Alpha-gal syndrome, a rare allergy, is full of unsettling surprises.

It can render a single bite of hamburger life threatening.

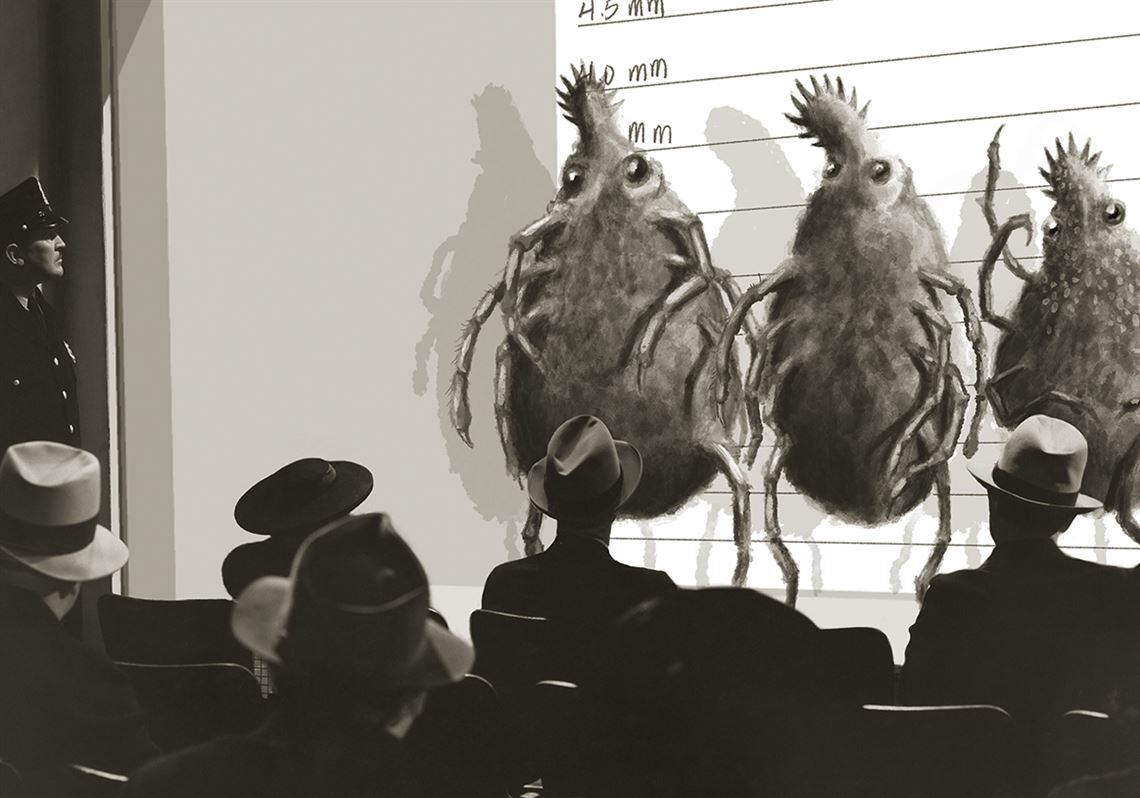

It isn’t the result of pulling a short genetic straw, but is most commonly acquired through a bite from the lone star tick, which is present in Allegheny County.

And AGS could have had everything to do with why Martha Stewart sold her 3,928 shares of ImClone Systems, Inc., stock in December 2001, which led to her five months in prison, five months of house arrest and two years of probation.

Before understanding how hamburgers, ticks and Martha Stewart may have all (figuratively) walked into a bar (lab?), the seriousness of this reaction should be appreciated, as was made clear by a late-July publication from the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

That report drew attention to AGS in general — as more than 34,000 suspected cases were identified from 2010 through 2018, compared to just 24 total in 2009 — but it mostly shined a light on the medical community’s AGS knowledge gap.

