As testimony continued Tuesday about Robert Bowers’ youth, defense attorneys began introducing witnesses who would paint the Pittsburgh synagogue shooter as something more than a victim of his childhood circumstances: a person.

Long before his name was linked to the carnage he wrought on the Squirrel Hill synagogue where Tree of Life, Dor Hadash and New Light congregants worshipped, he was a kid living in a South Hills apartment complex who spent his days running around with the other kids.

That group of friends, brought together by proximity, included Frank Ray. On the witness stand, Mr. Ray remembered Bowers as smart if not a little odd. Bowers is also someone who Mr. Ray believes to this day, some 40 years later, saved his life.

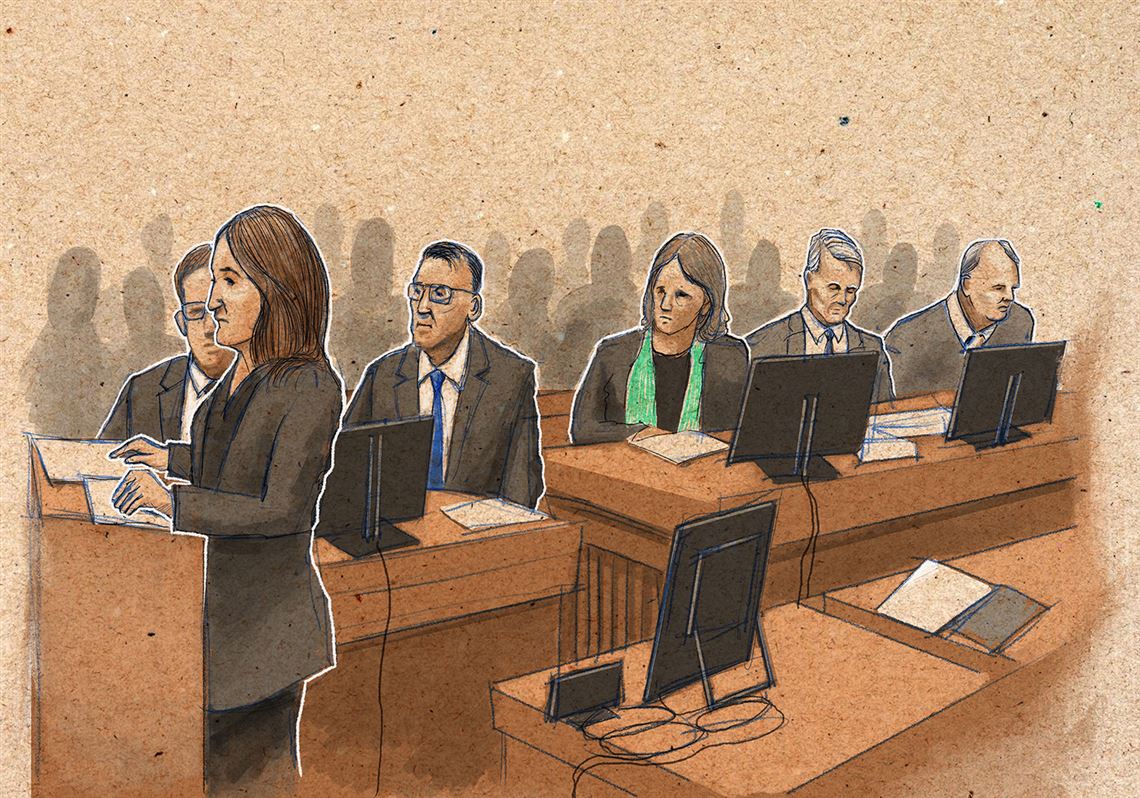

Defense attorneys for Bowers are in the midst of presenting their mitigating evidence as jurors in the case near their final decision in the trial: Whether Bowers should spend life in prison or be sentenced to death.

Those same jurors convicted 50-year-old Bowers of all 63 federal charges against him last month. He killed 11 people in his Oct. 27, 2018, rampage through the synagogue at the corner of Shady and Wilkins: Joyce Fienberg, Richard Gottfried, Rose Mallinger, Jerry Rabinowitz, Cecil and David Rosenthal, Bernice and Sylvan Simon, Daniel Stein, Melvin Wax and Irving Younger.

Prosecutors presented their case for the sentence-selection phase last week, presenting testimony they said showed the crime was so heinous that Bowers deserves the death penalty. The defense is now in the midst of reconstructing Bowers’ childhood and the person he was before 2018 in a bid to mitigate that heinousness.

Among the witnesses Tuesday were since-retired social workers and other employees from inpatient facilities Bowers was committed to in his teens. None remembered him personally, although they added context to medical records and reports from his time there.

Mr. Ray, of Whitehall, testified for about 30 minutes Tuesday morning, telling jurors how Bowers had a bit of a reputation as the kid who knew how to blow things up.

That reputation preceded him, and Mr. Ray heard about the kid named Rob who could make explosives before he even moved into the apartment complex.

“When you’re 13, it’s quite entertaining to blow up toys,” he said.

The explosives, which included pipe bombs, he said, were never targeted toward anyone, and no one ever got in any real trouble for it. He recalled Bowers once making a gun out of some bicycle handlebars, and he remembered a makeshift cannon being fired once or twice.

