Death penalty cases are relatively rare in the federal courts system and executions even more rare.

Only three people have been executed since the federal death penalty was reinstated in 1988; the vast majority of the nation's capital cases are handled at the state level.

But in either jurisdiction, the appeals process is long and involved and the will to impose the ultimate sanction seems to have dwindled over the years.

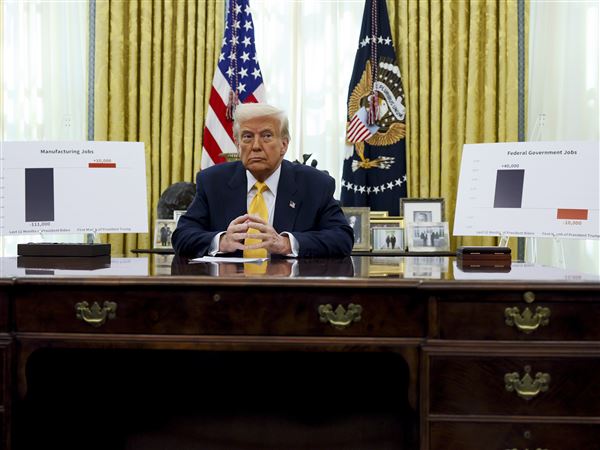

President Donald Trump supports the death penalty but it's not clear if that will translate into more federal executions.

If it does, accused synagogue shooter Robert Bowers would seem to be a likely candidate for lethal injection at the federal death chamber in Terre Haute, Ind.

He is only the fourth defendant in the history of Western Pennsylvania's federal district, which comprises 25 counties, to face the federal death penalty.

None of the others was executed.

The only three federal inmates to be put to death in modern times are Timothy McVeigh, Juan Garza and Louis Jones, all of whom were executed in the early 2000s when George W. Bush was president.

McVeigh, who blew up the Oklahoma City federal building in 1995, was executed in 2001. Garza, a marijuana dealer who killed three other dealers in Texas in 1993, was also executed in 2001. And Jones, a Gulf War veteran who kidnapped and murdered a female soldier in Texas in 1995, was executed in 2003.

In all, 78 defendants nationwide have been sentenced to death since 1988.

Three locals - Joseph Minerd, Lawrence Skiba and Jelani Solomon - have all faced possible execution initially but none was sentenced to death.

Minerd was the first.

In 1999, he used a pipe bomb to blow up a house in Connellsville to kill his pregnant ex-girlfriend because she refused to get an abortion. Her 3-year-old daughter also died. A federal jury in Pittsburgh convicted him but spared him execution in 2002. Now 63, he is serving life at a federal prison in New Hampshire.

Lawrence Skiba of White Oak hired a hitman to kill a McKeesport used-car dealer in 2000 so he could collect insurance money. He originally faced the death penalty but pleaded guilty and cooperated against the hitman, Eugene DeLuca, in exchange for the chance to get out of prison someday. Now 65, he's due to be released from the federal prison in Loretto, Pa., in 2020.

Jelani Solomon of Beaver Falls ordered the 2004 contract killing of a witness against him on the eve of his drug trial. A jury convicted him of using a gun during a drug trafficking crime resulting in death and conspiracy to distribute cocaine but spared him the death penalty. Now 39, he is serving two life terms at the federal prison in McKean.

No one can say if Mr. Bowers will end up on federal death row.

But David Harris, a University of Pittsburgh law professor, said the Justice Department is more likely under Mr. Trump to pursue the death penalty in general and that fact alone increases the odds that someone - maybe Mr. Bowers - will be executed someday.

Still, the final decision is in the hands of a jury, not a prosecutor or a judge. And in some instances the victims may not want the death penalty. Prosecutors don't have to abide by those wishes because they represent the people as a whole, not the victims, but they will take victim families into account.

"They always consider it," said Mr. Harris. "They're not, frankly, controlled by it."

The federal prosecution of Dylann Roof is probably the closest parallel to Mr. Bowers' case.

Roof, a white supremacist, was sentenced to death last year for the hate-driven killing of nine parishioners at a black church in Charleston, S.C., in 2015. But the families of his victims have said they do not want him to be executed because of their Christian beliefs.

Mr. Harris said it's too early to know whether the same dynamic will play out with Mr. Bowers' Jewish victims.

It's hard to predict how long it will take for Mr. Bowers to go to trial or if he goes to trial at all. The vast majority of federal defendants, about 95 percent, plead guilty.

Even if he is convicted and sentenced to death, however, the appeals process is likely to take years. State death penalty cases afford defendants a double layer of appeals, in which an inmate first exhausts state appeals and then starts the process again in the federal courts through a habeas petition.

The federal system is less complex because there is no state involvement and because Congress and the Supreme Court have been trying to streamline the process. Two years after the Oklahoma City bombing, for example, President Clinton signed the Anti-Terrorism and Effective Death Penalty Act, which covers both state and federal prisoners. It established stricter filing deadlines, limited evidentiary hearings and allowed a prisoner to file only a single habeas petition.

Despite those measures, appeals still take time as inmates pursue any number of arguments, from ineffective counsel to prosecutorial misconduct. And sometimes those claims are validated.

"The gears of the justice system turn slowly, and this is not entirely inappropriate," Mr. Harris said. "This is something you want to get right. You're talking about the state [or federal government] taking someone's life."

Support for the death penalty has been dropping for decades. Slightly less than half of Americans now support it, down from 80 percent in the mid-1990s. Former President Barack Obama called the practice "deeply troubling."

While most people are familiar with the death penalty as it applies in state homicide cases, there are about 60 federal crimes that also provide for the death penalty, such as murder for hire, murder during a kidnapping or murder committed during a drug-trafficking crime.

In Mr. Bowers' case, the charges include obstruction of exercise of religious beliefs resulting in death and use of a gun to commit murder during a crime of violence.

Use of the death penalty is authorized by the Justice Department in consultation with the local U.S. attorney's office. Almost all federal prisoners on death row - 62 as of this week - are housed at Terre Haute. Many states have just one or two defendants on federal death row. Texas has the most by far with 13. Pennsylvania has one.

The state has many people on death row in its prisons but, like the federal government, hasn't executed anyone in decades. The last executions were in the 1990s.

First Published: October 31, 2018, 11:00 a.m.