The Allegheny County District Attorney’s Office on Wednesday denied allegations of prosecutorial misconduct in the Wilkinsburg mass shooting case, responding to a blistering attack by the defense in a motion that was unsealed earlier in the day.

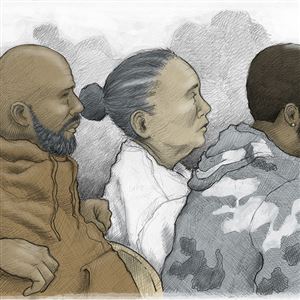

The motion, filed Friday by defense attorneys for Cheron Shelton, who is on trial for the 2016 mass slaying, was initially put off limits to the public by Allegheny County Common Pleas Judge Edward J. Borkowski, who said he needed to review it to ensure there was no protected information, such as grand jury material.

Lawyer Randall McKinney wrote that he learned only last week that an initial jailhouse witness, whose information provided crucial material for the affidavit of probable cause that led to charges in the case, was paid thousands of dollars by law enforcement, which was never revealed to the defense.

According to the motion, Kendall Mikell, referred to in court documents as Witness No. 1, was paid cash “off the books on multiple occasions,” was told to implicate Shelton by fabricating statements, and was told to lie on his proffer video about leniency.

Shelton’s attorney alleges that the lies encouraged by prosecutors were incorporated into the arrest warrant in the case, therefore making it invalid.

“The prosecutorial tactics in this case can only be characterized as ‘egregious.’ Only via a mistrial can this court be ensured that a jury not convict defendant — and potentially sentence him to death — based on unethically procured and falsified evidence,” according to the motion.

After hearing arguments on the motion Friday, Judge Borkowski denied Mr. McKinney’s request for a mistrial for his client, who is charged with multiple counts of homicide in the March 9, 2016, slayings at a backyard cookout on Franklin Avenue.

The judge did not explain his reasons other than alluding to the complexity of hearing testimony about the allegations and saying he would not let the witness “blow up or terminate this trial or even delay it.”

_____________

_____________

In the DA’s response, the lead prosecutor in the Wilkinsburg case called Mr. McKinney’s motion a “desperate attempt on behalf of the defense to influence a jury that has not been sequestered during deliberations in this matter.”

Referring to the witness as “Person No. 1” because he did not testify in the case, Deputy District Attorney Kevin Chernosky denied that the man “was prompted, prodded, instructed, directed or requested in any manner to provide fabricated information against Cheron Shelton.”

Mr. Chernosky also denied that undocumented payments were made to the witness regarding the case and called the defense filing “unfounded and frivolous.”

As the war of words in court papers played out, the jury wrapped up its second day of deliberations after hearing six days of testimony. They left the Allegheny County Courthouse around 4 p.m. and are expected to resume Thursday. Shelton, 33, of Lincoln-Lemington, could face the death penalty if convicted of first-degree murder.

Mr. McKinney’s filing marked the second time that Shelton’s lawyers alleged misconduct by the DA’s office in paying confidential informants for information about the Wilkinsburg case but not revealing that to the defense.

Over the past four years, prosecutors had three potential unnamed witnesses set to testify against Shelton and his former co-defendant, Robert Thomas. But they scuttled the use of all of them, making the decision on the final one, known as Witness No. 3, just before trial. That led the judge to dismiss the case against Thomas for lack of evidence.

Defense attorneys for Shelton and Thomas alleged that the prosecution withheld crucial discovery information — that Witness No. 3 had been made promises in return for his cooperation — that hampered their ability to properly impeach him on the stand.

Judge Borkowski released not only Mr. McKinney’s motion but an accompanying 61-page transcript of an interview with Mikell, conducted Feb. 5 by Mr. McKinney.

According to that transcript, Mikell was in the jail in the spring of 2016 when he met Thomas and the two spoke. That conversation led Mikell to reach out to internal affairs there. He was then asked to further engage with Thomas, which he told Mr. McKinney he did.

Later, he said, he met with his attorney, Chris Eyster, the detectives and Allegheny County Assistant District Attorney Lisa Pellegrini.

Mikell said in the transcript that Ms. Pellegrini tried to bully him into cooperating against Thomas and Shelton, and that his attorney, Mr. Eyster, urged him to cooperate.

“He was like, ‘you’re about to talk to the prosecutor. She’s the top dog. And she’s like, she’s a pit bull. So just be respectful and listen to what she got to say. She got a lot of power,’ ” he told Shelton’s defense attorneys.

He said when he met with Ms. Pellegrini, she told him there were six victims in the Wilkinsburg case, and that they couldn’t mess it up.

Five adults and an unborn child were killed in the shooting, which prosecutors allege resulted from a vendetta that Shelton had against a family member of the victims who was at the barbecue. Three other adults were wounded, including the alleged target, Lamont Powell.

“I’m like, ‘I’m not agreeing to testify,’ ” the witness said he told them. “ ‘This case is too crazy. I’m not getting involved on that level.’ I said, ‘I’m already in danger out here.’ ”

Mikell said he left the room, and Mr. Eyster continued to talk to Ms. Pellegrini. Mr. Eyster then told the witness that if he didn’t cooperate, his probation could be violated, and he could go to prison for seven years.