“For most clinicians, I’d say the CDC put it more at the fronts of our minds, or hopefully it will trigger us, when someone has an allergy we can’t understand,” said Brian Lamb, internist at Allegheny Health Network. “It’s very specific blood testing you have to do to find it. We really have to expand our thinking to include that in our tests.”

The CDC’s researchers asked 1,500 family practitioners, general practitioners, internists, pediatricians, nurse practitioners and physician assistants — those most likely to initially encounter a patient with AGS-like complaints — what they knew about this “emerging” syndrome.

The study concluded that 42% were not aware of AGS and, of those who knew about it, 35% were not confident in their ability to diagnose or manage it.

That might be rattling, especially for those already battling AGS, but there’s a good reason for medical providers’ lack of certainty: Community clinicians, and even those on the cutting edge of AGS research, are still figuring it out.

“Part of the problem is even identifying it,” said Lamb. “Unfortunately, it’s an allergic reaction, and everyone has different levels of allergic reactions. Some people may not even know they’re having one, and they may not be able to trace it back to eating red meat since most people don’t eat only red meat for a meal.”

Here’s what the medical community knows for sure.

“Alpha-gal” refers to galactose-alpha-1,3-galactose, which is a sugar found in all mammals except primates, a grouping that includes humans.

Because the sugar isn’t native to humans’ bodies, it can be seen as an invader. In those with AGS, the body “overreacts” to the presence of that sugar in mammal-derived foods and dumps a treasure trove of immune-related chemicals, resulting in a wide variety of symptoms.

That may sound exactly like a traditional allergic response, but these have some unique characteristics.

First, proteins are the cause of most allergic reactions. It’s entirely unusual for alpha-gal, a sugar, to trigger this kind of response.

And, apparently, AGS has nothing but time.

Waiting game

According to the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology, an anaphylactic reaction — one that is life threatening — typically starts within five to 30 minutes after coming in contact with an allergen.

Lori, an educator from the North Hills with AGS, tells a different story.

“If I have a microscopic spec of mammal unknowingly, by accident, then six hours later, to the moment practically, I start feeling nauseous,” said Lori, who prefers to be identified by her first name only. “I feel hot. My face turns beet red. And then it just increases from there to extreme gastrointestinal pain and vomiting.”

Lori calls herself “very reactive” to mammalian sources, and carries a double Epi-Pen with her at all times, since these — and any — allergic reactions can become life-threatening without warning.

By necessity, she avoids all red meat and dairy. Inhaling the fumes created by cooking red meat are even enough to generate symptoms for her.

When she needs medication, she uses compounding pharmacies so special formulations can dodge mammal-containing ingredients like gelatin. And to stay safe, she’s been known to call food producers to ask about the details of their ingredients, since even benign-sounding ones, like “filtered water,” can be created through a mammal-derived product called bone char.

But that’s just Lori. Others with AGS have life-threatening swelling. Some can eat dairy without issue. Some can eat most dairy but not ice cream, which inexplicably seems to cause more issues than other milk-based foods.

Recognizing the true breadth of reactions is a fairly new discovery, according to internationally recognized AGS authority Dr. Scott Commins, a University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill allergist.

“Affected individuals can have GI symptoms only — abdominal cramping, pain, diarrhea, vomiting — and no evidence of itching, hives, shortness of breath, etc.,” he told the Post-Gazette via email.

Though the symptoms are highly variable, their timing is a telltale sign of AGS, beginning two-to-six hours after exposure, which is well after typical allergic responses.

There are two potential reasons for this, explained Dr. Commins, who discussed the topic on a 2017 episode of “The Chair’s Corner,” the UNC department of medicine’s podcast.

First, blame the sugar. He theorizes that reactions to sugar’s triggers may take longer to develop, but with so few of those examples, it’s hard to know.

A more likely cause relates to fat, which is ever-present in mammal-derived foods, and how it is absorbed.

