Francisco museum and the Museum of Modern Art in New York City had curators devoted to that pursuit. He doubted that Mr. Monkhouse would leave his job in Providence, R.I.

“I had known Christopher since the mid-’70s. He was the curator of decorative arts at the Museum of the Rhode Island School of Design. I knew about his architecture shows at RISD. I knew about his collecting of architecture. He was known for his strengths in working with donors, in making acquisitions by purchase or gift. He had an incredible visual memory. His scholarship was undeniable,” Mr. Johnston recalled.

When Mr. Monkhouse said he would consider coming to Pittsburgh, “I nearly dropped the phone. And I was thrilled,” Mr. Johnston added.

Mr. Monkhouse’s Ben Avon home was a museum, its walls covered by framed architectural drawings, said Patricia Lowry, retired art and architecture critic for the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette and The Pittsburgh Press.

As a boy, Mr. Monkhouse began collecting art, antiques, books and ephemera, plus superb American and British architectural drawings. As a curator, he wrote many scholarly articles for books and exhibition catalogs. He also lectured in America, England and Ireland.

Starting in 1992, Dennis McFadden, of Sugar Hill, N.H., worked with Mr. Monkhouse here as assistant curator and succeeded him.

“The Heinz Center really was created very much around his vision and the vision of Drue Heinz. He really understood what her aspirations for it were and was able to bring it to fruition,” Mr. McFadden said.

Mr. Monkhouse “addressed the extraordinary architectural heritage of Pittsburgh” and gave it “a larger international context,” Mr. McFadden said.

After the galleries opened in 1993, Mr. Monkhouse did a memorable show inspired by the work of Renzo Piano, setting up long tables with computers in the galleries.

“The use of the computers was to allow you to interpret the designs and understand Piano’s design methodology,” Mr. McFadden said, adding that while computer-assisted design in architecture began in the 1970s, “computer technology was really new to many architects when this show was exhibited.”

Another big hit was “Lord Burlington and the Ideal Villa,” about architect Andrea Palladio’s impact on 18th-century English architecture. The show traveled to London and Montreal.

“We had drawings at the Heinz Center that were extraordinarily important and valuable. In the Heinz Center itself, we linked it with an exhibition of drawings that related to Thomas Jefferson’s work in Virginia, where one most clearly sees the manifestations of Palladio’s ideas,” Mr. McFadden said.

In 1995, Mr. Monkhouse left Pittsburgh to work at the Minneapolis Institute of Arts, becoming the James Ford Bell Curator in the department of architecture, design, decorative arts, craft and sculpture.

In 2007, he became Eloise W. Martin Curator and chair of the department of European decorative arts at the Art Institute of Chicago. There, he organized an acclaimed 2015 show, “Ireland: Crossroads of Art and Design, 1690-1840.” He retired in 2017.

The son of William A. Monkhouse, a doctor, and Agnes Pruyn Linder Monkhouse, he was born in Portland, Maine, on April 2, 1947. After graduating from Deerfield Academy in 1965, where he curated his first art show, he studied English country houses at Attingham Summer School in Shropshire, England.

A Phi Beta Kappa graduate of the University of Pennsylvania in 1969, he earned his master’s degree in art history at the prestigious Courtauld Institute of Art in London, where he studied with Sir Nikolaus Pevsner.

After working at the Victoria and Albert Museum in London, he returned to New England as curator of European and American decorative arts at the Museum of Art, Rhode Island School of Design from 1976 to 1991.

He maintained a Maine summer home in Machiasport, an 18th-century Colonial house where you had to use a pump to get water in the kitchen sink. He settled in Brunswick when he retired in 2017.

He was predeceased by his father and mother; his aunt and stepmother, Marjorie Putnam Linder Monkhouse; and his brothers, William A. Monkhouse Jr. and Frederick L. Monkhouse.

Burial in Portland’s Evergreen Cemetery will be private. A celebration of his life will be held this summer in Brunswick at a time to be determined. In lieu of flowers, contributions may be made to the Bowdoin College Museum of Art, 9400 College Station, Brunswick, ME 04011.

Marylynne Pitz at mpitz@post-gazette.com or on Twitter:@mpitzpg

First Published: January 25, 2021, 10:45 a.m.