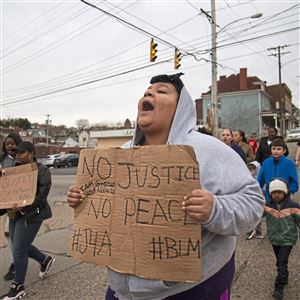

A day after a jury found former East Pittsburgh police officer Michael Rosfeld not guilty in the death of 17-year-old Antwon Rose II, a crowd of protesters upset about the verdict faced a line of police officers in Oakland.

The half-dozen officers stood atop a set of steps on Fifth Avenue. Two young men with bullhorns and a young woman stood on the stairs in front of the officers, shouting, “Who did this?”

The crowd of protesters answered, “The police did this!”

The officers — none of whom wore riot gear — stayed put as the crowd shouted, “Shame, shame shame.” And after three minutes, the large group of protesters kept marching.

That protest — like all the demonstrations in Pittsburgh during the week following the not-guilty verdict — was peaceful, civil and without arrests.

It’s a credit to both law enforcement and the community, local and national experts said as they watched the week unfold. Pittsburgh police and city officials deliberately tailored the law enforcement response to avoid escalating an already tense situation, and protesters have taken pains to avoid violence or property damage.

“It’s a two-way street,” said Meagan Cahill, a senior policy researcher at the Rand Corporation. “But already having this experience under their belt — for both the community and the police — is a positive thing and cause for some cautious optimism looking forward.”

Local law enforcement — including Pittsburgh police, the sheriff’s office, county police and the Pennsylvania state police — began to plan for anticipated protests months before the jury acquitted Mr. Rosfeld of homicide on March 22.

“We knew people would be upset about a not guilty verdict, so we had to be very cautious how we handled it if that happened,” Allegheny County Sheriff William P. Mullen said. “The strategy was to give protesters great leeway.”

The agencies learned from the FBI that outside agitators weren’t expected to come to Pittsburgh after the verdict, making violence less likely, Sheriff Mullen said. Law enforcement also reached out to local protest leaders to build relationships and foster communication before the verdict was rendered.

Officials decided to avoid sending officers to the protests in riot gear and to keep the visible number of officers on the streets to a minimum — although large numbers of officers were stationed out of sight nearby, ready to move in if the demonstrations turned violent, Sheriff Mullen said.

“I think the philosophy in coming out without personal protective equipment is to show we’re not here acting as soldiers,” he said. “We are police officers who share the same community as the protesters. We’re not an invading army.”

Riot gear and a heavy police presence can unnecessarily inflame a crowd, said Chris Burbank, former police chief in Salt Lake City and now a vice president for strategic partnerships at the Center for Policing Equity, a nonprofit think tank.

“I’m convinced if you show up and your first response is riot gear, then that just screams, ‘Throw rocks and bottles at us,’” he said.

Although no officers in Pittsburgh used riot gear, some of the other security measures used by police during and after the trial, like blocking streets with snow plows and using officers on horseback, did raise concern among some protesters.

“We feel threatened. We don’t feel comfortable. We feel like all of that extra security and patrols are unnecessary,” said community organizer Tiffani Monique Walker, who added she felt the increased police presence was meant to intimidate demonstrators.

“They really thought we were going to burn the city down,” said Ashley Palmer, also a community organizer. “We were never about that. None of the protest organizers or protesters have gone on social media or talked privately to incite violence. We were asked by Antwon’s mother and father to remain peaceful, and we respected their wishes.”

Neither Ms. Palmer nor Ms. Walker felt the police response to the verdict brought much cause for optimism, despite the lack of violence or arrests.

“We chant and we march and nothing happens after that,” said Ms. Walker, whose father died in a police vehicle in 2000. “There’s nothing new under the sun when it comes to this.”

But Pittsburgh Mayor Bill Peduto, who said the snowplows were used to prevent anyone from driving into the demonstrations, said he saw more communication between police and protesters in this situation than in years past.

“In particular, we have a very new command staff, a lot of people who are younger are now part of our leadership of this bureau, and they have taken it [upon] themselves to be more connected with the community, more so than I’ve seen in over 20 years of working in city government,” he said.

The protests are expected to continue for several weeks, Mr. Peduto said, but he’s encouraged by the city’s approach so far.

“We’ve been able to learn a lot from those who are at the front of the demonstration, and I think they’ve come to understand that the city recognizes the sensitivity of this issue,” he said.

The more measured approach by Pittsburgh law enforcement to these protests can help rebuild community trust in police, experts said.

“Especially in black and brown communities that have felt nothing but oppression from police,” Mr. Burbank said. “We’ve been very good at oppression over the years. And things like this are a step in the right direction as to what police should be doing all the time.”

Pittsburgh was on edge in the wake of the verdict, said Leonard Hammonds II, a community organizer, and he was glad to see police giving protesters room to vent and be heard, especially during the large student march.

“They’re exercising restraint on some levels, and operating from a place of, ‘Lets not add any fuel to the fire,’” he said. “And I think they’re thinking things through a little more. But I think the same energy they put into policing these protests they need to put into policing our community.”

That sort of consistency and longevity is also critical to rebuilding community trust, Mr. Burbank said.

“You can’t just rise to a few occasions,” he said. “You need to make sure that on the traffic stop at 11 p.m. with one officer on a deserted street, the same professionalism is there that existed when you were on TV with a bunch of protesters.”

Elizabeth Pittinger, executive director of the city’s Citizen Police Review Board, said she’s seen a broader cultural shift inside Pittsburgh police during the last several years that has seemed to create greater patience and discipline when dealing with protests and demonstrations.

“It’s been evolving over the last 20 years,” she said, adding that Pittsburgh’s participation in the National Initiative for Building Community Trust and Justice, a federal program that focuses on reducing police bias and improving community relations, has contributed to the cultural change.

“That really focused on community reconciliation and it focused on the whole notion of implicit bias and procedural justice,” she said. “Emphasizing and highlighting those two concepts through police training, and getting it out in the community, I think has made a difference. It’s raised people’s awareness of some of the attributes that create the tension and the perception of inequity in the system.”

The review board hasn’t received any complaints about Pittsburgh police in connection to the demonstrations after the trial or the protests that followed the June shooting, Ms. Pittinger said.

“Now they’re using their brains and being more aware and sensitive to the circumstances that bring people to our central city,” Ms. Pittinger said of police. “And they’re responding in a way that is sensitive to First Amendment rights and community awareness.”

Tim Stevens, chairman and CEO of the The Black Political Empowerment Project, said he generally felt Pittsburgh police did a good job as they responded to the verdict, which he called “outrageous,” and said he hopes the case will push state politicians to change laws that give wide authority to police to shoot people fleeing suspected felonies.

“Sometimes negative moments in history, with regards to policing, lead to changes that are needed and often significant,” he said.

Shelly Bradbury: 412-263-1999, sbradbury@post-gazette.com or follow @ShellyBradbury on Twitter. Reporters Michael A. Fuoco and Ashley Murray contributed.

First Published: March 31, 2019, 12:00 p.m.