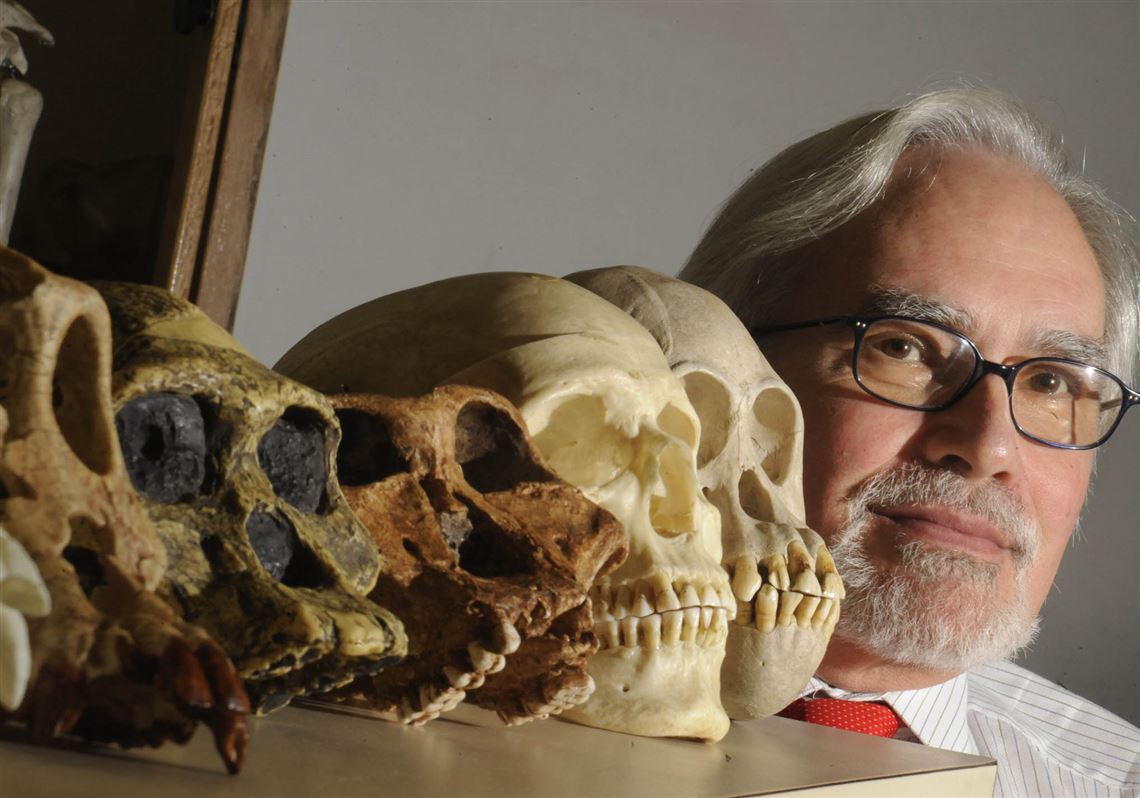

There goes Jeffrey H. Schwartz again, causing controversy in anthropological circles.

The University of Pittsburgh anthropologist — who drew criticism six years ago by saying we are more closely related to orangutans than to chimpanzees — hopes to shake up anthropology once again with a bold contention that the genus Homo, topped by Homo sapiens, should not only be redefined, but also split up into different genera.

His latest controversy was launched Thursday with publication of his and Ian Tattersall’s report in Science, “Defining the genus Homo: Early hominin species were as diverse as other mammals.” Mr. Tattersall is curator emeritus in the division of anthropology at the American Museum of Natural History in New York.

The article says that “we may find that human evolution rivaled that of other mammals in its evolutionary experimentation and luxuriant diversity,” as opposed to placing most human species from 2.8 million years ago to the present inside the genus Homo. Most species died off, leaving our species, Homo sapiens, as the sole survivor.

A genus is classification of related species, each of which are characterized by unique features specific to its members. Although there are no hard and fast rules for defining a genus, “most evolutionary biologists consider it a meaningful, natural grouping, based on structural and sometimes behavioral similarities between related species,” said Mr. Schwartz, who holds a Ph.D. in physical anthropology. As a rule of thumb, he said, the genus name is applied to a grouping of related species.

In terms of the genus Homo, and the species that have been put into it, he said, “the boundaries of both the species and the genus remain as fuzzy as ever, new fossils having been haphazardly assigned to species of Homo, with minimal attention to morphology, or the form and structure of each of the fossils.”

Mr. Schwartz argues that human fossils rarely undergo full analysis, and simply are placed in the long list of human species that have been assumed to be members of Homo. He points to Louis Leakey’s 1960 discovery of the 1.8 million-year-old fossils in Tanzania’s Olduvai Gorge as exemplary of the practice of automatically assigning fossils to the genus Homo.

However, he said, there “is scant morphological justification for including any of this very ancient material in Homo.”

“Indeed, the main motivation appears to have been Leakey’s desire to identify this hominid, known as Homo habilis, as the maker of the simple stone tools found in the lower layers of the gorge,” that Leakey claimed was the earliest species of the lineage leading to modern humans.

So debate continues over whether H. habilis was our direct ancestor, a dead-end branch of hominid, or a completely unrelated species.

Such designation of fossils in the genus Homo, when their age and appearance dictates otherwise, “so broadened the morphology of the genus that other hominids from other sites could be shoe-horned into it almost without regard to their physical appearance. As a result, the largely unexamined definition of Homo became even murkier.”

Detailed comparative study of fossils leading to a more realist grouping of them into species, and then those species into genera, he said, is necessary to better understand the evolutionary path to modern humans.

His preference, Mr. Schwartz said, would be to include Neanderthals, which are recognized as the species neanderthalensis, and fossil relatives into their own genus, and fossil specimens regarded as heidelbergensis and that species’ fossil relatives in a different genus. That would leave the genus Homo for our species, Homo sapiens, and our closest relatives.

“A big problem is that human paleontologists don’t look at the details of teeth and skulls, or the rest of the skeleton of fossil humans the way those of us who were trained broadly in the study of other mammals do,” he said.

As a result, “we are denying humans an evolutionary past of diversity that we see in any other animal. To try to treat human fossils as paleontologists do the fossils of other animals, we must start from scratch in analyzing them instead of trying to cram them into the species that are currently crammed into the genus Homo.”

Chris Stringer, an anthropologist at the Natural History Museum in England, said the Science article raises “important issues about the diagnosis of our own genus Homo, and which species should rightly be placed in it,” while agreeing that fossil traits should be at the center of any definition of early human.

“Recent research is placing more and more specimens from before 2 million years into the genus Homo, but as some of the material is quite fragmentary (for example the isolated jawbones), it remains unclear how ’human’ these individuals would have been throughout their bodies in their overall biology,” Mr. Stringer said.

David Templeton: dtempleton@post-gazette.com or 412-263-1578.

First Published: September 1, 2015, 4:00 a.m.