As older teens, Mr. Ray said, the group drove to the Glenwood Bridge where they’d heard there was a rope swing underneath. They spent hours swinging and jumping into the Monongahela River. As the sun set, he said, everyone began to swim back to shore.

“I was kind of sinking,” Mr. Ray said. “I was fairly certain I wasn’t going to make it.”

Friends on the shore told him to swim harder. Bowers, he said, jumped back in and swam out to him. Putting an arm under Mr. Ray’s shoulder, he told him to relax, and swam him back to shore like a lifeguard.

“No worries, let’s go,” he told Mr. Ray when they got back to shore.

“I’m fairly certain I would not have made it to shore if he hadn’t been there,” Mr. Ray told jurors. “He probably saved my life that day.”

The witness also offered jurors a glimpse into Bowers’ life at home with his mother, who defense attorneys have painted as a neglectful parent who had poor boundaries and exposed her son to domestic violence by way of the company she kept.

Mr. Ray said the Bowers’ apartment was dimly lit, and his mother was an overweight woman who moved slowly all the time. He said she seemed downtrodden, with a “woe is me” attitude.

“It was very uncomfortable being around her,” he said. “She seemed barely able to function.”

The handful of times Mr. Ray went to his friend’s apartment, Bowers’ mother would be in the shower with a TV cart parked in front of the open door. He and Bowers would leave for a while, an hour or more, and when they came back, she was still in the shower.

“I could feel his embarrassment,” Mr. Ray said of Bowers.

The two grew apart, but Mr. Ray said he recalled hearing that Bowers was severely burned in an incident some years later. He’d been drinking grain alcohol and ended up setting himself on fire. Mr. Ray said there were two rumors: One was that Bowers tried to kill himself, and the other was that it was a drunken accident involving the alcohol and a cigarette.

It was after that incident, which happened in late 1989, that fellow Baldwin-Whitehall student Kelly McKinley befriended Bowers.

Though she’d never spoken to him or had any previous relationship with him, she said, she went to UPMC Mercy to visit him after the grain alcohol incident.

“I felt really bad,” she told jurors in her testimony via Zoom. “I’m a very loving and caring person.”

Ms. McKinley, who now lives in North Carolina, said Bowers was wrapped in gauze with just his eyes left showing. They were red and swollen. He couldn’t talk and he used a white board and marker to communicate. Even that was hard though, she said, as his hands and arms were also burned.

Among the words he wrote to her: “grain,” “alcohol,” and “cigarette.”

When she visited a second time, Ms. McKinley said, he wrote “I love you.”

“I did not expect that,” she testified. “I did not know him. I hadn’t really spoken to him before that.”

He was admitted as an inpatient to the psychiatric ward at the former St. Francis Hospital in Lawrenceville after he was released from Mercy. When Ms. McKinley visited him there for the first time, she said, he hatched a plan to escape the in-patient facility.

She agreed to go along with his plan. They put it into action the next time she visited him on Jan. 13, 1990.

Bowers was out of St. Francis on a home pass that day. Bowers’ mother was driving her son back to the facility, and Bowers and Ms. McKinley were in the backseat. When Bowers’ mother stopped at a stop sign, each teen threw open their door and took off running.

Both were ultimately caught by police. Bowers was returned to St. Francis and Ms. McKinley to her parents. A police report identified Ms. McKinley as Bowers’ girlfriend. She said she was never his girlfriend, and she never told him she loved him.

Ms. McKinley said she saw Bowers once after that. He showed up in her backyard — she unsure if she’d invited him or not — and they sat against the outer wall of her home, talking and smoking.

Bowers was upset, she said. He didn’t like his mother and he didn’t like his stepfather. He also told her the grain alcohol incident was an accident, not a suicide attempt.

Some of Bowers’ former co-workers also testified Tuesday afternoon.

Jason Erb, the director of operations at PAM Transport, a trucking company where Bowers worked in 2015 and 2016, said Bowers kept his truck clean was scored well on his written and road tests. He quit after a year for a driving job that didn’t require such long hauls.

Michael McLellan, of the South Hills, was Bowers’ supervisor at Community Living and Support Services, an Edgewood-based organization that provides in-home care to people who are elderly, disabled or in otherwise in need of home assistance.

Bowers worked there in 2010 and 2011. His aunt worked there, too.

Performance reviews from the time showed Mr. McLellan found Bowers to be an exceptional employee. He was assigned to two specific men who needed in-home assistance that other caregivers had trouble getting along with.

Both men had traumatic brain injuries, he testified, and Bowers would go out of his way to spend extra time with them, take care of things around their homes and overall make an extra effort in offering care.

“He seemed to try to go above and beyond,” Mr. McLellan said.

Assistant U.S. Attorney Soo C. Song, during prosecutors’ cross-examination, asked both witnesses about the qualifications for each job. She asked if employee at either company would have to be responsible, reliable, trustworthy — not someone living on the fringes or society or just minimally functioning? Both men said that was accurate.

Testimony continues Wednesday morning.

Megan Guza: mguza@post-gazette.com

First Published: July 25, 2023, 11:24 p.m.

Updated: July 26, 2023, 4:15 p.m.