Tamara Allen-Thomas would walk through the halls of Clairton High School two years ago watching as students stooped over their cellphones, barely interacting with their peers.

The teens were often late to class, and incidents that started outside the Waddell Avenue school would sometimes filter in through text messages.

Knowing something needed to change, Ms. Allen-Thomas, the district superintendent, went through a process that eventually led to high schoolers for the first time last school year putting their phones in a secured envelope and bin at the start of the day and retrieving them after the last period. The process expanded a similar policy that was already in place for K-8 students.

“‘So tell me how has it been without a cellphone,’” Ms. Allen-Thomas asked students partway through last year. “They were like ‘Ah’ and then the kids said ‘Well, not that bad, actually. As a matter of fact I didn’t know such and such was even in my class. I talk to more people.’”

The Clairton City School District is among a growing group of Pittsburgh-area districts implementing policies to prevent students from using phones throughout the school day.

A sampling around the region shows Allderdice High School, Milliones 6-12 and Obama 6-12 in Pittsburgh Public Schools; Clairton, McKeesport, Penn Hills and Woodland Hills in Allegheny County; and Washington and Ringgold school districts in Washington County have phone-related policies or procedures.

“I like the thought of restricting access to phones in schools,” said Tom Ralston, University of Pittsburgh visiting assistant professor and former Avonworth superintendent. “Are there ways to utilize them in classrooms that can be valuable? Yeah, it can be a good learning tool as well.

“But … I believe, as an educator, that allowing the student to be immersed into a really creative learning experience in the classroom without a phone is a really valuable time, too.”

According to Mr. Ralston, conversations around cellphones in classrooms today are a natural progression of discussions that largely started when smartphones became popular. At the time, he said, phones “complicated things” by distracting students who wanted them “all the time.”

Teachers tried numerous ways to get students’ attention in the classroom such as requiring them to put their phones in calculator sleeves hanging on the wall and other ideas.

But problems persist. A recent study published by the nonprofit Common Sense found that 97% of study participants used their phones for a median of 43 minutes during school hours. Social media use took up 32% of that time. And cellphone use today comes as students continue to grapple with issues exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic such as attendance rates, low test scores and mental health.

Now, several initiatives are underway across the state and country to help students refocus.

In Pennsylvania, school districts can use state funding to purchase lockable bags that would secure students’ phones throughout the day. Other states, including Florida, Indiana, Louisiana and South Carolina enacted legislation limiting cellphone use during the day, The Washington Post reported.

Three other states — California, New York and Virginia — called on schools to restrict or ban cellphone use. And districts such as the Los Angeles Unified School District banned cellphone use while students in Clark County, Nev., have to use phone pouches.

At Clairton, Ms. Allen-Thomas spent most of the first year of her superintendency observing students and how they interacted with their phones during the day. She also sent surveys to district staff, parents and students. Afterwards, Ms. Allen-Thomas got approval from the school board to expand the cellphone policy already in place for K-8 students to the high school.

“First day of school was tricky,” Ms. Allen-Thomas said. “I was thinking ‘Oh my goodness there’s going to be an uproar.’ There was rumors that kids were going to boycott, all because of the cellphones. Well, lo and behold they came in, they were fine.”

As a tradeoff, Ms. Allen-Thomas permitted teachers to bring in old board games and the school uses table tennis and foosball tables before classes start each day.

“The pandemic really impacted the socialization of our students and so we have to get back to teaching those soft skills of being able to talk with people, look people in the eye, and how bout this — let’s play fairly,” Ms. Allen-Thomas said. “Let’s even engage on how to be a sore loser. So engaging in games and being able to play and just interact with their peers I think had a very good outcome at this point. This is year two. No worries.”

At Allderdice High School in Squirrel Hill, students starting this school year are required to leave their phones in a phone locker during class, according to the school’s student handbook.

“I didn't have really an issue with it because I think I was expecting phones to be collected at the beginning of the day and then not getting them back until the end of the day,” Allderdice senior Sophia Hall said. “So this seemed kind of like a better alternative [but] I'm not sure how effective it is.”

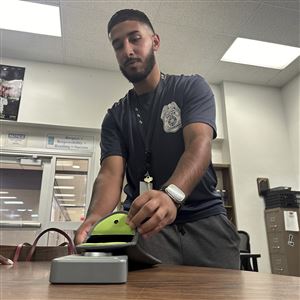

The school is now one of three in Pittsburgh Public Schools with phone policies. At Obama 6-12 in East Liberty, school officials use Yondr pouches, which locks cellphones in a pouch. They can be unlocked with a magnetic device. The decision came, Principal Yalonda Colbert said last year, after she spent 80% of her time dealing with drama created by phones.

Washington High School also uses Yondr pouches, Principal Roylin Petties said. When students walk in the building each morning, they show a group of teachers that the pouch is locked before going to class. Mr. Petties said the pouches have made a “world of difference” when compared to his former district that did not have a similar procedure.

“When I'm going into classrooms, students are engaged, they are focused, they're listening to their teachers,” Mr. Petties said. “Just a total difference. I mean, you walk into a classroom of 20 kids and 15 of them are on our cellphones … that's a little demoralizing for the teacher, but also that is showing that instruction is not happening.”

At McKeesport Area, school directors in May approved the purchase of 2,200 Yondr pouches for $60,100. They will be used at Founders Hall Middle School and the high school.

“We’re out in front of it and I think it’s a great idea we’re starting in Founders so by the time they get to the high school they understand the protocol and how we’re operating that program,” school Director Mark Holtzman said during the May meeting. “I think that’s going to eliminate a lot of things. … I think it’s a great idea.”

But several McKeesport community members are now pushing back against the idea, many of whom were displeased they wouldn't have constant access to their child.

Gillian Kuchma, whose son is a senior, is against the decision. She said he often uses his phone in addition to his school-issued Chromebook for classes. Ms. Kuchma called the decision “a frustrating thing. They're not really teaching the kids to be responsible. The kids feel it's a punishment.”

Nicole Florenz, the mother of elementary, middle and high schoolers, listed concerns with transportation and safety — instances where her children would need their phones. Ms. Florenz, who moved her children into the district from a Catholic school, said there have been a number of times where her older daughter has been impacted by fights or other instances at the school.

“At baseline, there's anxiety every day dropping them off like, ‘Be safe, have a great day,’” Ms. Florenz said. “Heaven forbid if there would be an emergency, OK, great, you have your phone on you but you can't access it.”

And this year Woodland Hills put processes in place at the high school to comply with a cellphone policy, a decision that came after back-and-forth between school directors.

The procedures, which require students to put their phones in a secure bin, were requested by high school administrators who said during an April meeting that this is the next step after officials worked to change the high school culture.

“This is not a punishment,” the district’s website reads. “It is an opportunity to help our students refocus on the education they receive throughout the school day.”

Like McKeesport, Woodland Hills families have had mixed reactions to the extended policy.

Kimber Lovell suggested that her daughter, a high school junior, waits 30 minutes each morning to go through metal detectors and to hand over the phone.

But parent Chris Ansell countered, saying he’s in support of the policy. Mr. Ansell has three children in the district, a first grader, a seventh grader and a high school freshman.

“This is a new program,” Mr. Ansell said. They are working to try to increase their efficiency of how they do all this. But I think it's a very important program for high schools, wherever they're located, to participate in.”

First Published: September 1, 2024, 9:30 a.m.

Updated: September 1, 2024, 10:23 p.m.