“We’ve done some challenges where we bring our patient volunteers in and feed them sausage. When we do that, we can find that the appearance of alpha-gal in the bloodstream is actually delayed three or four hours,” he explained. “So, there’s something about the processing of meat, and we think fat makes a good candidate to explain the delay.”

‘It’s (not) a good thing’

It doesn’t seem that anyone affected by AGS was born with it.

OK, so they acquired it. But how?

Back to Martha.

The “urban legend,” as described by Dr. Commins, involves a cancer medication linked to the company she’d invested in. That drug was produced in mice, which, as mammals, possess alpha-gal. While in their bodies, they unintentionally “decorated” the drug with those sugars.

When the drug was tested in patients, nearly a quarter of them developed anaphylactic-like reactions.

As the story goes, when the company moved toward alerting the FDA, Martha Stewart’s stockbroker heard about it, knew the stock would plummet, and gave her a heads up.

Because she sold her stock as a result, she ended up in legal trouble, and accidentally found herself in the middle of AGS’ discovery.

“Essentially the way the story goes is these patients were reacting because they had developed an allergic response to alpha-gal,” Dr. Commins explained on “The Chair’s Corner.”

A University of Virginia lab, led by Thomas Platts-Mills, helped identify how many patients were reacting to that would-be cancer drug. He went on to study the phenomenon further, in part with his allergy and immunology fellow, Dr. Commins.

When they began seeing patients who complained of allergic-like responses to red meat, they thought to run the alpha-gal test developed in response to the cancer drug snafu, and that “opened the Pandora’s box” of understanding AGS as a distinct set of reactions.

None of that explains how people developed that sensitivity, however.

They knew the reactions were delayed and focused in the southeastern U.S. When they looked at a map of where tick-borne disease Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever is concentrated, also in the southeast, they thought ticks — specifically that area’s predominant type, the lone star tick — might be the culprit.

And, as a certain kind of luck would have it, someone in their lab developed alpha-gal, just after receiving several tick bites.

Tick-related, not tick-borne

It’s now believed that AGS comes from a variety of ticks, not just the lone star variety, as evinced by the syndrome’s presence in areas of the world where lone star ticks are not.

But don’t call it “tick-borne.”

“It’s not like you’re going to get a rash,” like Lyme disease can cause. “It’s not like you’re going to have any sort of symptoms. It could be months later that you develop this allergy because allergies take a while to develop in the immune system,” Lamb said. “It’s not this immediate, ‘I was bitten by a tick, and now I can’t eat a hamburger.’”

It’s also not “tick-borne” because new research explains the issue is a component of the ticks’ saliva, not a substance acquired from other animals.

“It’s been shown more recently that ticks carry an enzyme that appears to create an alpha-gal sugar, or something very close,” Dr. Commins said. “So, they don’t need to feed first — the very earliest stages [of a tick] can bite, and create a risk for AGS,” but why certain tick bites result in AGS and others do not is still not understood.

Commins currently sees eight to 10 newly affected patients each week, but those numbers might reflect his AGS guru status.

Because so few clinicians are experts in AGS, or even feel confident enough to treat it, a robust social media community has formed of potential or already-diagnosed patients whose personal experiences serve as the most specific medical support some of them can find.

In the Pittsburgh region, for instance, there seem to be only a handful of self-identified affected individuals among those communities, which highlights an important takeaway despite the CDC’s alarm bells: The risk of AGS is still relatively low.

“We don’t want people thinking this is some wildly spreading epidemic or anything like that,” Lamb said. “Chances are you aren’t going to develop it even if you’re bitten by a tick. It’s just something for clinicians to keep in the backs their minds when something seems strange.

“We don’t want people to be terrified that they’re going to be bitten by a tick and never be able to eat a steak or a hamburger again. We don’t want people to panic about it.”

Abby Mackey is a registered nurse, and can be reached at amackey@post-gazette.com and IG @abbymackeywrites.

First Published: August 27, 2023, 9:30 a.m.

Updated: August 28, 2023, 9:57 p.m.