When 45-year-old Tiwan Hill was found shot dead in a Hill District apartment last month, police and the medical examiner’s office released his name and an address, but little else.

To those who knew Mr. Hill, his life meant more than that.

“I grew up with him, we grew up in the same community,” said Tonia Jones, a Hill District native. “He was very close to my family.”

Mr. Hill’s death was just one of 11 shootings — two of them fatal — that echoed through the historic African American neighborhood since March 22. For some neighbors, the location and scale of recent shootings are surprising, though the grisly realities of gun violence have become just another part of life.

“I’ve gotten desensitized to it,” Ms. Jones said. “It’s sad to say, but more or less, when I see it or hear about it, I feel sad for the family. But other than that, it’s like, what can you say and what can you do?”

In the wake of the recent violence, neighbors described to the Post-Gazette a Hill District that over decades has suffered from systemic inequity, widespread poverty, lackluster education and mental health care, and a lack of good jobs and housing, leaving young people with few opportunities.

They blame politicians, schools and other institutions for not doing enough to support the community, pointing to the closing of recreation centers and the shuttering of church-related activities.

Ms. Jones, 51, grew up in Elmore Square, an area now known as Skyline Terrace. Like that neighborhood’s name, Ms. Jones has watched the entire community change over decades, as it continues to face gun violence at higher rates than nearly all others in Pittsburgh.

Outside Calvary Baptist Church on Wylie Avenue on Thursday, Ms. Jones and Rhoda Montgomery, a 65-year-old Hill native, were helping to unload fresh produce and flowers from the back of an SUV for a monthly food bank.

Just two days before, on April 12, three men in their 20s were shot near the intersection of Wylie Avenue and Watt Street, a block from where the women stood. The shooting left one man in critical condition, while bullets chipped the side of a home and punctured the windshield of a vehicle nearby.

“I get what they call a news break on my cell phone,” Ms. Jones said of the shootings. “And every time it pops up — as soon as they say Pittsburgh — the only two neighborhoods that really jump up are Homewood and the Hill District.”

Lack of accountability

The triple shooting was in a section of the Hill District that contains a popular diner and is less than a block from St. Benedict the Moor School.

But if gun violence is going to occur, it’s bound to happen here, too, said Dorian Moorefield, owner of Grandma B’s Café at the corner of Watt and Wylie.

“If it can happen in a mall, if it can happen in places like Squirrel Hill and the South Hills ... it’ll happen over here,” Mr. Moorefield said.

Mr. Moorefield has run his restaurant for a dozen years as the neighborhood around him experienced countless shootings and other violent events. The past month and a half has been particularly brutal.

Pittsburgh police have reported 13 people have been shot in the Hill District since March 1, including three who died.

The latest shooting occurred late Friday. A police statement said officers responded to a report of shots fired in the 2000 block of Centre Avenue about 10:30 p.m. They found a man lying in the street at Centre and Addison Street with at least one gunshot wound in the leg.

And there have been various other violent incidents such as stabbings and assaults. In the same time period in 2021, just two people were shot in the neighborhood.

Mr. Moorefield points to the same root causes of violence that many Hill District residents mention — poverty, lack of education, little opportunity. But he also says the people committing the violence lack accountability — to themselves, to others and to a higher power.

Mr. Moorefield credits finding religion for changing his life.

When he was younger, he said, he was in the streets and involved in criminal activities. After learning the tenants of Islam and discovering that he would be held accountable after his life for everything he said and did during his life, he realized that he needed to alter his behavior.

Many young people, though, don’t have that kind of epiphany, he acknowledged. He said he’s surprised there isn’t more violence.

“It could be worse than this with these types of psychos running around here, with these types of weapons, with nothing to lose,” Mr. Moorefield said. “It could be much worse. We’re getting away with living amongst people who believe they don’t have anything to live for. They don’t have anything to live for, so if they don’t care about themselves, why would they care about me and you?”

Mr. Moorefield also pointed to what he described as a loss of faith in institutions, such as schools, city government and police. He places blame on the communities, too, for not being more proactive in their approach to stopping violence.

He said what is needed is “some type of community involvement from whoever is responsible in those respective communities, trying to find these youth and talk it out. But we usually come [together] when there’s a body lying in the streets.”

Still, he relates small instances that give him hope that things can change — customers who come in and tell him that they remember what he was like when he was younger and say they want to turn their lives around, too; children who stop to listen to what he has to say.

Change is not going to happen overnight, he said, but it is possible.

He gave kudos to Mayor Ed Gainey for coming to the diner and the surrounding area the day after the triple shooting to console residents and offer words of encouragement.

“He came in to check to make sure we were OK, and he went to people’s houses all around here,” Mr. Moorefield said. “It was beautiful.”

Mr. Gainey said he also went to speak with neighbors on nearby Chauncey Drive after a shooting a few days earlier.

“We were talking to the people, and my question to them was, ‘Tell us how the city can help you?’” Mr. Gainey said. “Same story. The guns. The drugs — meaning young people with the pills and the whole drug situation. You know, there’s an overdose every day in this city. And so dealing with the drugs is major. Dealing with these guns in our community is major.”