On July 29, 2016, the day of the preliminary hearing for Shelton and Thomas, Ms. Pellegrini told Mikell they weren’t going to call him.

“She’s like, ‘What do you want? I got county money. I got state money. I got federal money. I got unlimited funds for this case. What do you want?’ ”

He said they were also “feeding” him information about the Wilkinsburg case.

He said the detectives told him they wanted to “put together a grid of events,” and that they had Shelton on a camera jumping a fence.

Prosecutors introduced more than an hour’s worth of surveillance video of three public housing complexes in Homewood on the night of the shooting, which occurred at 10:53 p.m., and the early morning hours afterward. The complex, where Shelton’s mother lived, is where they allege that Shelton hid ammunition, obtained the rifle used in the shooting and returned afterward, jumping a fence as he went back to his mother’s townhouse.

It was only after Mikell had been released from jail and then picked up by police in McKeesport in November 2016 that the witness claimed he was housed next to Shelton at the jail.

“I didn’t go to a pod. I was sent directly to the hole right next to Shelton. My cell was directly next to him. I don’t know how they did it, but they arranged for me to go next to him and wanted me to have a conversation with him regarding his case and gather anything that I could.”

The witness told the attorneys that once he was in that cell, he started talking regularly to Shelton.

“[O]nce I got to talking to him, I didn’t want to do it,” he said. “I couldn’t go through with it. And he just kept saying he was innocent, and I said, ‘Man, I’m not doing this.’ ”

The transcript does not make clear when Mikell started to receive payments, but said he was working with county police and the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives.

Included in the remuneration was placement in an extended stay hotel and $300 for groceries.

Then, Mikell said, he was told to contact them every two weeks for more money.

“So eventually, they end up giving me money to get my own apartment and everything. Security deposit and the first three months rent,” he said, according to the transcript.

“It was different detectives every time.”

At one point, he said, $2,700 was wired to him at a Walmart in West Virginia.

“I was given money for groceries. I was given coffee money, a hundred dollars here and there if I needed something from detectives.

“Sometimes I signed for it.”

It was some time after June 2017 when prosecutors decided they would not call Mikell at trial.

In his motion, Mr. McKinney wrote that the conduct he alleges might be less egregious if there were other strong evidence — like eyewitnesses or a confession — against his client.

“But in the absence of such evidence, this witness simply takes on a more critical role in the prosecutor’s case, making the non-disclosure of impeachment evidence that much more problematic.”

“The pattern of misconduct not only characterizes the entirety of this prosecution but also leaves the defendant and the court wondering: what other discovery violation has the prosecution committed? The commonwealth’s wrongdoing contaminates the entirety of this case.”

The DA’s response Wednesday denies paying informants “directly” for information. Instead, Mr. Chernosky wrote, the commonwealth gives “financial assistance” for witness protection.

The prosecution provided a timeline of the witness’s history of cooperating with authorities after being federally indicted in 2013. He provided information on a 2014 murder; he did not testify, and both defendants were acquitted. A year later he gave information about another murder and testified at a preliminary hearing. The accused was acquitted.

With regard to the Wilkinsburg case, the DA’s office said the witness got a confession from Thomas in the Allegheny County Jail on April 6, 2016. He contacted jail investigators and was interviewed by county police.

Detectives told the witness on June 20, 2016, that his information would be included anonymously in the affidavit supporting the arrests of Shelton and Thomas. He declined relocation at that time, the DA’s office said, but requested relocation that November.

He filled out paperwork for witness relocation through the state Attorney General’s office, and his housing was directly billed to that program, the DA’s office wrote. The witness was arrested 11 days later on drug and assault charges and sent back to the jail; he was removed from witness protection at that time.

The witness contacted police and Ms. Pellegrini, the other prosecutor on the Wilkinsburg case, and told them he feared for his life and threatened to go to the media if he didn’t get protection.

The attorney general’s office denied a request for money to rent an apartment, so the DA’s office agreed to pay $1,756 from its own witness relocation fund.

“This was done to further protect the witness, even if the commonwealth did not use him, because of the number of cases he had participated in,” the filing said.

The money was wired to the witness on April 6, 2018.

During the hearing Friday, Mr. McKinney asked that Ms. Pellegrini be disqualified because she would potentially be called as a witness based on her interactions with the jailhouse informant.

At the hearing, Mr. Chernosky disputed Mr. McKinney’s characterizations.

“First and foremost, the allegations by Mr. McKinney that anyone from the district attorney’s office or from the Allegheny County Police Department told this witness facts of the case and asked him to get close is an absolute fabrication,” Mr. Chernosky said.

Paula Reed Ward: pward@post-gazette.com, 412-263-2620 or on Twitter @PaulaReedWard. Jonathan D. Silver: jsilver@post-gazette.com, 412-263-1962 or on Twitter @jsilverpg.

First Published: February 12, 2020, 3:34 p.m.

Updated: February 12, 2020, 4:00 p.m.