The mayor, who is less than four months into his term, said his administration is working on short- and long-term initiatives for curbing gun violence.

“I just think that were seeing what happens when you see cities flooded with guns,” Mr. Gainey said. “But we’re going to do all we gotta do. We’re having talks every Saturday now. We will start rolling some things out.”

Products of the environment

Ms. Montgomery reflected on the Hill District of her youth in the 1980s, a period when, she says, young people didn’t have as much free time to get involved in criminal activity. She thinks that today, the children who grew up in the wake of the crack epidemic of that period have lost connections to their parents and their communities.

She and Ms. Jones said that back then, the Hill had thriving recreational centers, churches, playgrounds — amenities that have closed or been replaced with facilities that are run more like businesses.

“There was more mentorship back then, even if we didn’t realize we were being mentored,” Ms. Montgomery said. “Bible class during the summer.”

“You have these young kids going to jail, and then when they come out, there is nothing out here for them to constructively get into,” Ms. Jones chimed in.

Now, even children in school and daycare aren’t always safe.

On March 29, a stash of guns was found in an abandoned house near Milliones 6-12 in the Hill District, prompting a modified lockdown at the school.

Jordan Lewis, 28, of Penn Hills, who works at a daycare facility inside the Hill House Center, said twice in recent weeks she has had to bring children from an outside playground indoors following nearby gunfire.

“You’re guaranteed two safe places: your home and school,” Ms. Lewis said. “If you don’t have a safe place at home, your safe place should be at school. Unfortunately, these things happen outside of your control.”

Ms. Jones and Ms. Montgomery both said they believe politicians could do more to change the conditions that lead to poverty and violence.

Ms. Montgomery criticized Pittsburgh City Council for focusing on issues besides the recent shootings, pointing to council’s recent vote to ban the use of plastic bags that’s set to go into effect next year.

“You ain’t got nothing else better to do than worry about a plastic bag?” Ms. Montgomery said with frustration. “You’ve got people around here killing each other.”

Elloitt Kimbo, 60, of the Hill District, said government at every level has failed to help people.

How can so many people live in poverty in one of the richest countries in the history of the world, he asked.

“The war in Ukraine [showed] they can allocate millions and billions of dollars. Even the pandemic showed us that the United States is very wealthy,” Mr. Kimbo said. “If they really wanted to change poverty in America, they could do it with a stroke of a pen.”

Some say that at least part of the fault lies at home.

Denise Bazemore, 72, a retired security guard, said she raised her son and daughter with an “iron fist,” and they have become productive members of society with their own families, she said.

But that doesn’t always happen, she said.

“The mother’s too busy with the wig stores, and the nail salon, and booty shaking and all that instead of being home raising their kids,” Ms. Bazemore said. “I raised my kids.”

But some say the issues at home — and in general — are part of a larger cycle of societal failure that has allowed generation after generation to be lost to drugs and violence due to neglect from institutions and individuals in power.

Hill District native Danier Gordon, 50, a jitney driver, said youth are merely a product of their environment.

“It’s really not their fault. If their mother’s on drugs and their daddy’s locked up, then who’s going to raise them? Who’s going to raise these young Black boys out here?” he said.

“People don’t care. They’ll walk by them looking at them like they ain’t nothing. They can’t help where they come from, they were dealt a bad hand.”

Government action

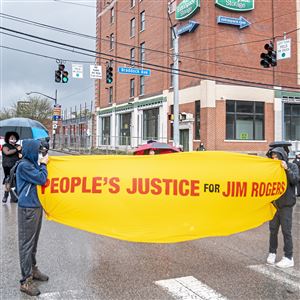

As the shootings increased, state and local politicians along with law enforcement have come together in several Pittsburgh neighborhoods to hold rallies against gun violence.

The week following the triple shooting deaths of 23-year-old Micah Stoner in Mount Washington, 29-year-old Devonte White in Brookline, and 15-year-old Dayvon Vickers in Homewood, Mr. Gainey and Pittsburgh police Chief Scott Schubert, among other local leaders, attended two rallies.

While Ms. Jones and Ms. Montgomery aimed frustration at Mr. Gainey and Jake Wheatley, the former state representative for the 19th District covering the Hill and Mr. Gainey’s chief of staff, the area’s newly elected political leader, Rep. Aerion Abney, offered a response to the violence.

“I am eager to use my voice in the Pennsylvania House of Representatives and — loudly — advocate for long overdue, sensible firearm policies that will prevent future tragedies in Pittsburgh,” Mr. Abney said.

Mr. Abney said there are more than 100 bills on file in Harrisburg that would address gun violence and the social issues that cause it, though most of them remain stalled in committees.

“I understand the legislative process is slow,” Mr. Abney said, “but it’s past time to urge the folks in Harrisburg to understand the urgency that our community feels in addressing gun violence and the systemic issues that cause it.”

Staff writer Julian Routh contributed. Jesse Bunch: jbunch@post-gazette.com.; Andrew Goldstein: agoldstein@post-gazette.com.

First Published: April 16, 2022, 4:15 a.m.

Updated: April 16, 2022, 9:20 p.m.